Abstract

Globally, rapid population aging—particularly in Korea—has extended life expectancy but not proportionally extended healthy life expectancy, resulting in longer periods of illness or disability and a higher demand for complex medical and social care. Therefore, prolonging healthy life and improving health-related quality of life have become primary objectives in geriatric medicine and rehabilitation. Geriatric rehabilitation is a critical intervention aimed at optimizing the functioning of older adults and pre-morbidly frail individuals who have lost independence due to acute illness or injury. For many older patients, the goal shifts from complete recovery to achieving a new equilibrium, maximizing autonomy despite greater dependency. Geriatric rehabilitation also targets key geriatric syndromes such as frailty, recognizing it as a dynamic and potentially reversible state that provides a crucial “time window” for intervention. This review summarizes the core principles and structural elements essential for geriatric rehabilitation, emphasizing the implementation challenges within the Korean healthcare system. Unlike the European consensus, which supports structured inpatient and outpatient services with seamless transitions of care guided by Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, the Korean healthcare system remains fragmented and heavily centered on acute hospitals. This highlights the urgent need for a systematic model to integrate care facilities and strengthen interprofessional collaboration to support community-based “aging in place.” Effective geriatric rehabilitation requires multidisciplinary teams and multifaceted approaches to optimize quality of life, social participation, and independent living. Despite its importance, substantial awareness gaps and policy barriers persist, underscoring an urgent call to action.

-

Keywords: Aging; Frailty; Geriatric; Rehabilitation; Delivery of health care

Introduction

Globally, aging-related health challenges are reshaping the foundation of medical care. Korea entered a super-aged society in 2024, with individuals aged 65 years and older exceeding 20% of the population, drawing global attention as the country with the fastest aging rate in the world [

1]. Korea is not only aging most rapidly but is also projected to have the world’s highest life expectancy by 2030—91 years for women and 84 years for men [

2]. Although increased life expectancy is often celebrated as a major public health achievement, it does not necessarily correspond to a proportional extension of healthy life expectancy. Without such parallel progress, societies face the inevitability of longer life spans accompanied by illness or disability and a rapid expansion in populations requiring complex medical and social care [

3]. While healthy and independent aging remains a universal goal, the reality is that many individuals will experience prolonged periods of impaired health or functional dependency in later life.

Older adults often experience diminished independence due to functional decline associated with aging and multiple chronic diseases. Most geriatric diseases are chronic degenerative conditions closely linked to frailty and disabilities that limit independent daily activities, thereby reducing quality of life and creating a significant socioeconomic burden [

4,

5]. Thus, prolonging healthy life and improving health-related quality of life are central objectives of geriatric medicine and rehabilitation. Geriatric rehabilitation has evolved to help older adults with disabilities recover lost physical, psychological, or social functions so that they can regain greater independence, live in personally fulfilling environments, and sustain meaningful social engagement [

4,

6]. It involves comprehensive programs designed to optimize the functioning of older adults, particularly those who were pre-morbidly frail and have lost independence following acute illness or injury.

In this review, we summarize the core principles of geriatric rehabilitation and outline the structural components necessary for its integration into clinical practice. Particular attention is given to the challenges of implementing geriatric rehabilitation in both hospital-based outpatient and inpatient settings, drawing on the Korean healthcare system’s experience, where aging-related health concerns are rapidly intensifying. The discussion highlights the organizational, cultural, and policy factors that affect the accessibility and delivery of rehabilitation programs in real-world practice.

Ethics statement

This was a literature-based study; therefore, neither approval by the Institutional Review Board nor the obtainment of informed consent was required.

