Abstract

Perioperative pain management has shifted from standardized, procedure-based protocols toward individualized, patient-centered approaches. Inadequate pain control can result in short-term adverse outcomes, including delayed ambulation, prolonged hospitalization, and increased complications, as well as long-term sequelae such as chronic persistent postsurgical pain. Early models of preemptive and preventive analgesia emphasized pain relief primarily through the use of opioids. Growing concern about opioid-related adverse effects established the basis for multimodal and opioid-sparing strategies. Nevertheless, with the onset of the global opioid crisis, heightened awareness of the risks of opioid overuse has fueled interest in opioid-free techniques. However, evidence does not demonstrate that opioid-free methods are superior to opioid-sparing approaches. This underscores the importance of returning to the central goals of enhanced recovery after surgery: early restoration of function and reduction of complications. Within this framework, personalized pain management has emerged as a practical paradigm that tailors interventions to individual characteristics, including comorbidities, psychological status, pain sensitivity, and recovery objectives. This review outlines the rationale, current practices, and future directions of personalized perioperative pain management and proposes a framework for integrating new strategies into clinical care.

-

Keywords: Analgesia; Enhanced recovery after surgery; Pain management; Personalized medicine

Introduction

Background

Over the past decade, surgical trends have evolved significantly, ranging from major inpatient operations to minimally invasive techniques and an increasing number of day care surgeries [

1]. These developments have improved surgical efficiency, shortened hospital stays, and broadened treatment options for diverse patient populations. At the same time, they have intensified the need for more advanced perioperative pain management strategies [

2].

Pain characteristics, including intensity and duration, vary considerably depending on the type and invasiveness of surgery. Day care procedures in particular demand careful attention, as inadequate analgesia can delay discharge, hinder early mobilization, lower patient satisfaction, and increase the likelihood of readmission. More broadly, poorly controlled perioperative pain compromises respiratory function, restricts ambulation, amplifies physiological stress responses, and raises the risk of long-term complications such as delayed psychological recovery and the development of chronic persistent postsurgical pain (CPSP) [

3,

4].

These changes in surgical practice highlight the limitations of standardized, procedure-based analgesic regimens. Uniform protocols often fail to incorporate key determinants of pain experience, including individual pain sensitivity, baseline functional status, comorbidities, and recovery goals. As minimally invasive techniques, enhanced recovery pathways, and the continued expansion of outpatient operations become more common, recognition of the importance of personalized perioperative pain management is growing.

This patient-centered approach adapts analgesic strategies to individual needs, surgical characteristics, and expected recovery trajectories. Recent studies indicate that individualized pain assessment combined with multimodal interventions reduces postoperative pain severity, lowers opioid consumption, and shortens hospital stays [

5,

6]. At the same time, advances in pharmacogenomics hold promise for guiding analgesic choice and dosing based on genetic profiles, thereby improving efficacy while limiting adverse effects.

The aim of this narrative review is to present the rationale, current practices, and emerging directions in personalized perioperative pain management, and to explore strategies for translating these concepts into effective clinical protocols.

Ethics statement

As this study is a narrative review, it did not require institutional review board approval or individual consent.

