Abstract

This study aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of aging with disability among polio survivors who continue to live with long-term sequelae. Although poliomyelitis has been eradicated in most regions, survivors entering older age face a dual challenge, as age-related decline overlaps with pre-existing impairments, creating a need for integrated management strategies. This narrative review examined the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and late effects of polio, with particular attention to post-polio syndrome, secondary musculoskeletal disorders, and other systemic conditions. International and Korean studies were compared to highlight similarities and contextual differences. Polio survivors frequently experience accelerated functional decline due to post-polio syndrome, fatigue, pain, musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., arthritis, osteoporosis, fractures), and cardiopulmonary dysfunction. Approximately 64% report major falls, with 35% sustaining fractures, often at vulnerable sites such as the hip or distal femur. Psychological distress, sleep disturbances, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease are also prevalent, further compounding frailty. In Korea, where most survivors are now over 60 years of age, epidemiological patterns differ from those of Western cohorts; however, systematic investigations remain limited. Polio survivors exemplify the dual burden of aging and long-term disability, underscoring the need to move beyond fragmented, symptom-focused care toward integrated, life course–oriented approaches. Anticipating and managing late effects, strengthening preventive strategies, and ensuring equitable healthcare access are essential for maintaining function, independence, and quality of life. Lessons drawn from polio survivors offer valuable insights for understanding aging with disability more broadly.

-

Keywords: Aging; Disability; Late effects; Poliomyelitis; Postpolio syndrome

Introduction

The global eradication of poliomyelitis through widespread vaccination represents one of the most remarkable public health achievements of the 20th century. However, tens of millions of polio survivors worldwide continue to live with the long-term sequelae of the disease [

1]. As polio survivors enter older age, the typical functional decline associated with natural aging is superimposed on pre-existing dysfunction, creating various late effects that compound their vulnerabilities [

2].

The concept of “late effects” refers to new or worsening health problems that arise over time as a consequence of long-standing impairments [

3]. These effects exacerbate pre-existing disabilities and accelerate further functional decline in middle and older age [