Definition and core concepts of geriatric rehabilitation

As population aging accelerates, geriatric diseases are becoming increasingly prevalent in clinical practice. Even without specialized geriatric care, the majority of outpatient and inpatient populations consist of older adults, and the number of the oldest old (i.e., those in their 80s and 90s) is rising particularly rapidly [

7]. Most individuals in this age group experience degenerative changes and are predisposed to frailty and fragility [

8,

9]. The demand for comprehensive rehabilitation addressing conditions such as frailty, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, fragility fractures, and disuse syndrome—each contributing to significant functional decline and increased dependence in activities of daily living—has grown markedly in recent decades. This growing need has sparked interest in applying rehabilitation principles specifically to older adults who are physically frail and dependent, a movement that began to take shape in the early 1990s [

10,

11]. Grounded in the framework of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO-ICF) and the WHO rehabilitation cycle, geriatric rehabilitation has been conceptualized as a multidimensional process encompassing diagnostic, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions [

12]. Its overarching goal is to optimize functional capacity, enhance activity levels, and maintain social participation in older adults living with impairments and disabilities [

6]. However, for many older patients, especially those with multiple comorbidities and multifactorial deficits, full restoration of function may not be a realistic objective. Instead, the focus shifts toward achieving attainable, patient-centered goals. Thus, the appropriate aim is often to reach a new balance that may entail greater dependency while preserving autonomy and self-management to the greatest extent possible [

13].

Geriatric rehabilitation programs emphasize patient-centered goals that reflect individual preferences established through co-creation with patients and their caregivers. These programs can be delivered in a variety of settings, depending on national policies, reimbursement structures, and local resources [

13]. Geriatric rehabilitation may be implemented as outpatient, hospital-based, nursing home-based, or community-based services [

6]. Patients suitable for rehabilitation are typically older adults whose intrinsic capacity and functional ability are compromised by multimorbidity and geriatric syndromes but who retain the potential to improve clinically and functionally through targeted interventions [

14,

15]. Such patients should be active participants in the rehabilitation process. Geriatric syndromes and diseases—most notably frailty (both physical and cognitive) and sarcopenia (including age-related and secondary forms)—represent quintessential conditions embodying the core principles of geriatric medicine [

16-

18]. Within the framework of geriatric rehabilitation, it is essential to recognize that geriatric syndromes do not correspond to discrete disease entities. Rather, they are interrelated conditions that profoundly affect functional ability, independence, and overall quality of life in older adults [

19].

Frailty is a clinical state characterized by increased vulnerability to dependency and/or mortality when exposed to stressors [

20]. It represents a biological syndrome of diminished physiological reserve and resistance to stress, arising from cumulative declines across multiple systems and resulting in susceptibility to adverse outcomes [

21,

22]. Frailty is a well-established predictor of disability and mortality and is also associated with poorer outcomes following rehabilitation interventions in geriatric settings [

23]. Although various definitions of frailty exist, 2 major conceptual frameworks are widely recognized: the phenotype-based model [

24] and the deficit accumulation model (frailty index) [

25]. The frailty index is based on the accumulation of health deficits across physical, psychological, cognitive, and social domains. The phenotype-based model (Fried model) is the most widely used in clinical practice and comprises 5 interrelated features—slow gait speed, low grip strength, poor endurance, low physical activity, and unintentional weight loss. The presence of 3 or more criteria indicates frailty, while 1 or 2 denote pre-frailty. Frailty is not a standalone disease, nor is it a static or irreversible condition. It is a dynamic and potentially reversible state—especially if addressed during the “frailty time-window,” a critical transitional period in the aging process during which individuals shift from relative independence (“full performance”) toward frailty and are at risk of progressing to disability [

26]. This concept holds particular importance in geriatric rehabilitation, as it represents a pivotal window of opportunity for timely and effective intervention [

23].

Structures and settings of geriatric rehabilitation

The WHO Rehabilitation 2030 initiative was launched to make rehabilitation accessible to everyone who needs it [

27,

28]. This initiative is closely aligned with the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing and underscores rehabilitation as an essential component of integrated care, emphasizing its clinical value and social importance. Both initiatives affirm that aging well is not merely about living longer—it is about living better. Rehabilitation serves as the driving force behind healthy aging by enabling older adults to recover, adapt, and thrive despite chronic conditions or functional decline. The WHO Rehabilitation 2030 framework is not only compatible with geriatric rehabilitation but also provides a powerful global structure that can elevate and integrate it into healthcare systems worldwide [

27,

28]. However, the organization and delivery of rehabilitation vary widely across countries, leading to inconsistent outcomes and unequal access [

13-

15,

29]. Grund et al. [

6] reported substantial international differences in how geriatric rehabilitation is structured and delivered. They emphasized the need to achieve consensus on what geriatric rehabilitation should entail and to develop internationally harmonized approaches that could be applied consistently across rehabilitation settings.