Historical evolution of perioperative pain management

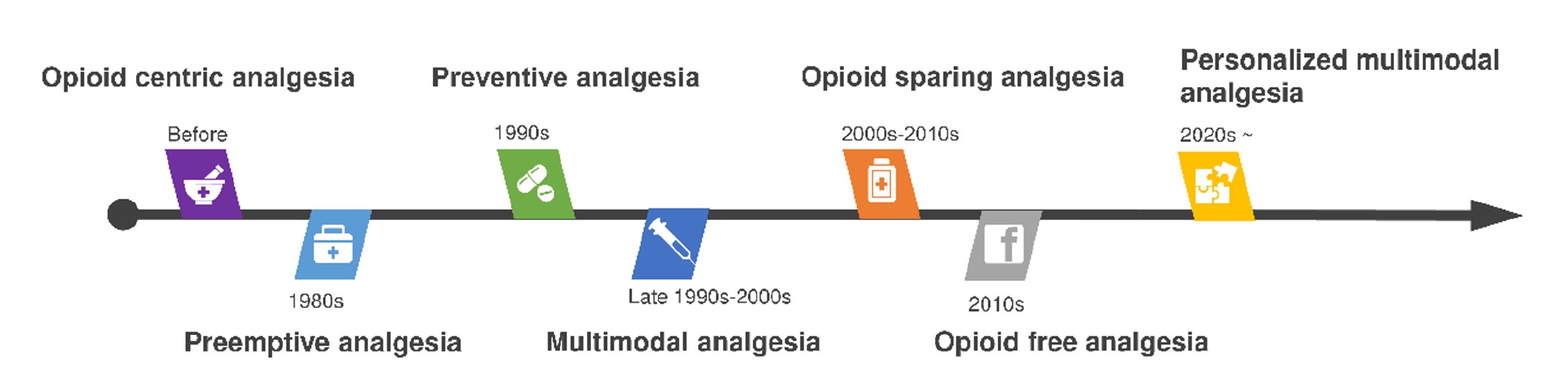

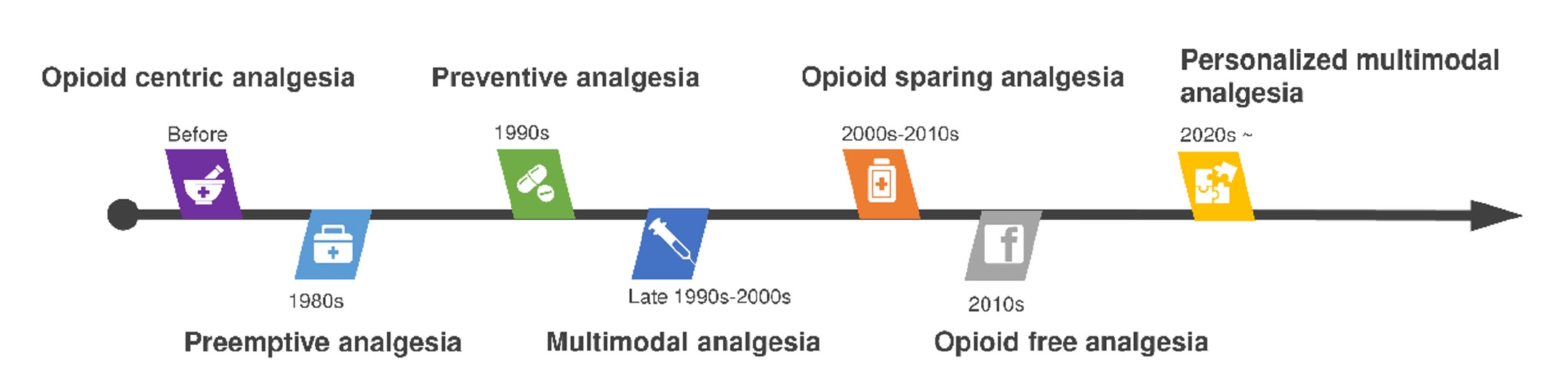

The conceptual framework of perioperative pain management has undergone profound transformation over the past 4 decades (

Fig. 1). Each period has been shaped by new insights into pain physiology, evolving clinical practices, and broader societal forces.

A major conceptual advance occurred in the 1980s when Clifford Woolf introduced the idea of preemptive analgesia. His work demonstrated that surgical injury could trigger central sensitization, a process in which repeated or sustained noxious input amplifies pain signaling in the central nervous system [

7,

8]. Based on this mechanism, it was hypothesized that administering analgesic interventions before surgical incision could attenuate sensitization and thereby reduce postoperative pain. Although groundbreaking, clinical trials yielded inconsistent results, in part because preemptive analgesia focused narrowly on the timing of drug administration without ensuring continuous pain control throughout the perioperative period.

