Is the criminal prosecution of physicians in Korea excessive?

Recently, a Korean government report—commissioned by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) and conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs—examined the criminal prosecution of physicians in Korea [

1]. On average, 38 criminal trials took place annually.

Korea’s 38 cases: among the highest global rates of criminal trials

This figure is striking. Even acknowledging the research limitations and the report’s scope, the finding that 38 physicians are criminally prosecuted each year for adverse medical outcomes is significant. A straightforward international comparison suggests that, in a country with about 100,000 practicing physicians, 38 prosecutions annually for medical-related incidents places Korea among the highest in the world. For example, although the data are older, one review indicated that the province of Ontario, Canada, recorded only one case in 108 years in which a physician was criminally convicted for a medical incident—an anesthesiologist who self-reported leaving their post, resulting in a medical accident [

2]. Apart from this case, there are no verifiable instances of criminal prosecution for medical-related incidents in Ontario.

Table 1 compares outcomes of first-instance criminal trials for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury among physicians in Korea—based on a complete enumeration by the Korean Medical Association Research Institute for Healthcare Policy (RIHP)—with those in Japan and the United Kingdom. Between 1999 and 2016 (18 years), Japan recorded 202 first-instance criminal judgments against physicians for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury, of which only 32 resulted in convictions—an average of 1.8 per year. Moreover, Japan’s scope included the management and supervision of medical assistants as well as the operation of medical equipment, suggesting that the number of cases involving purely medical malpractice is likely smaller. In Commonwealth and Nordic countries—often highlighted as examples of robust public healthcare systems—criminal prosecutions of physicians are so rare that official statistics are almost nonexistent. A fairly recent UK judiciary report recorded only 4 physician convictions over a 6-year period [

3,

4].