According to the European consensus statement, the structure of geriatric rehabilitation encompasses both inpatient and outpatient settings. Inpatient rehabilitation can take place in nursing homes, geriatric rehabilitation centers, specialized geriatric hospitals, or acute care hospital units [

14]. Admission to each setting should be determined by clearly defined clinical criteria that are objectively assessed and measured. Seamless care transitions should allow patients to move between different rehabilitation environments based on clinical progress and individual needs. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), incorporating the perspectives of patients and informal caregivers, should be applied within a co-creation framework to design tailored rehabilitation plans [

22]. This structured model underscores the importance of defining roles across levels of care to ensure continuity, specialization, and efficiency in service delivery [

30].

By contrast, the Korean healthcare system—although highly developed for advanced, disease-centered care—lacks an appropriate framework for comprehensive and integrated services such as geriatric care [

1,

31]. Geriatric rehabilitation in Korea remains largely concentrated in acute hospitals, with few dedicated rehabilitation centers or structured outpatient programs [

27]. Consequently, older adults frequently experience fragmented transitions between hospitals, community-based facilities, and long-term care institutions, resulting in discontinuity of care. Establishing a systematic model that clearly delineates the functions of each facility and integrates them into the overall healthcare system is therefore a critical priority [

27]. Such a model must be adapted to the specific supply–demand conditions of the Korean context, where rapid population aging has intensified the need for rehabilitation. Furthermore, successful implementation requires reorganizing healthcare delivery to enhance interprofessional collaboration and to promote seamless coordination across acute, post-acute, and community-based care settings [

32].

Recently, Korea’s national healthcare strategy for addressing the challenges of a super-aged society has increasingly emphasized community-based care [

33,

34]. This approach seeks to enable older adults to receive necessary health services while remaining in their homes and active within their communities—a concept widely recognized as “aging in place” [

33]. This paradigm shift reflects growing recognition that institutional care alone cannot adequately meet the multifaceted and long-term needs of the aging population. According to a survey by the European Geriatric Medicine Society Special Interest Group on geriatric rehabilitation, the primary conditions leading to admission to geriatric rehabilitation units were neurological disorders—predominantly stroke—and fractures, particularly hip fractures [

14]. These findings underscore the necessity of developing geriatric rehabilitation systems that address both acute disabling events and the long-term functional challenges they pose.

Specific considerations for rehabilitation programs

In geriatric care settings, rehabilitation should aim to minimize functional impairment and activity limitations while maximizing social participation, even when restoration of pre-morbid body structure and function is not feasible. This often requires the use of assistive technologies as well as cultural and environmental adaptations. Rehabilitation programs should integrate psychosocial components of health and well-being and employ evidence-based behavioral change approaches to enhance adherence and long-term outcomes [

6,

13,

15,

35].

Treatment intensity should be individualized according to each patient’s needs. For older adults, adjustments are frequently required to accommodate reduced physical function and exercise capacity. An exploratory study that examined the content and outcomes of physical fitness training in orthopedic geriatric rehabilitation found that most training programs were generally low in intensity compared with established guidelines [

36]. Given these limitations, it is important to emphasize that effective geriatric rehabilitation typically requires longer training durations to achieve meaningful improvements.