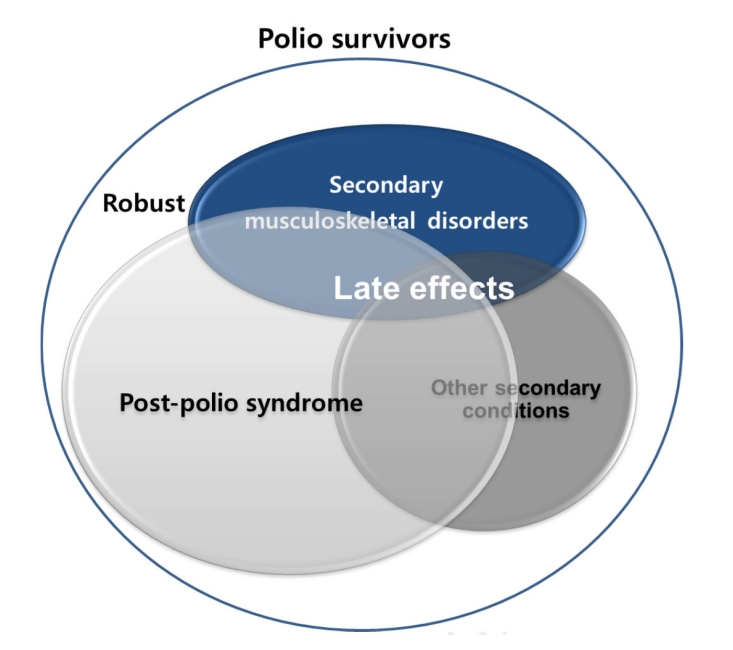

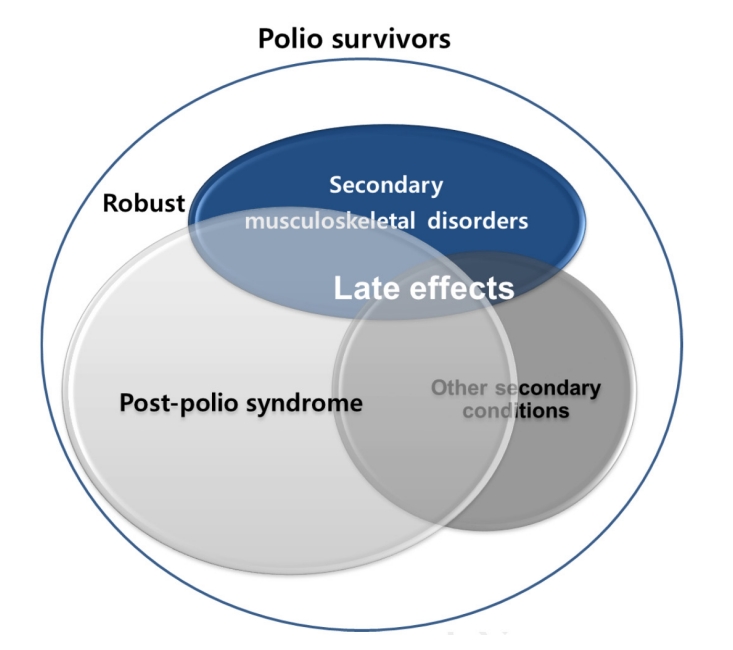

4]. Late effects of polio typically include post-polio syndrome (PPS), characterized by newly developed muscle weakness, fatigue, and pain decades after the acute infection, as well as secondary musculoskeletal complications such as joint stiffness, deformities, and premature degenerative changes, along with other secondary conditions (

Fig. 1). These conditions are often accompanied by age-related changes in muscle mass, strength, and cardiopulmonary function, thereby accelerating frailty—a strong predictor of adverse outcomes [

5]—and disability. Consequently, polio survivors experience premature aging, in which their biological age exceeds their chronological age. This aging process is accompanied by chronic comorbidities and declines in physical and functional capacity [

6], ultimately leading to a deterioration in quality of life at a relatively younger age.

The global aging population represents one of the most prominent demographic trends of the 21st century [

7], and worldwide attention to healthy and successful aging has been steadily increasing [

8]. However, the needs of people aging with long-term disabilities have been relatively overlooked in both clinical practice and policy [

4]. Polio survivors represent a paradigmatic group for examining these issues, given their clearly defined historical cohort, well-documented impairments, and increasing age. In Korea, the median age of polio survivors now exceeds 60 years, highlighting the urgency of addressing the health threats posed by late effects and their interaction with aging. Nonetheless, many healthcare providers continue to rely on fragmented approaches that focus primarily on patients’ chief complaints or symptoms, leaving individuals without adequate care tailored to their specific needs and conditions [

4]. As a result, the complex and multisystem challenges faced by this population remain insufficiently addressed.

From a life-course perspective, successful aging with disability should be understood as a multidimensional construct encompassing not only multidisciplinary medical care but also psychological resilience, social connectedness, and equitable access to healthcare services. For polio survivors, developing integrated strategies to prevent and mitigate late effects is essential for maintaining function and quality of life. This narrative review aims to synthesize current knowledge on aging with disability in polio survivors.

Ethics statement

This was a literature-based study; therefore, neither approval by an institutional review board nor the obtainment of informed consent was required.

Epidemiology of polio survivors and aging

Poliomyelitis is a disease caused by acute viral inflammation of motor neurons in the spinal cord that spread worldwide during the mid-20th century. While most infections were subclinical, a subset progressed to paralytic disease with lifelong sequelae. Mortality among paralytic cases ranged from 2% to 10%, with greater severity observed at older ages. With the introduction of effective vaccination programs, new cases dramatically declined worldwide. By the early 1980s, countries such as Korea had eliminated indigenous transmission, and in 2000, the World Health Organization declared the Western Pacific Region—including Korea—polio-free.