In the 1990s, the concept of preventive analgesia emerged. Unlike strategies confined to the pre-incision phase, preventive analgesia sought to maintain continuous suppression of nociceptive input throughout the entire perioperative period [

9,

10]. This broader approach addressed the shortcomings of strictly preemptive methods and laid the foundation for more integrated, multimodal strategies.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the principle of multimodal analgesia had become well established. This approach emphasized combining multiple classes of pharmacologic agents with regional anesthesia techniques to achieve additive or synergistic effects while reducing reliance on any single drug [

11]. Typical combinations included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol, gabapentinoids, local anesthetics, and, in selected cases, low-dose opioids. Multimodal analgesia represented a paradigm shift away from opioid-dominant regimens toward individualized combinations designed to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects.

During the 2000s and 2010s, opioid-sparing strategies gained momentum, largely driven by the global adoption of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs [

12]. These pathways promoted early mobilization, reduced hospital stays, and decreased complication rates, all supported by minimizing opioid use. The rationale was twofold: (1) to accelerate recovery by reducing opioid-related adverse events such as nausea, sedation, and ileus, and (2) to mitigate the growing public health threat of opioid misuse and dependence.

In parallel, the early 2000s saw a dramatic escalation in oral opioid prescribing in the United States, fueled by aggressive pharmaceutical marketing, permissive prescribing practices, and supportive policy frameworks [

13,

14]. Excessive postoperative prescriptions were often issued without consideration of surgical invasiveness or actual pain severity, leading to widespread availability of unused medications [

15,

16]. At the same time, socioeconomic stressors such as rising unemployment exacerbated misuse, and opioid overdose deaths increased by more than 180% during this period [

14,

17].

Heightened concern over misuse and dependence reframed the epidemic as both a public health and social crisis. In this context, opioid-free analgesia (OFA) emerged, aiming to eliminate opioids by substituting agents such as dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and intravenous lidocaine [

18,

19]. Despite its appeal during the opioid epidemic, OFA has not achieved broad clinical adoption because supporting evidence remains limited, protocols are inconsistent, and questions regarding safety and efficacy persist [

17,

20,

21].

In sum, the historical trajectory of perioperative pain management reflects a progressive departure from opioid-centered strategies toward integrated, multimodal, and increasingly individualized approaches. These developments have laid the foundation for the current paradigm of personalized perioperative pain management.

The advent of personalized pain management

Concerns about opioid overuse have been heightened not only by the clinical adverse effects of opioids—including over-sedation, respiratory depression, tolerance, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia—but also by the wider societal consequences of the opioid crisis. In this context, OFA has drawn increasing attention. However, current evidence does not demonstrate clear superiority of OFA over opioid-sparing strategies in either analgesic efficacy or reduction of excessive prescribing [

17]. Accordingly, rather than focusing exclusively on eliminating opioids, it is more appropriate to return to the central aim of ERAS: restoring patients to baseline functional status as rapidly as possible while minimizing perioperative complications.

Personalized perioperative pain management has therefore emerged as a pragmatic, patient-centered strategy. Instead of framing the debate as opioid versus non-opioid, this approach emphasizes tailoring the analgesic plan to each patient’s individual characteristics, the surgical context, and specific recovery goals [

22-

25].

Pain perception and treatment response are influenced by many factors. These include demographic variables (such as age and sex), comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain conditions), baseline functional capacity, and psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, and catastrophizing tendencies. Biological and genetic variability, differences in pain sensitivity, and circadian rhythms also shape analgesic requirements and outcomes [

25-

29].

The overarching aim of personalized perioperative pain management is to provide effective analgesia while preserving functional capacity, reducing adverse drug effects, and promoting early mobilization and recovery. This is achieved through a combination of multimodal analgesia, advanced regional anesthesia techniques, and technology-enabled monitoring tools, including wearable sensors and digital pain assessment platforms [

27,

30,

31].

This approach aligns closely with the broader objectives of ERAS protocols. Beyond promoting rapid recovery, it seeks to improve long-term functional outcomes and quality of life. Perioperative pain management must therefore extend its scope beyond the immediate postoperative period to include the prevention of CPSP. CPSP can have lasting consequences, including physical disability, psychological distress, and reduced social participation [

32,

33]. Consequently, early recognition of patient- and procedure-specific risk factors is essential for developing individualized preventive strategies (

Table 1).