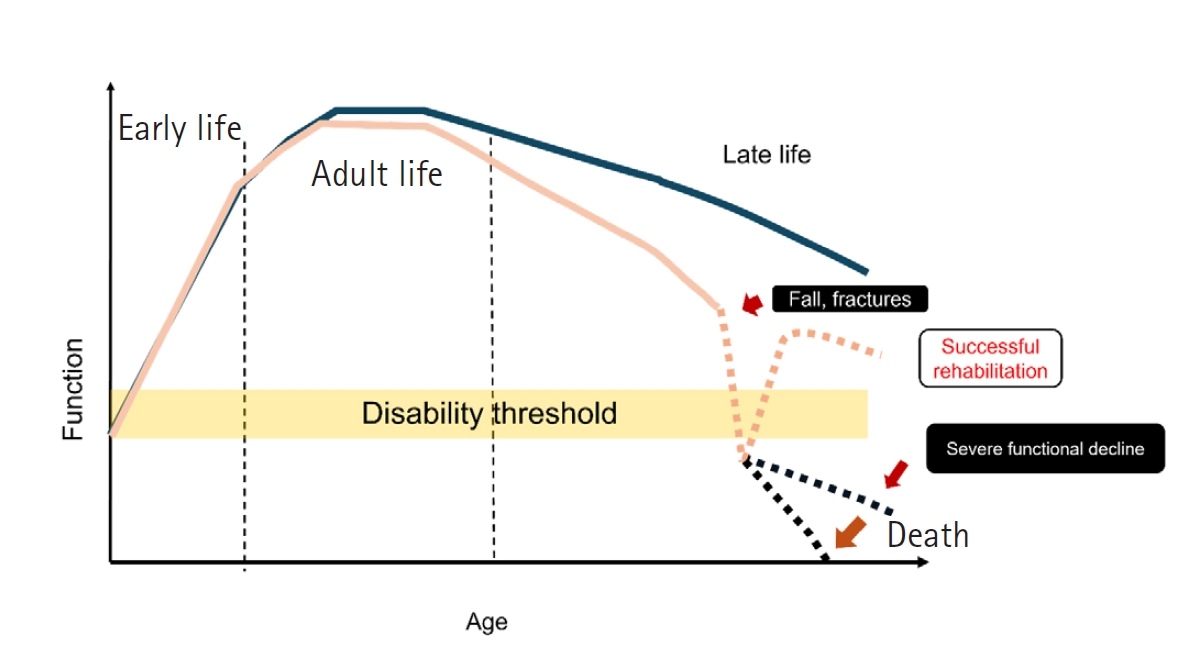

Within the broad domain of geriatric rehabilitation, patients present with a wide array of specific conditions, including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, hip fracture, amputation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure, cognitive impairment, and COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019). Because each case involves distinct factors and varying degrees of multimorbidity, condition-specific protocols alone are insufficient. Environmental and contextual factors—such as family support, resilience, and patient motivation—must be carefully considered, as they strongly influence rehabilitation outcomes. Evidence from systematic reviews and clinical experience in both geriatric rehabilitation clinics and inpatient units supports the use of individualized, evidence-informed rehabilitation strategies tailored to older adults [

13,

23,

37]. Inpatient geriatric rehabilitation encompasses a continuum of care designed to meet the needs of older adults experiencing functional decline. Patients may require rehabilitation following acute illness in an acute geriatric unit or due to chronic disease–related deterioration in a subacute unit. The indications for inpatient rehabilitation can extend to chronic functional decline, especially among those meeting criteria for frailty or sarcopenia. Older adults with progressive loss of independence in activities of daily living (ADLs), often resulting from declining mobility and cognitive function over 6 months to 1 year, are suitable candidates for short-term, comprehensive, and integrated rehabilitation programs. Additional indicators include recurrent falls, poor mobility following falls, and fragility fractures, all of which contribute to a downward trajectory in functional status. This progression reflects the lifelong vulnerability of frail individuals to fall-related injuries and subsequent disability. Without timely and appropriate intervention, these patients face a markedly increased risk of severe functional decline or death. However, accumulating evidence shows that when rehabilitation services are delivered promptly and effectively, many older adults can regain their pre-morbid functional levels, highlighting the crucial importance of early rehabilitation in preventing long-term disability [

19,

30,

38,

39] (

Fig. 1).