However, tens of millions of survivors remain worldwide [

1]. The United States has approximately 1.6 million polio survivors [

9], and European countries also report substantial numbers. In Scandinavia, where no new indigenous cases occur, immigration from polio-endemic regions has led to a dual demographic pattern of aging native-born survivors and younger immigrant survivors [

10]. In contrast, in Asia—including Japan, Taiwan, and Korea—survivors constitute one of the largest global cohorts, although systematic studies and coordinated healthcare responses remain limited.

Korea’s epidemiological trajectory lagged roughly a decade behind that of Western countries, with a peak incidence during the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly in the aftermath of the Korean War. Consequently, the survivor population remains relatively large, with the majority now in their 60s or older [

11]. Although official statistics on polio survivors in Korea are unavailable, an estimated 60,000 individuals are survivors based on data from the National Survey on Persons with Disabilities, which found that 5.2% of individuals with limb disabilities reported poliomyelitis as the cause [

12]. This estimate is more than twice the number of survivors in Japan [

13], likely reflecting delayed vaccine introduction and post-war sanitary conditions in Korea. Therefore, the demographic and clinical characteristics of Korean survivors may differ from those observed in developed countries where the disease has been more extensively studied [

14,

15].

International cohort studies consistently demonstrate that a large proportion of survivors experience new or worsening symptoms—such as fatigue, pain, and weakness—decades after the acute infection. Surveys in the United States suggest that up to 64% of survivors report new symptoms, and nearly half develop new weakness [

16]. Italian and Israeli studies also highlight the high prevalence of PPS and increased comorbidity risks, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic pain [

17,

18]. Similarly, data from Taiwan indicate significantly elevated risks of stroke, hypertension, and other chronic systemic diseases among survivors [

19,

20].

In Korea, the health challenges of polio survivors must be understood within the context of rapid socioeconomic development and substantial improvements in healthcare infrastructure over the past 6 decades. Such environmental and systemic transitions suggest that the clinical profiles and healthcare needs of Korean polio survivors may differ significantly from those reported in Western cohorts. To accurately capture these dynamics, a systematic nationwide study of Korean polio survivors is urgently needed. Such research would enable robust evaluation of long-term outcomes, inform tailored rehabilitation strategies, and guide policy development. More broadly, these efforts would contribute to understanding the broader phenomenon of aging with disability.

Late effects of polio

Depending on the stage of life, polio survivors experience a variety of problems following the onset of the initial disease. As individuals age, the natural functional decline associated with aging is superimposed on pre-existing disabilities, resulting in multiple late effects [

2,

11]. The key issues include persistent or newly emerging problems such as pain, fatigue, muscle weakness, functional impairment, and disability, including PPS. Because of these challenges, polio survivors often face limitations in independent activity and daily living. They frequently report depression, psychological and emotional distress, anxiety, and pain. Quality of life is reduced due to changes in social relationships, difficulty maintaining employment, and economic hardship [

21,

22]. As survivors grow older, ordinary age-related decline is compounded by pre-existing dysfunction, leading to an accumulation of late effects. New medical problems unrelated to polio also emerge in approximately 35% of survivors [

23]. These conditions may cause newly developed weakness due to denervation or impaired coordination of reinnervated muscles. Progressive deterioration of neuromuscular function results in muscle atrophy, reduced physical fitness, and cardiopulmonary dysfunction. In addition, polio survivors commonly experience psychological distress along with physical dysfunction and functional decline.

PPS, characterized by new weakness and fatigue decades after the initial infection, is widely regarded as the representative late effect of poliomyelitis. However, the range of late effects extends far beyond PPS, encompassing diverse neuromusculoskeletal complications such as osteoporosis, progressive muscle weakness, degenerative arthritis, trauma- and overuse-related syndromes (e.g., tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome), as well as fall-related injuries, balance disturbances, skeletal deformities, respiratory difficulties, cold intolerance, and systemic conditions including cardiovascular and metabolic disorders (

Fig. 1) [

24-

26].