Multimodal approach for personalized pain management

A multimodal approach forms the cornerstone of personalized perioperative pain management, integrating pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, regional anesthesia, and technology-based strategies in a phase- and risk-specific manner. Patients with preoperative risk factors such as chronic pain, prolonged opioid exposure, or psychological comorbidities benefit from early multidisciplinary consultation. Such consultation can optimize analgesic planning, provide psychological support, and, when appropriate, initiate prehabilitation to enhance resilience and postoperative outcomes. For surgeries with high anticipated nociceptive input, regional anesthesia techniques—including epidural analgesia, peripheral nerve blocks, and fascial plane blocks—can reduce central sensitization, limit intraoperative opioid use, and facilitate recovery. In the postoperative phase, clinicians must escalate therapy promptly in patients with severe acute pain or neuropathic features, using targeted pharmacologic agents, repeat or rescue nerve blocks, and adjuvant medications that address neuropathic pain. Organizing multimodal strategies within this phase-specific framework helps translate personalized pain management into evidence-based practice, improving acute pain control, accelerating recovery, and enhancing long-term quality of life.

Pharmacological approach

Pharmacological strategies in personalized perioperative pain management center on multimodal analgesia: combining agents with complementary mechanisms to achieve additive or synergistic pain relief while limiting opioid use. Non-opioid agents—acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and gabapentinoids—serve as the foundation and should be selected and dosed based on comorbidities, renal and hepatic function, and the expected pain phenotype (somatic, visceral, or neuropathic) [

23]. In patients at high risk of respiratory complications (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity hypoventilation), opioid-sparing regimens should be prioritized, reserving only short courses of the lowest effective opioid doses when unavoidable. In renal dysfunction, nephrotoxic agents—especially NSAIDs—should be avoided, and renally cleared drugs such as gabapentinoids should be dose-adjusted or substituted [

24,

34]. In hepatic impairment and older adults, therapy should begin with lower doses and be titrated cautiously, accounting for altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, as well as heightened susceptibility to sedation, delirium, and hypotension [

35,

36]. For patients with neuropathic features or a high risk of CPSP, mechanism-based adjuvants—such as NMDA-receptor antagonists (e.g., low-dose ketamine), gabapentinoids, and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors—should be integrated into structured, time-limited protocols with clear goals and monitoring for side effects such as dizziness, somnolence, and hemodynamic instability [

27,

37].

Pharmacogenomics provides another dimension of personalization.

CYP2D6 polymorphisms affect bioactivation of codeine and tramadol, producing poor or ultrarapid metabolizer phenotypes that result in either loss of efficacy or increased toxicity [

23,

38]. Variants in

OPRM1 (μ-opioid receptor) influence opioid sensitivity, while

COMT and

ABCB1 polymorphisms may further contribute to variability in analgesic response and central nervous system exposure [

39,

40]. Although not yet routine, targeted pharmacogenomic testing can inform drug selection and dosing in specific scenarios, reducing variability and minimizing adverse outcomes.

Emerging evidence also highlights the role of circadian biology in modulating nociception and analgesic response. Diurnal variations in pain thresholds and time-dependent differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (chronopharmacology) have been observed for several analgesics [

28,

41,

42]. Incorporating timing into perioperative regimens—such as aligning scheduled non-opioids with periods of heightened pain or activity and avoiding sedative loading during nocturnal vulnerability—may optimize efficacy and reduce side effects [

43].

Together, these biological determinants—clinical phenotype, organ function, pharmacogenomic variability, and circadian rhythms—support moving beyond “one-size-fits-all” multimodal regimens toward more precise, patient-specific pharmacological strategies. Integrating these factors with established perioperative principles advances effective analgesia, preserves function, accelerates recovery, and reduces variability and adverse outcomes.

Regional anesthesia

Regional anesthesia, which provides targeted analgesia by blocking nociceptive transmission, is a central component of personalized perioperative pain management. Advances in imaging, particularly the widespread adoption of ultrasound guidance, have transformed regional anesthesia from landmark-based blocks to more precise peripheral nerve and fascial plane techniques. These advances allow clinicians to deliver effective analgesia while avoiding complications traditionally associated with neuraxial approaches, such as hypotension, urinary retention, or unnecessary motor impairment.