A multifaceted rehabilitation approach is essential to effectively support frail older adults within geriatric rehabilitation programs [

40]. The RESORT (Rituximab Extended Schedule or Retreatment Trial) study demonstrated that frailer geriatric inpatients tend to have more complex comorbidities and impaired nutritional, physical, and psychological parameters. Cognitive impairment, delirium, comorbid conditions, and anxiety at admission were predictive of worsening frailty during rehabilitation. The study recommended that these factors be assessed and addressed early through interdisciplinary care [

23]. The key components of multifaceted rehabilitation include physical rehabilitation, nutritional support, cognitive and psychological care, social and environmental adjustment, and medical optimization.

Geriatric rehabilitation team

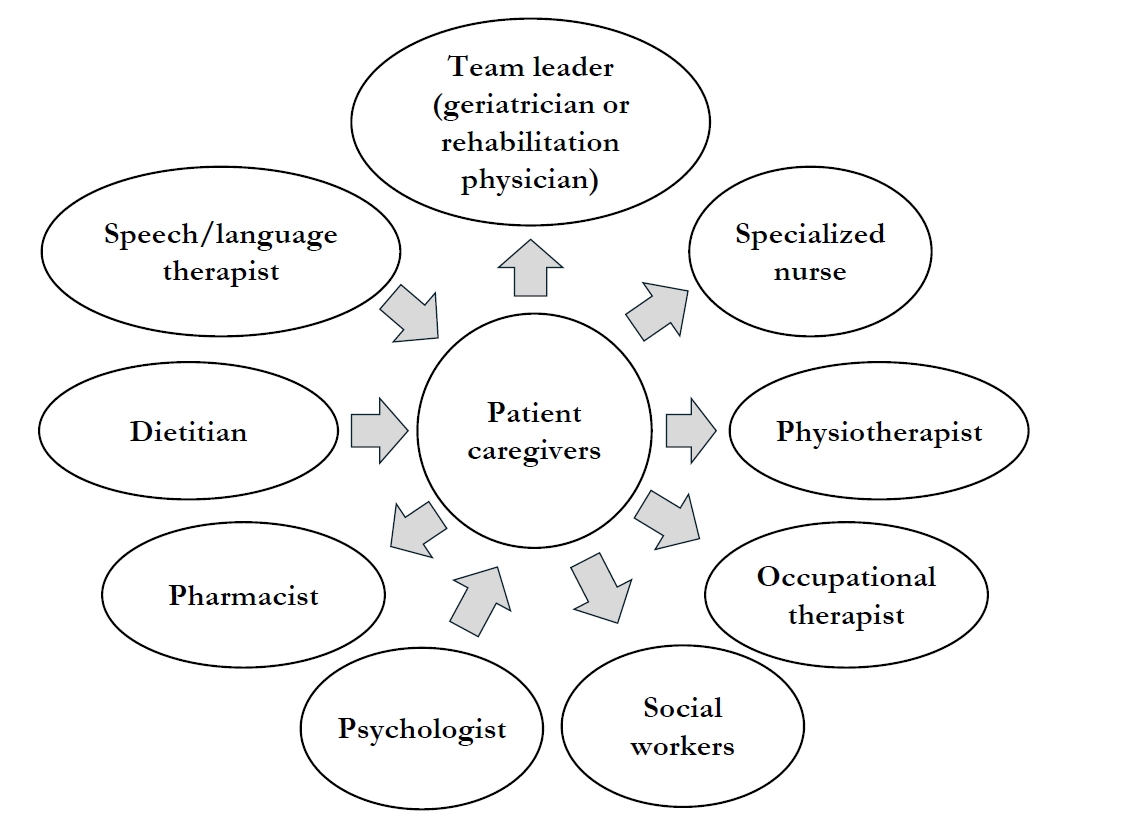

A geriatric rehabilitation team is fundamentally multidisciplinary, designed to address the complex, interrelated medical, psychological, and social needs of older adults. Since most geriatric patients present with multimorbidity, frailty, or disability, their care requires the coordinated expertise of multiple professionals rather than a single discipline. Geriatric rehabilitation team consists of the team leader, core team members, extended team members and collaborators [

6,

13,

35] (

Fig. 2).