PPS encompasses a wide range of physical and psychological symptoms, including newly developed weakness and fatigue arising after a 25–30-year period of stability following acute poliomyelitis [

4]. There has been ongoing controversy regarding its diagnostic criteria due to the absence of definitive objective evidence. Previously, newly observed muscle atrophy was proposed as an essential diagnostic feature of PPS, but this criterion was criticized for resulting in delayed diagnosis, as it typically reflects an end-stage manifestation. Currently, the European Federation of Neurological Societies diagnostic criteria, published in 2000, are most commonly used. These criteria include: (1) a confirmed history of poliomyelitis; (2) partial or near-complete functional recovery after the acute episode; (3) at least 15 years of stable neurological function; (4) gradual or abrupt onset of progressive and persistent muscle weakness or abnormal muscle fatigability (manifesting as decreased endurance, with or without generalized fatigue, muscle atrophy, or musculoskeletal pain); and (5) exclusion of other potential causes of the symptoms [

27].

Common symptoms associated with PPS include muscle and joint pain on the affected or unaffected side (89%), fatigue (86%), and new-onset weakness (83%) on the affected (69%) or unaffected (50%) side. New muscle atrophy (28%) and difficulties in activities of daily living (78%)—such as impaired walking (64%), difficulty climbing stairs (61%), and problems with dressing (17%)—are also characteristic of PPS [

28].

The presence and severity of PPS symptoms appear to correlate with the severity of the original poliomyelitis, and it has been suggested that factors such as residual muscle weakness, viral persistence, arthritis, and spinal stenosis act synergistically in its development [

29].

Secondary musculoskeletal disorders are a major issue and can often be misdiagnosed as PPS. Degenerative arthritis frequently develops due to the long-term use of joints under biomechanically suboptimal conditions. Although arthritis commonly occurs on the paralyzed side, it may also arise from overuse of the unaffected side. Sensory disturbances, wrist or hand arthritis, reduced agility, and weakness in the hands frequently result from chronic overuse. Other manifestations of overuse syndrome include upper-limb pain due to prolonged use of walking aids, joint pain in both upper and lower extremities, and spinal pain associated with asymmetry and abnormal gait patterns [

30,

31] (

Table 1).

Inactivity and disuse stemming from muscle weakness and paralysis are major contributors to osteoporosis in polio survivors. Osteoporosis and fall-related fractures are frequently observed during middle age. Muscle strength directly affects bone mineral density through interconnected biomechanical and metabolic mechanisms [

24], highlighting its crucial role in bone health. Most polio survivors are at high risk for fall-related injuries, as falls accelerate physical frailty and further deplete functional reserves [

32]. Indeed, 64% of survivors report at least 1 major fall, and 35% sustain fractures as a result [

33]. In a study of 317 Korean polio survivors, 68.5% reported at least 1 fall in the past year, and among those who fell, 42.5% experienced 2 or more falls within a single month [

34].

These rates are more than twice as high as those observed for falls and fall-related fractures in the general population of older adults. Among survivors, 80% of fractures were caused by falls, typically occurring in limbs affected by atrophy. Of particular concern, most fractures involved sites such as the hip and distal femur, where mobility and physical function may deteriorate even after adequate healing [

35]. Moreover, fear of falling itself is a major factor limiting physical activity. Comprehensive assessment and multidisciplinary management of fall-related problems are therefore essential for polio survivors.