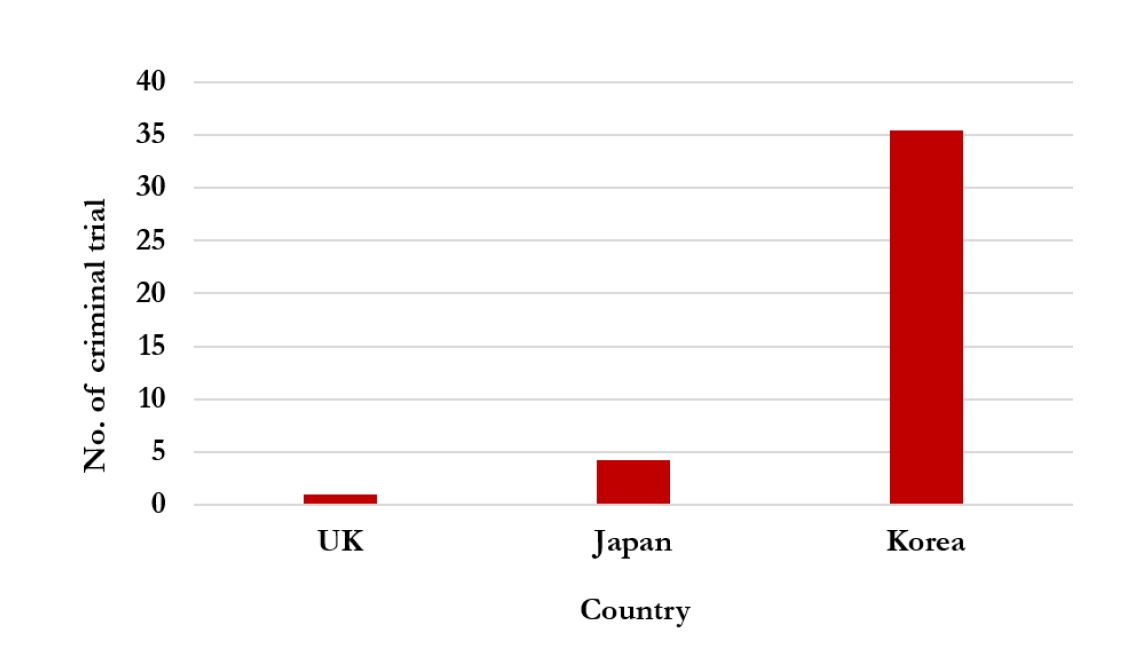

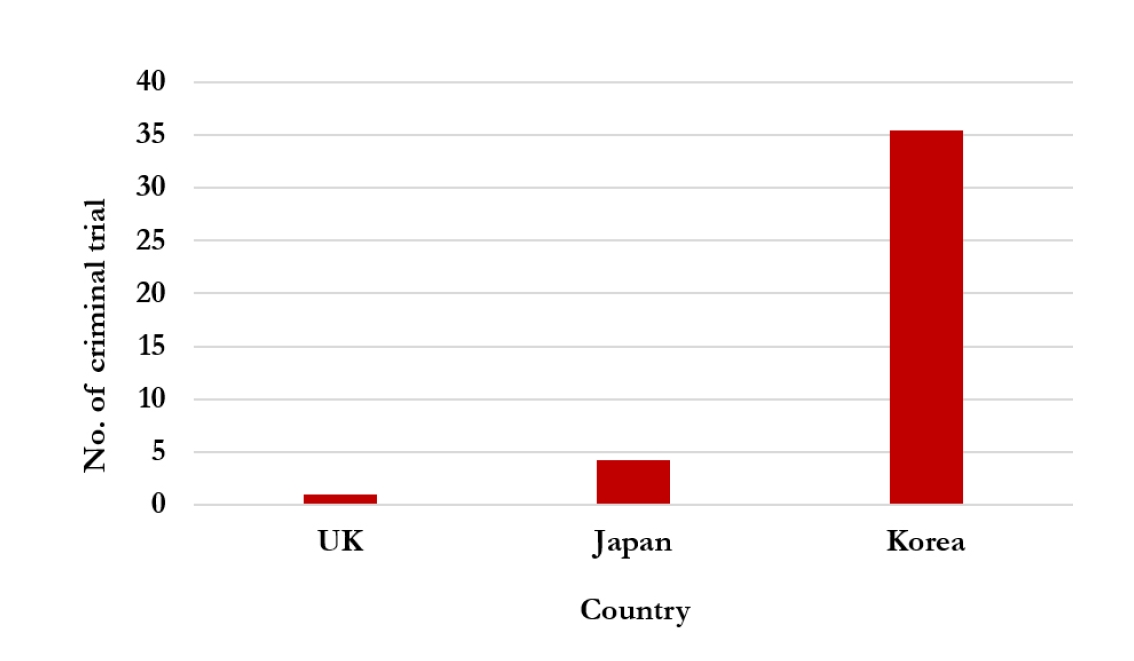

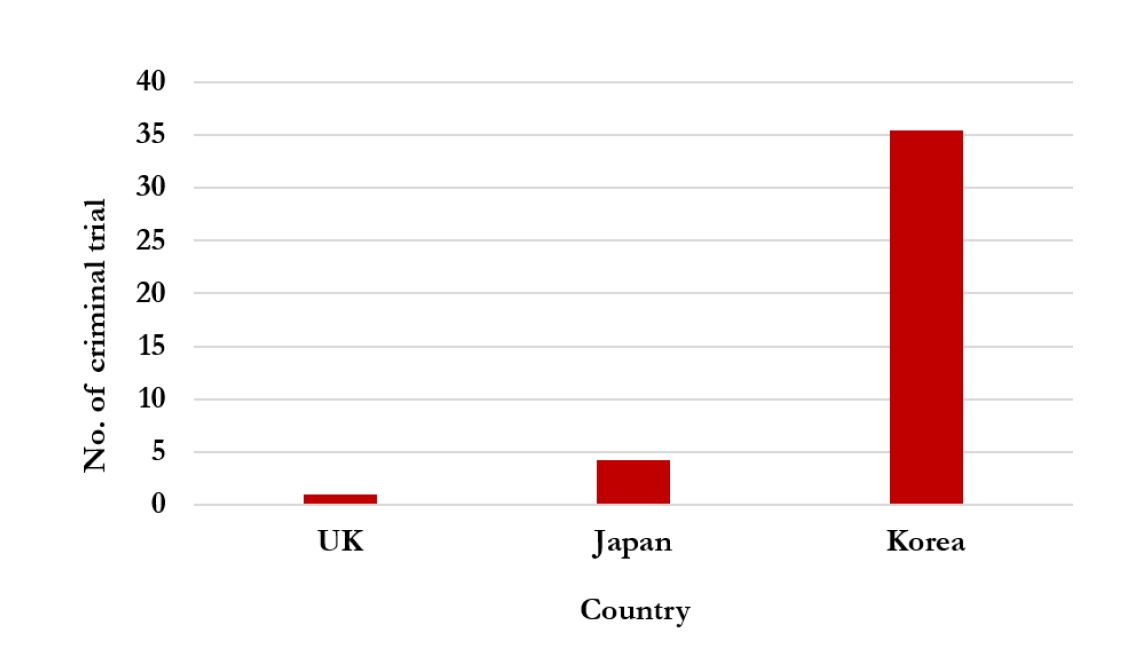

Fig. 1 presents the relative average number of criminal trials for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury by physicians, normalized to the United Kingdom as 1.

Differences in legal systems are not a sufficient explanation

Explanations that attribute Korea’s high incidence of criminal prosecutions in medical cases to differences in legal tradition—namely, the distinction between its continental legal system and the Anglo-American common law system—are inadequate when tested against empirical evidence from other civil-law jurisdictions. In Germany, criminal prosecutions of physicians for medical malpractice are exceptionally rare. France, despite its reputation for a comparatively stringent criminal liability framework, has an annual average of only 10–13 cases [

5]. Notably, these figures encompass a broad range of criminal offenses, including violence, rape, and sexual assault, rather than being limited to medical negligence. A peer-reviewed and widely cited international study further reveals that prosecutions directly attributable to medical practice account for less than half of such totals. Corroborating this, a review of expert opinions submitted to prosecutors by the Bonn Institute of Forensic Medicine—which has jurisdiction over the state of Nordrhein–Westphalia—between 1989 and 2003 (a span of 15 years) found only one instance in which a physician was convicted of negligent manslaughter. Notably, even that case involved additional criminal conduct beyond the scope of medical negligence [

6]. Overall, these findings indicate that differences in legal tradition cannot fully account for the markedly higher rates of criminal prosecution observed in Korea’s medical sector.