In thoracic surgery, analgesic strategies must be adapted to the degree of invasiveness. Thoracotomy produces severe acute pain and is a risk factor for CPSP, making potent analgesia essential. Thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) has long been regarded as the gold standard, providing excellent static and dynamic pain control with substantial opioid-sparing benefits, though its use may be constrained by adverse effects such as hypotension or urinary retention. Thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB) has emerged as an effective alternative, producing unilateral somatic and sympathetic blockade with comparable efficacy to TEA but a more favorable safety profile. Although intercostal nerve block (ICNB) offers better analgesia than systemic opioids, its short duration limits its role as a primary modality [

44,

45].

In contrast, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is less invasive, and postoperative pain is less intense than after thoracotomy. In this context, TPVB may provide non-inferior analgesia compared with TEA while avoiding neuraxial risks [

45]. The erector spinae plane block (ESPB) has gained popularity due to its technical simplicity, wide dermatomal coverage, and favorable safety profile. Similarly, the serratus anterior plane block is particularly effective for VATS, lateral chest wall, and breast surgery [

46]. ICNB remains widely used and reduces both intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption, but its relatively short duration and potential systemic toxicity when administered at multiple levels restrict its role as a stand-alone technique. The development of liposomal bupivacaine has renewed interest in ICNB by potentially prolonging its effects, though current evidence is inconsistent, with some studies demonstrating improved analgesia and others finding no advantage over conventional agents [

45]. As a result, ICNB in VATS is increasingly regarded as an element of multimodal analgesia rather than a sole technique.

Personalized regional anesthesia also emphasizes motor-sparing and risk-adapted techniques. For example, the adductor canal block in knee surgery provides effective analgesia while preserving quadriceps strength, enabling early mobilization and rehabilitation, and is now frequently favored over femoral nerve block in this setting [

22,

33]. In patients at high risk of respiratory depression, effective shoulder analgesia can be achieved while reducing phrenic nerve involvement through newer approaches such as selective upper trunk block or combined suprascapular and axillary nerve blocks, rather than traditional interscalene block [

47].

By tailoring block selection to surgical invasiveness, expected pain patterns, and patient-specific risk factors, clinicians can enhance analgesic efficacy, reduce opioid requirements, and support early ambulation. Regional anesthesia may also contribute to the prevention of CPSP by mitigating central sensitization. Thus, it exemplifies the principles of personalized pain management, integrating technological advances with individualized decision-making to improve both short- and long-term outcomes.

Technology-enabled monitoring

Recent advances in digital health technologies have expanded opportunities for personalized pain monitoring and management. Smartphone applications for acute pain services allow real-time reporting of pain scores, medication use, and side effects, enabling clinicians to respond promptly and adjust treatment regimens in patient-specific ways [

48]. Wearable devices that measure physiologic parameters such as heart rate variability, skin conductance, or movement patterns provide continuous, objective data that complement traditional subjective pain scores. Furthermore, high-resolution perioperative datasets such as VitalDB and the MOVER (Medical Informatics Operating Room Vitals and Events Repository) create a foundation for AI-driven predictive analytics. These systems can anticipate analgesic requirements, identify patients at risk of inadequate pain control, and support real-time decision-making [

49,

50]. Emerging perspectives also suggest that artificial intelligence applied to large, heterogeneous datasets could help identify pain subtypes, predict treatment responses, and guide individualized strategies, further reinforcing the role of precision medicine in perioperative care [

5].

Although still in the early stages of adoption, these technologies illustrate the potential for integrating digital tools into routine perioperative management to achieve more consistent, patient-centered outcomes. Significant challenges remain, including data standardization, integration into clinical workflows, and concerns over privacy and security. Nevertheless, technology-enabled monitoring represents a promising frontier in personalized perioperative pain management. By bridging the gap between conventional clinical assessment and precision medicine, digital tools may help establish the next generation of individualized pain strategies. The integration of pharmacological approaches, regional anesthesia, and digital health innovations highlights how personalized models can reshape perioperative pain management, and future research should lay the foundation for broader clinical application.