In addition to secondary musculoskeletal disorders, other conditions not encompassed by PPS are frequently observed [

36] (

Table 1). For instance, a rare neuromuscular disorder such as myotonic dystrophy has been reported to mimic PPS in a polio survivor [

37], underscoring the need for careful differential diagnosis. The risks of pneumonia and respiratory distress increase due to respiratory muscle weakness, and sleep disorders, including central and obstructive complex sleep apnea, are common and contribute to poor sleep quality [

38]. In cases of bulbar-type poliomyelitis, dysphagia and speech disorders may coexist [

38,

39]. Cold intolerance—strongly linked to neurogenic vascular insufficiency, venous stasis, and excessive heat loss—occurs in approximately 29% of survivors when their extremities are exposed to cold environments [

39,

40]. The prevalence of other chronic conditions, such as metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, is also higher in polio survivors than in the general population. Reduced cardiovascular fitness, obesity, and hypercholesterolemia significantly increase cardiovascular risk [

26,

38]. Furthermore, pulmonary function in survivors shows a negative correlation with obesity, suggesting that body fat adversely affects lung capacity and may contribute to restrictive lung disease after controlling for muscle strength and activity level [

41]. Older adults with a history of poliomyelitis share many of the multidimensional health challenges commonly seen in the general population of older adults, arising from physiological, psychosocial, and environmental factors [

42].

Polio survivors also experience chronic emotional stress, anger (49%), and fear of falling (58%), along with a higher prevalence of peptic ulcers (80%) compared with the general population [

3,

43]. According to 3 North American studies, over 23% of polio survivors display a type A personality—characterized by competitiveness, time urgency, and a high-achieving temperament. Fatigue and muscle pain, accompanied by anxiety, frequent headaches, neck pain, and lower back pain, are more common among type A survivors than in non–type A individuals [

44,

45]. Moreover, polio survivors exhibit significantly lower health-related quality of life, particularly in the domains of mobility, activities of daily living, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [

46].

Why do late effects occur in polio survivors? Several hypotheses have been proposed. First, they may arise from the failure of reinnervation. Theoretically, maintaining axonal function becomes increasingly difficult after more than a decade, as neuronal metabolism becomes depleted due to abnormal axonal loss in surviving motor neurons. Consequently, gradual muscle weakness (approximately a 1% decrease per year on average), loss of muscle fibers, and progressive muscle atrophy develop. Second, late effects may result from chronic overuse of muscles previously affected by polio. With sustained overuse, these muscles remain in a state of continuous contraction, exacerbating weakness and functional loss [

19,

26,

30,

31]. A third hypothesis involves stress and hormonal alterations. Studies have reported that among polio survivors who developed new functional problems, significant decreases in growth hormone levels were observed in 9 out of 10 cases [

29]. Furthermore, a diminished reactive response to external stimuli has been associated with dysfunction of the reticular activating system [

30]. The impaired ability to maintain attention and process complex information rapidly appears to contribute to severe fatigue and exhaustion. In addition, the aging process itself may exacerbate functional decline in polio survivors through physiological changes across multiple organ systems—such as reduced respiratory capacity, elevated blood pressure, increased cholesterol and glucose levels, and joint stiffness. The number of spinal cord motor neurons remains relatively stable until approximately 60 years of age, after which it declines by about 1% annually, resulting in roughly a 30% loss by age 90. Similarly, both the number of muscle fibers and muscle strength are reduced by nearly half compared with young adults. Therefore, the combined effects of neuronal and muscular loss, together with declining cellular function associated with aging, likely contribute substantially to the development of late effects [

24,

31].

Conclusion

Polio survivors exemplify the unique challenges of aging with disability. Although the global eradication of poliomyelitis has eliminated new infections, the generation of survivors now entering older age faces a dual burden: the natural decline associated with aging compounded by the late effects of long-standing disability. These late effects accelerate functional deterioration and heighten vulnerability, underscoring the need for a paradigm shift from fragmented, symptom-focused care toward integrated, life course–oriented strategies for prevention and management [

3,

4]. Such an approach could more effectively address the needs of older adults with disabilities, reduce hospital utilization, and mitigate morbidity and mortality risks [

47].