Adjusted for population, Korea’s criminal prosecution rate for medical practice is up to 60 times higher than those of France, the United Kingdom, and Germany

Even in France—with its relatively high rate of criminal prosecution for medical incidents compared to other developed nations—the number of cases directly involving medical practice is about 5–6 annually, with most resulting in suspended sentences or fines. On rare occasions, prison sentences of 7–10 years have been imposed for crimes such as rape and assault [

5]. When Korea’s 38 cases per 100,000 active physicians are compared to France’s minimum of 200,000 physicians, the difference is stark: Korea’s rate is over 10 times higher than that of France and at least 60 times higher than the rates in the United Kingdom and Germany. This is a striking contradiction; one would not expect a nation that prides itself on having a world-class healthcare system and highly skilled medical professionals to lead the world in criminal prosecutions of physicians. In the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, legal proceedings for medical incidents are handled under tort law, which prioritizes pre-trial mediation and resorts to criminal law only in exceptional cases. These countries maintain stable systems for compensating medical accidents and handling inevitable adverse outcomes. By contrast, Korea’s inadequate compensation framework raises concerns that criminal prosecution may be used to pressure physicians, thus casting doubt on the fairness of the legal process. Whether this stems from differences in legal education, professional standards, or institutional culture, international comparisons suggest that Korea’s judicial approach remains difficult for the medical community to accept.

Who will treat patients if misunderstandings about medical uncertainty turn physicians into criminals?