Conclusion

Perioperative pain management is shifting from standardized, procedure-based regimens to individualized, patient-centered strategies. Rather than concentrating exclusively on opioid-free concepts, improving patient outcomes should be prioritized through optimized multimodal pharmacological regimens, tailored regional anesthesia, and non-pharmacological interventions, all aligned with ERAS protocols. By considering patient-specific factors—such as comorbidities, psychological status, and functional goals—clinicians can reduce opioid dependence, facilitate early mobilization, and prevent CPSP. Clinical decision-making should not be guided merely by technical feasibility but should instead be anchored in patient-centered values, with functional recovery and patient satisfaction as primary goals. Ultimately, the safe and efficient restoration of preoperative functional status, while minimizing complications and improving quality of life, represents the highest objective of perioperative pain management.

-

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: MKK, HK. Data curation: MKK, HK. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: MKK, HK. Project administration: MKK, HK. Writing–original draft: MKK. Writing–review & editing: MKK, HK.

-

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Pain management concepts.

Table 1.Reported risk factors for chronic persistent postsurgical pain

|

Category |

Risk factors |

|

Preoperative |

Pre-existing painful condition; long-term opioid use; psychological comorbidities (e.g., depression, anxiety); young adult age; female sex; high body mass index (>30 kg/m2) |

|

Surgical |

Type of surgery (e.g., thoracotomy, amputation, mastectomy) |

|

Postoperative |

Severe acute postoperative pain; postoperative neuropathic pain |

References

- 1. Concannon ES, Hogan AM, Flood L, Khan W, Waldron R, Barry K. Day of surgery admission for the elective surgical in-patient: successful implementation of the Elective Surgery Programme. Ir J Med Sci 2013;182:127-133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-012-0850-5

- 2. Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, Carter T, Cassidy CL, Chittenden EH, Degenhardt E, Griffith S, Manworren R, McCarberg B, Montgomery R, Murphy J, Perkal MF, Suresh S, Sluka K, Strassels S, Thirlby R, Viscusi E, Walco GA, Warner L, Weisman SJ, Wu CL. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain 2016;17:131-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008

- 3. Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2005;23:21-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.013

- 4. Wu CL, Naqibuddin M, Rowlingson AJ, Lietman SA, Jermyn RM, Fleisher LA. The effect of pain on health-related quality of life in the immediate postoperative period. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1078-1085. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000081722.09164.D5

- 5. Casarin S, Haelterman NA, Machol K. Transforming personalized chronic pain management with artificial intelligence: a commentary on the current landscape and future directions. Exp Neurol 2024;382:114980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114980

- 6. Chen Q, Chen E, Qian X. A narrative review on perioperative pain management strategies in enhanced recovery pathways: the past, present and future. J Clin Med 2021;10:2568. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10122568

- 7. Kang S, Brennan TJ. Mechanisms of postoperative pain. Anesth Pain Med 2016;11:236-248. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2016.11.3.236

- 8. Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature 1983;306:686-688. https://doi.org/10.1038/306686a0

- 9. Kissin I. Preemptive analgesia: terminology and clinical relevance. Anesth Analg 1994;79:809-810.

- 10. Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Zahn PK. From preemptive to preventive analgesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2006;19:551-555. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aco.0000245283.45529.f9

- 11. Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg 1993;77:1048-1056. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199311000-00030

- 12. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00866-8

- 13. Maclean JC, Mallatt J, Ruhm CJ, Simon K. The opioid crisis, health, healthcare, and crime: a review of quasi-experimental economic studies. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 2022;703:15-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162221149285

- 14. Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020;(356):1-8.