In Europe, most geriatric rehabilitation teams are led by geriatricians (95%, according to consensus surveys), reflecting the specialty’s comprehensive focus on multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and geriatric syndromes [

14]. In Korea and several other Asian countries, however, teams are often led by rehabilitation specialists, whose expertise lies in functional restoration, physical medicine, and disability management [

41]. The team leader is responsible for coordinating assessments, setting rehabilitation goals, and ensuring alignment between medical management and rehabilitation priorities [

15]. Core team members generally include specialized nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social workers. Extended team members typically comprise psychologists or neuropsychologists, dietitians, pharmacists, and speech and language therapists. The specialized nurse plays a pivotal role by providing ongoing patient monitoring, wound and medication management, and acting as a central communication link among patients, families, and the interdisciplinary team. The physical therapist focuses on mobility enhancement, balance training, gait correction, fall prevention, and individualized exercise regimens to restore functional movement. Occupational therapists facilitate independence in ADLs—such as dressing, feeding, toileting, and home adaptation—while supporting strategies to enhance safety and autonomy. The social worker evaluates social support networks, caregiver burden, and financial constraints, and coordinates access to community-based resources that promote long-term care and “aging in place.”

Among the extended team members, the psychologist or neuropsychologist conducts cognitive and behavioral assessments, manages emotional well-being, and provides coping support for both patients and caregivers. The dietitian or nutritionist develops individualized nutrition plans targeting conditions such as sarcopenia, frailty, and post-fracture recovery, emphasizing adequate protein intake and supplementation. The pharmacist ensures safe and effective medication use, minimizes risks associated with polypharmacy, and provides education on medication adherence. The speech and language therapist assesses and rehabilitates swallowing disorders (dysphagia) and communication impairments, particularly following stroke or in neurodegenerative conditions.

The team operates under the framework of the CGA, which integrates multidisciplinary inputs into a unified and adaptive rehabilitation plan [

42,

43]. Families and caregivers are regarded as essential partners in this process, actively participating in goal setting, education, and ongoing follow-up. Regular multidisciplinary meetings facilitate the continuous review and adjustment of rehabilitation goals, early detection of complications, and effective communication among team members. Ultimately, the mission of the geriatric rehabilitation team extends beyond physical recovery to encompass the enhancement of quality of life, social participation, and independent living for older adults. Its effectiveness depends on the ability to balance medical stabilization, functional restoration, and psychosocial reintegration while respecting each patient’s individual values and preferences.

Conclusion

Key strategies for effective geriatric rehabilitation include accurate diagnosis of underlying problems and the comprehensive use of assessment tools—particularly the active application of CGA. Continuous, longitudinal monitoring of aging-related changes and physical and cognitive function in older adults enables the development of tailored prevention, recovery, and adaptation strategies. Appropriate and timely medical and rehabilitative interventions should be implemented across various clinical settings, including acute hospitals, post-acute care facilities, long-term care institutions, and home or community environments. These strategies encompass multimodal exercise programs, nutritional optimization, management of geriatric syndromes, and individualized case management approaches. Despite the growing need, awareness of geriatric rehabilitation remains limited, and substantial policy barriers persist. Therefore, a concerted call to action is necessary to highlight the essential role of comprehensive and integrated rehabilitation in addressing geriatric health challenges and promoting healthy aging.

-

Authors’ contribution

All work was done by Jae-Young Lim.

-

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korean ARPA-H Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00507183).

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Critical role of early rehabilitation in mitigating long-term disability.

Fig. 2.Multidisciplinary teams in geriatric rehabilitation.