The medical paradigm for polio survivors has evolved considerably over time. In the mid-20th century, the primary focus was on eradicating poliovirus and managing acute paralysis. During the 1960s and 1970s, orthopedic surgery became the central issue in survivor care [

26]. As these individuals transitioned into adulthood, the need for orthopedic interventions declined, and medical interest in polio correspondingly waned. Since the 1980s, however, as survivors have reached middle and older age, late effects have reemerged as major health concerns, reframing poliomyelitis not as a historical epidemic but as a lifelong condition [

48].

The experiences of polio survivors provide broader insights into the phenomenon of aging with disability. Individuals aging with long-term disabilities consistently report that healthy aging involves more than medical treatment—it requires self-management, social participation, psychological resilience, and independence in daily life [

5]. These perspectives reinforce the importance of anticipating late effects, designing preventive interventions, and ensuring equitable access to comprehensive, multidisciplinary care for those aging with long-standing disabilities. In caring for polio survivors, healthcare providers should adopt a life course approach grounded in a detailed assessment of functional abilities, activity patterns, residual sequelae, and the degree of functional limitation [

3].

By focusing on polio survivors as a paradigmatic group, we gain valuable insight into the historical evolution of disability medicine, the ongoing transition toward life course–based approaches, and the strategies needed to promote health, functional capacity, and dignity across the lifespan.

-

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: GYS. Data curation: GYS. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: JHH. Project administration: GYS. Funding acquisition: GYS. Writing–original draft: GYS, JHH. Writing–review & editing: GYS, JHH.

-

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center (PACEN) funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: RS-2025-02221859).

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.

Table 1.Secondary musculoskeletal disorders and other secondary conditions as late effects

|

Late effects |

Disorders |

|

Secondary musculoskeletal disorders |

Sensory disturbances (carpal tunnel syndrome or others) |

|

Joint pain in the upper and lower extremities |

|

Arthritis of the wrist or hand, knee |

|

Rotation cuff tear related to excessive use of the unaffected side |

|

Osteoporotic fractures |

|

Spinal pain related to asymmetry and abnormal gait patterns |

|

Decreased hand dexterity |

|

Other secondary conditions |

Pneumonia and respiratory diseases |

|

Sleep apnea |

|

Dysphagia and speech disorders |

|

Cold intolerance |

|

Metabolic syndrome |

|

Decreased fitness of the cardiovascular system |

|

Obesity |

|

Chronic emotional stress |

References

- 1. Bosch X. Post-polio syndrome recognised by European parliament. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00633-1

- 2. Cosgrove JL, Alexander MA, Kitts EL, Swan BE, Klein MJ, Bauer RE. Late effects of poliomyelitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987;68:4-7.

- 3. Maynard FM. Managing the late effects of polio from a life-course perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;753:354-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb27561.x

- 4. Lim JY. Aging with disability: what should we pay attention to? Ann Geriatr Med Res 2022;26:61-62. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.22.0068

- 5. Low MJ, Liau ZY, Cheong JL, Loh PS, Shariffuddin II, Khor HM. Impact of physical and cognitive frailty on long-term mortality in older patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:111-118. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0163

- 6. Yeo HS, Lim JY. Impact of physical activity level on whole-body and muscle-cell function in older adults. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:254-264. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0141

- 7. Choompunuch B, Lebkhao D, Suk-Erb W, Matsuo H. Health-promoting behaviors and their associations with frailty, depression, and social support in Thai community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional analysis. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:393-402. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.25.0080

- 8. Molton IR, Yorkston KM. Growing older with a physical disability: a special application of the successful aging paradigm. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2017;72:290-299. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw122

- 9. Halstead LS. Assessment and differential diagnosis for post-polio syndrome. Orthopedics 1991;14:1209-1217. https://doi.org/10.3928/0147-7447-19911101-09

- 10. Vreede KS, Sunnerhagen KS. Characteristics of patients at first visit to a polio clinic in Sweden. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150286. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150286

- 11. Bang H, Suh JH, Lee SY, Kim K, Yang EJ, Jung SH, Jang SN, Han SJ, Kim WH, Oh MG, Kim JH, Lee SG, Lim JY. Post-polio syndrome and risk factors in Korean polio survivors: a baseline survey by telephone interview. Ann Rehabil Med 2014;38:637-647. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2014.38.5.637

- 12. Ministry of Health and Welfare. National Survey on Persons with Disabilities. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2009.