- 15. Wunsch H, Wijeysundera DN, Passarella MA, Neuman MD. Opioids prescribed after low-risk surgical procedures in the United States, 2004-2012. JAMA 2016;315:1654-1657. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0130

- 16. Neuman MD, Bateman BT, Wunsch H. Inappropriate opioid prescription after surgery. Lancet 2019;393:1547-1557. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30428-3

- 17. Kharasch ED, Clark JD. Opioid-free anesthesia: time to regain our balance. Anesthesiology 2021;134:509-514. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003705

- 18. Forget P. Opioid-free anaesthesia: why and how?: a contextual analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2019;38:169-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2018.05.002

- 19. Patvardhan C, Ferrante M. Opiate free anaesthesia and future of thoracic surgery anaesthesia. J Vis Surg 2018;4:253. https://doi.org/10.21037/jovs.2018.12.08

- 20. Mayoral Rojals V, Charaja M, De Leon Casasola O, Montero A, Narvaez Tamayo MA, Varrassi G. New insights into the pharmacological management of postoperative pain: a narrative review. Cureus 2022;14:e23037. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.23037

- 21. De Cassai A, Geraldini F, Tulgar S, Ahiskalioglu A, Mariano ER, Dost B, Fusco P, Petroni GM, Costa F, Navalesi P. Opioid-free anesthesia in oncologic surgery: the rules of the game. J Anesth Analg Crit Care 2022;2:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44158-022-00037-8

- 22. Goel S, Deshpande SV, Jadawala VH, Suneja A, Singh R. A comprehensive review of postoperative analgesics used in orthopedic practice. Cureus 2023;15:e48750. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.48750

- 23. Hosseinzadeh F, Nourazarian A. Biochemical strategies for opioid-sparing pain management in the operating room. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025;41:101927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2025.101927

- 24. Joachim MV, Miloro M. Multimodal approaches to postoperative pain management in orthognathic surgery: a comprehensive review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2025;54:914-923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2025.02.004

- 25. Komasawa N. Revitalizing postoperative pain management in enhanced recovery after surgery via inter-departmental collaboration toward precision medicine: a narrative review. Cureus 2024;16:e59031. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59031

- 26. Dickerson DM, Mariano ER, Szokol JW, Harned M, Clark RM, Mueller JT, Shilling AM, Udoji MA, Mukkamala SB, Doan L, Wyatt KE, Schwalb JM, Elkassabany NM, Eloy JD, Beck SL, Wiechmann L, Chiao F, Halle SG, Krishnan DG, Cramer JD, Ali Sakr Esa W, Muse IO, Baratta J, Rosenquist R, Gulur P, Shah S, Kohan L, Robles J, Schwenk ES, Allen BF, Yang S, Hadeed JG, Schwartz G, Englesbe MJ, Sprintz M, Urish KL, Walton A, Keith L, Buvanendran A. Multiorganizational consensus to define guiding principles for perioperative pain management in patients with chronic pain, preoperative opioid tolerance, or substance use disorder. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2024;49:716-724. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2023-104435

- 27. Rosenberger DC, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Chronic post-surgical pain - update on incidence, risk factors and preventive treatment options. BJA Educ 2022;22:190-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2021.11.008

- 28. Cicekci F, Sargin M, Siki FO. How does circadian rhythm affect postoperative pain after pediatric acute appendicitis surgery? Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:125-133. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23038

- 29. Verdiner R, Khurmi N, Choukalas C, Erickson C, Poterack K. Does adding muscle relaxant make post-operative pain better?: a narrative review of the literature from US and European studies. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2023;18:340-348. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23055

- 30. Ryu G, Choi JM, Seok HS, Lee J, Lee EK, Shin H, Choi BM. Machine learning based quantitative pain assessment for the perioperative period. NPJ Digit Med 2025;8:53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01362-8

- 31. Speed TJ, Hanna MN, Xie A. The personalized pain program: a new transitional perioperative pain care delivery model to improve surgical recovery and address the opioid crisis. Qual Manag Health Care 2024;33:61-63. https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0000000000000450

- 32. Humble SR, Varela N, Jayaweera A, Bhaskar A. Chronic postsurgical pain and cancer: the catch of surviving the unsurvivable. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2018;12:118-123. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000341

- 33. Chitnis SS, Tang R, Mariano ER. The role of regional analgesia in personalized postoperative pain management. Korean J Anesthesiol 2020;73:363-371. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.20323