References

- 1. Ji S, Jung HW, Baek JY, Jang IY, Lee E. Geriatric medicine in South Korea: a stagnant reality amidst an aging population. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2023;27:280-285. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.23.0199

- 2. Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li G, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet 2017;389:1323-1335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32381-9

- 3. Lim JY. What should geriatric medicine do in the new normal of life expectancy? Ann Geriatr Med Res 2018;22:1-2. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.2018.22.1.1

- 4. Wells JL, Seabrook JA, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Knoefel F. State of the art in geriatric rehabilitation. Part II: clinical challenges. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:898-903. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04930-4

- 5. Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S, Barakovic Husic J, Tomsone S, Krejcar O, Kuca K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7762-5

- 6. Grund S, Gordon AL, van Balen R, Bachmann S, Cherubini A, Landi F, Stuck AE, Becker C, Achterberg WP, Bauer JM, Schols JM. European consensus on core principles and future priorities for geriatric rehabilitation: consensus statement. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:233-238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00274-1

- 7. Do HK, Lim JY. Rehabilitation strategy to improve physical function of oldest-old adults. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2015;19:61-70. https://doi.org/10.4235/jkgs.2015.19.2.61

- 8. Lim JY. Fragility fracture care: an urgent need to implement the integrated model of geriatric care. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2019;23:1-2. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.19.0011

- 9. Dovjak P, Iglseder B, Rainer A, Dovjak G, Weber M, Pietschmann P. Prediction of fragility fractures and mortality in a cohort of geriatric patients. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024;15:2803-2814. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13631

- 10. Granerus AK. Rehabilitation in a geriatric perspective: new approach, new way of working. Lakartidningen 1993;90:4325-4329.

- 11. Gershkoff AM, Cifu DX, Means KM. Geriatric rehabilitation. 1. Social, attitudinal, and economic factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993;74:S402-S405.

- 12. Gladman JR. The international classification of functioning, disability and health and its value to rehabilitation and geriatric medicine. J Chin Med Assoc 2008;71:275-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70122-9

- 13. Achterberg WP, Cameron ID, Bauer JM, Schols JM. Geriatric rehabilitation-state of the art and future priorities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:396-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.02.014

- 14. Grund S, van Wijngaarden JP, Gordon AL, Schols JM, Bauer JM. EuGMS survey on structures of geriatric rehabilitation across Europe. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:217-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00273-2

- 15. van Balen R, Gordon AL, Schols JM, Drewes YM, Achterberg WP. What is geriatric rehabilitation and how should it be organized?: a Delphi study aimed at reaching European consensus. Eur Geriatr Med 2019;10:977-987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-019-00244-7

- 16. Currie DM, Gershkoff AM, Cifu DX. Geriatric rehabilitation. 3. Mid- and late-life effects of early-life disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993;74:S413-S416.

- 17. Setiati S, Harimurti K, Fitriana I, Dwimartutie N, Istanti R, Azwar MK, Aryana IG, Sunarti S, Sudarso A, Ariestine DA, Dwipa L, Widajanti N, Riviati N, Mulyana R, Rensa R, Mupangati YM, Budiningsih F, Sari NK. Co-occurrence of frailty, possible sarcopenia, and malnutrition in community-dwelling older outpatients: a multicentre observational study. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:91-101. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0144

- 18. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:780-791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

- 19. Jonsson A, Gustafson Y, Schroll M, Hansen FR, Saarela M, Nygaard H, Laake K, Jonsson PV, Valvanne J, Dehlin O. Geriatric rehabilitation as an integral part of geriatric medicine in the Nordic countries. Dan Med Bull 2003;50:439-445.

- 20. Hoogendijk EO, Dent E. Trajectories, transitions, and trends in frailty among older adults: a review. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2022;26:289-295. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.22.0148

- 21. Kang MG, Kim OS, Hoogendijk EO, Jung HW. Trends in frailty prevalence among older adults in Korea: a nationwide study from 2008 to 2020. J Korean Med Sci 2023;38:e157. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e157

- 22. Jung HW. Frailty as a clinically relevant measure of human aging. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2021;25:139-140. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.21.0106

- 23. Tolley AP, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Characteristics of geriatric rehabilitation inpatients based on their frailty severity and change in frailty severity during admission: RESORT. Mech Ageing Dev 2022;207:111712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2022.111712

- 24. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:255-263. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255

- 25. Rockwood K. Conceptual models of frailty: accumulation of deficits. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:1046-1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.03.020