Even now, obtaining accurate data remains challenging and complex. Any research on this topic inevitably involves considerable estimation. If the likelihood of criminal prosecution in Korea is 10 to 60 times higher than in some other countries, a pressing question arises: Who would willingly become a physician, knowing they might face a criminal record simply for practicing medicine? Accordingly, this possibility of excessive criminal punishment may pose a serious threat to future physicians’ career choices.

Table 2 compares the outcomes of all first-instance criminal trials involving charges of occupational negligence resulting in death or injury, using 2014–2018 data from the RIHP and 2019–2023 data from the MOHW [

4].

The period covered by the Ministry’s investigation—marked by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and heightened disputes between the medical profession and the government—was characterized by unprecedented instability in the healthcare sector. Compared with the preceding 5 years, the number of physicians tried for medical negligence at the first-instance level increased by 19 and convictions rose by 18, while acquittals remained largely unchanged. These findings provide empirical evidence that both the incidence of criminal trials and conviction rates have increased in parallel with the structural instability of the medical field.

With nearly 700 apprehensions annually, will “medical deserts” worsen?

Even now, accurate statistics for comprehensive cases remain elusive. In a statistical report from the Public Prosecutors’ Office, “Crime analysis,” the category of “professionals” includes physicians alongside 6 other professional occupations and “other professionals.” These statistics are compiled under the heading “occupation of offenders”—a misnomer, as the data include suspects regardless of conviction—rather than “defendants.”

Tables 3 and

4 present Prosecutors’ Office data on cases involving professionals and physicians charged with occupational negligence resulting in death or injury [

7]. However, no statistical data are available regarding whether these individuals were formally indicted and brought to trial. Of note, the MOHW’s analysis indicates that the number of cases handled by the prosecution during 2019–2023 declined slightly compared with the preceding 5 years. This suggests that although the total number of cases involving physicians charged with occupational negligence resulting in death or injury has remained stable or decreased marginally, the number of first-instance criminal trials and convictions has increased—potentially indicating a shift toward stricter criminal accountability.

Unintended consequences of criminal punishment of medical practice

The fact that physicians in Korea are subjected to police investigations for actions performed in their medical practice is, when compared with other countries, difficult to regard as reasonable. It is difficult to overstate the shock and trauma these investigations inflict on professionals who have dedicated years of their lives to rigorous education and training. For many physicians, this experience leaves a permanent psychological scar. The situation of the Ewha Mokdong Hospital medical staff—who were imprisoned for months before being acquitted [

8]—illustrates the devastating personal and professional impact. Dismissing the possibility that excessive prosecution drives avoidance of essential specialties only obscures the unintended consequences of the criminal punishment of medical practice. The indiscriminate criminal prosecution of physicians reflects a dangerous indifference to the severe healthcare crisis currently unfolding in Korea.

Koreans, who have benefited from some of the highest levels of medical care in the world, must act to end these cruel punishments of physicians. Government officials and lawmakers should also work to resolve this tragic problem to safeguard the population’s health over the long term.

-

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: DSA. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: HSK. Project administration: DSA. Funding acquisition: not applicable. Writing–original draft: HSK, DSA. Writing–review & editing: HSK, DSA.

-

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Relative average number of criminal trials for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury by physicians, normalized to the United Kingdom as 1. From Kim HS, Lee JK, Kim KY. Current status and implications of the criminalization of medical practice [Internet]. Korean Medical Association, Research Institute for Healthcare Policy; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from:

https://rihp.re.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=research_report&wr_id=338 [

4].