- 34. Kanchanasurakit S, Arsu A, Siriplabpla W, Duangjai A, Saokaew S. Acetaminophen use and risk of renal impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2020;39:81-92. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.19.106

- 35. Pickering G, Kotlinska-Lemieszek A, Krcevski Skvarc N, O’Mahony D, Monacelli F, Knaggs R, Morel V, Kocot-Kepska M. Pharmacological pain treatment in older persons. Drugs Aging 2024;41:959-976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01151-8

- 36. Majid M, Yahya M, Ansah Owusu F, Bano S, Tariq T, Habib I, Kumar B, Kashif M, Varrassi G, Khatri M, Kumar S, Iqbal A, Khan AS. Challenges and opportunities in developing tailored pain management strategies for liver patients. Cureus 2023;15:e50633. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.50633

- 37. Carley ME, Chaparro LE, Choiniere M, Kehlet H, Moore RA, Van Den Kerkhof E, Gilron I. Pharmacotherapy for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery in adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2021;135:304-325. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003837

- 38. Ferreira do Couto ML, Fonseca S, Pozza DH. Pharmacogenetic approaches in personalized medicine for postoperative pain management. Biomedicines 2024;12:729. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12040729

- 39. Dzierba AL, Stollings JL, Devlin JW. A pharmacogenetic precision medicine approach to analgesia and sedation optimization in critically ill adults. Pharmacotherapy 2023;43:1154-1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2768

- 40. Crews KR, Monte AA, Huddart R, Caudle KE, Kharasch ED, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, Leeder JS, Callaghan JT, Samer CF, Klein TE, Haidar CE, Van Driest SL, Ruano G, Sangkuhl K, Cavallari LH, Muller DJ, Prows CA, Nagy M, Somogyi AA, Skaar TC. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for CYP2D6, OPRM1, and COMT genotypes and select opioid therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;110:888-896. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2149

- 41. Sandoval R, Boniface DR, Stricker R, Cregg R. Circadian variation of pain as a measure of the analgesia requirements during the first 24-postoperative hours in patients using an opioid patient controlled analgesia delivery system. J Curr Med Res Opin 2018;1:1-10. https://doi.org/10.15520/jcmro.v1i2.13

- 42. Boom M, Grefkens J, van Dorp E, Olofsen E, Lourenssen G, Aarts L, Dahan A, Sarton E. Opioid chronopharmacology: influence of timing of infusion on fentanyl’s analgesic efficacy in healthy human volunteers. J Pain Res 2010;3:183-190. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S13616

- 43. Kaskal M, Sevim M, Ulker G, Keles C, Bebitoglu BT. The clinical impact of chronopharmacology on current medicine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2025;398:6179-6191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-025-03788-7

- 44. Kim BR, Yoon SH, Lee HJ. Practical strategies for the prevention and management of chronic postsurgical pain. Korean J Pain 2023;36:149-162. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.23080

- 45. Hamilton C, Alfille P, Mountjoy J, Bao X. Regional anesthesia and acute perioperative pain management in thoracic surgery: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis 2022;14:2276-2296. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-1740

- 46. Wittayapairoj A, Sinthuchao N, Somintara O, Thincheelong V, Somdee W. A randomized double-blind controlled study comparing erector spinae plane block and thoracic paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia after breast surgery. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2022;17:445-453. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.22157

- 47. Kang R, Ko JS. Recent updates on interscalene brachial plexus block for shoulder surgery. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2023;18:5-10. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.22254

- 48. Yoon SH, Yoon S, Jeong DS, Lee M, Lee E, Cho YJ, Lee HJ. A smart device application for acute pain service in surgical patients at a tertiary hospital in South Korea: a prospective observational feasibility study. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:216-226. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.24059

- 49. Lim L, Lee HC. Open datasets in perioperative medicine: a narrative review. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2023;18:213-219. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23076

- 50. Antel R, Whitelaw S, Gore G, Ingelmo P. Moving towards the use of artificial intelligence in pain management. Eur J Pain 2025;29:e4748. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.4748