- 26. Singh M, Alexander K, Roger VL, Rihal CS, Whitson HE, Lerman A, Jahangir A, Nair KS. Frailty and its potential relevance to cardiovascular care. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:1146-1153. https://doi.org/10.4065/83.10.1146

- 27. Frontera WR, DeGroote W, Ghaffar A. Importance of health policy and systems research for strengthening rehabilitation in health systems: a call to action to accelerate progress. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2023;27:277-279. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.23.0173

- 28. Gimigliano F, Negrini S. The World Health Organization “Rehabilitation 2030: a call for action”. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017;53:155-168. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04746-3

- 29. van Tol LS, Lin T, Caljouw MA, Cesari M, Dockery F, Everink IH, Francis BN, Gordon AL, Grund S, Matchekhina L, Bazan LM, Topinkova E, Vassallo MA, Achterberg WP, Haaksma ML. Post-COVID-19 recovery and geriatric rehabilitation care: a European inter-country comparative study. Eur Geriatr Med 2024;15:1489-1501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-024-01030-w

- 30. Gough C, Damarell RA, Dizon J, Ross PD, Tieman J. Rehabilitation, reablement, and restorative care approaches in the aged care sector: a scoping review of systematic reviews. BMC Geriatr 2025;25:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-025-05680-8

- 31. Jung HW, Lim JY. Geriatric medicine, an underrecognized solution of precision medicine for older adults in Korea. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2018;22:157-158. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.18.0048

- 32. Kim SH, Joo HJ, Kim JY, Kim HJ, Park EC. Healthcare policy agenda for a sustainable healthcare system in Korea: building consensus using the Delphi method. J Korean Med Sci 2022;37:e284. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e284

- 33. Cho MS, Kwon MY. Factors associated with aging in place among community-dwelling older adults in Korea: findings from a national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032740

- 34. Lee JY, Kim KJ, Kim JE, Yun YM, Sun ES, Kim CO. Differences in the health status of older adults in community and hospital cohorts. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:169-176. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0199

- 35. Bean JF, Orkaby AR, Driver JA. Geriatric rehabilitation should not be an oxymoron: a path forward. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:995-1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.12.038

- 36. Wattel EM, Groen WG, Visser D, van der Wouden JC, Meiland FJ, Hertogh CM, Gerrits KH. The content of physical fitness training and the changes in physical fitness and functioning in orthopedic geriatric rehabilitation: an explorative observational study. Disabil Rehabil 2025;May 19 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2025.2506823

- 37. Bachmann S, Finger C, Huss A, Egger M, Stuck AE, Clough-Gorr KM. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010;340:c1718. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c1718

- 38. Lim SK, Beom J, Lee SY, Lim JY. Functional outcomes of fragility fracture integrated rehabilitation management in sarcopenic patients after hip fracture surgery and predictors of independent ambulation. J Nutr Health Aging 2019;23:1034-1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-019-1289-4

- 39. Lim SK, Beom J, Lee SY, Kim BR, Ha YC, Lim JY. Efficacy of fragility fracture integrated rehabilitation management in older adults with hip fractures: a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2025;26:105321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2024.105321

- 40. Leach SJ, Larkin M, Gras LZ, Quiben MU, Miller KL, Lusardi MM, Hartley GW. A movement framework for older adults: application of the Geriatric 5Ms. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2025;May 16 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000473

- 41. Yoo SD. Interdisciplinary health model in geriatric rehabilitation. Geriatr Rehabil [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 10];13:4-12. Available from: https://www.kagrm.or.kr/file/journal/13/13_4.pdf

- 42. Yew E, Kropsky BA, Neufeld RR, Libow LS. The clinical utility of a comprehensive periodic assessment form for the geriatric rehabilitation patient. Gerontologist 1989;29:263-267. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/29.2.263

- 43. Wells JL, Seabrook JA, Stolee P, Borrie MJ, Knoefel F. State of the art in geriatric rehabilitation. Part I: review of frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:890-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(02)04929-8