Table 1.Criminal trial outcomes for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury

|

Korea, 2010–2020, 11 yr (average) |

Japan, 1999–2016, 18 yr (average) |

United Kingdom,2013–2018, 6 yr (average) |

|

Average no. of physicians |

140,075 |

407,201 |

216,001 |

|

Causes |

Occupational negligence resulting in death or injury |

Medical practice (including occupational negligence resulting in death or injury) |

Manslaughter by negligence |

|

Total (average/yr) |

354 (32.2) |

202 (11.2) |

7 (1.4) |

|

Conv. (average/yr) |

239 (21.7) |

32 (1.8) |

4 (0.8) |

|

Acq. (average/yr) |

115 (10.5) |

6 (0.3) |

3 (0.6) |

Table 2.Comparison of criminal trial outcomes for occupational negligence resulting in death or injury between the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the KMA Research Institute for Healthcare Policy

|

Category |

MOHW |

RIHP |

Difference |

|

Investigated period |

2019–2023 (5 yr) |

2014–2018 (5 yr) |

- |

|

Total cases |

192 |

173 |

19 |

|

Convictions |

135 |

117 |

+18 |

|

Acquittals |

57 |

56 |

+1 |

Table 3.Prosecutor’s office handling of cases involving physicians: occupational negligence resulting in death or injury: RIHP (2014–2018)

|

RIHP (2014–2018) |

Year |

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

Average |

|

Professionals |

895 |

1,024 |

1,016 |

1,051 |

1,248 |

1,047 |

|

Physicians |

677 (75.6) |

719 (70.2) |

704 (69.3) |

720 (68.5) |

877 (70.3) |

739 (70.6) |

Table 4.Prosecutor’s office handling of cases involving physicians: occupational negligence resulting in death or injury: MOHW (2019–2023)

|

MOHW (2019–2023) |

Year |

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

Average |

|

Professionals |

1,118 |

1,248 |

1,032 |

1,077 |

1,199 |

1,135 |

|

Physicians |

783 (70.0) |

868 (69.6) |

645 (62.5) |

668 (62.0) |

711 (59.3) |

735 (64.8) |

References

- 1. Shin H, Go DS, Yeo NG, Kim HN, Ok MS, Lee SI, Jeong HS, Yoon SJ, Yoon JH, Kim MJ, Kwon JH, Jang SY, Pyo JH, An JG, Kwon JS, Choi MY, Bae JE, Lee SB, Choi SY. A study on the promotion of public-centered medical reform [Internet]. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 23]. Available from: https://repository.kihasa.re.kr/handle/201002/47944

- 2. McDonald F. The criminalisation of medical mistakes in Canada: a review. Health Law J 2008;16:1-25.

- 3. Williams N. Gross negligence manslaughter in healthcare: the report of a rapid policy review [Internet]. GOV.UK; 2018 [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/williams-review-into-gross-negligence-manslaughter-in-healthcare

- 4. Kim HS, Lee JK, Kim KY. Current status and implications of the criminalization of medical practice [Internet]. Korean Medical Association, Research Institute for Healthcare Policy; 2022 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://rihp.re.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=research_report&wr_id=338

- 5. Faisant M, Papin-Lefebvre F, Rerolle C, Saint-Martin P, Rouge-Maillart C. Twenty-five years of French jurisprudence in criminal medical liability. Med Sci Law 2018;58:39-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0025802417737402

- 6. Vennedey CH. Ausgang strafrechtlicher Ermittlungsverfahren gegen Ärzte wegen Verdachts eines Behandlungsfehlers [Outcome of criminal investigations against physicians on suspicion of medical malpractice] [dissertation]. Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität Bonn; 2007 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:5M-11225

- 7. Prosecution Service. Annual crime analysis 06 crime statistics table–III: characteristics of offenders [Internet]. Prosecution Service; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.spo.go.kr/site/spo/crimeAnalysis.do

- 8. Lee JH. Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital newborn death case…medical staff finally ‘not guilty’. Doctors News [Internet]. 2022 Dec 15 [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.doctorsnews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=147567

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Beauty and Fatality: A Forensic Perspective on Periprocedural Deaths after Aesthetic Procedures, and Insights for Death Investigation and Public Health Safety

Sohyung Park, Sung Wook Choi, Duk Hoon Kim, Minjung Kim, Min Jee Park, Jung Sik Jang, Seon Jung Jang, Jeong Hwa Kwon, Yooha Don, Hyejeong Kim

Korean Journal of Legal Medicine.2025; 49(4): 133. CrossRef