- 13. Takemura J, Saeki S, Hachisuka K, Aritome K. Prevalence of post-polio syndrome based on a cross-sectional survey in Kitakyushu, Japan. J Rehabil Med 2004;36:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1080/16501970310017423

- 14. Dalakas MC, Elder G, Hallett M, Ravits J, Baker M, Papadopoulos N, Albrecht P, Sever J. A long-term follow-up study of patients with post-poliomyelitis neuromuscular symptoms. N Engl J Med 1986;314:959-963. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198604103141505

- 15. Agre JC, Grimby G, Rodriquez AA, Einarsson G, Swiggum ER, Franke TM. A comparison of symptoms between Swedish and American post-polio individuals and assessment of lower limb strength: a four-year cohort study. Scand J Rehabil Med 1995;27:183-192.

- 16. Windebank AJ, Litchy WJ, Daube JR, Kurland LT, Codd MB, Iverson R. Late effects of paralytic poliomyelitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology 1991;41:501-507. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.41.4.501

- 17. Ragonese P, Fierro B, Salemi G, Randisi G, Buffa D, D’Amelio M, Aloisio A, Savettieri G. Prevalence and risk factors of post-polio syndrome in a cohort of polio survivors. J Neurol Sci 2005;236:31-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2005.04.012

- 18. Shiri S, Wexler ID, Feintuch U, Meiner Z, Schwartz I. Post-polio syndrome: impact of hope on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:824-830. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.623755

- 19. Wu CH, Liou TH, Chen HH, Sun TY, Chen KH, Chang KH. Stroke risk in poliomyelitis survivors: a nationwide population-based study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:2184-2188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.020

- 20. Kang JH, Lin HC. Comorbidity profile of poliomyelitis survivors in a Chinese population: a population-based study. J Neurol 2011;258:1026-1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5875-y

- 21. Ahlstrom G, Karlsson U. Disability and quality of life in individuals with postpolio syndrome. Disabil Rehabil 2000;22:416-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/096382800406031

- 22. Halstead LS, Silver JK. Nonparalytic polio and postpolio syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000;79:13-18. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200001000-00005

- 23. Bartels MN, Omura A. Aging in polio. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2005;16:197-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2004.06.011

- 24. Riviati N, Darma S, Reagan M, Iman MB, Syafira F, Indra B. Relationship between muscle mass and muscle strength with bone density in older adults: a systematic review. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:1-14. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0113

- 25. Ivanyi B, Nollet F, Redekop WK, de Haan R, Wohlgemuht M, van Wijngaarden JK, de Visser M. Late onset polio sequelae: disabilities and handicaps in a population-based cohort of the 1956 poliomyelitis outbreak in The Netherlands. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:687-690. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90173-9

- 26. Nielsen NM, Rostgaard K, Askgaard D, Skinhoj P, Aaby P. Life-long morbidity among Danes with poliomyelitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:385-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00474-x

- 27. Farbu E, Rekand T, Gilhus NE. Post-polio syndrome and total health status in a prospective hospital study. Eur J Neurol 2003;10:407-413. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00613.x

- 28. Halstead LS. Post-polio syndrome. Sci Am 1998;278:42-47. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0498-42

- 29. Klingbeil H, Baer HR, Wilson PE. Aging with a disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:S68-S73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.014

- 30. Klein MG, Keenan MA, Esquenazi A, Costello R, Polansky M. Musculoskeletal pain in polio survivors and strength-matched controls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:1679-1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.01.041

- 31. Klein MG, Whyte J, Keenan MA, Esquenazi A, Polansky M. The relation between lower extremity strength and shoulder overuse symptoms: a model based on polio survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:789-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90113-8

- 32. Moncayo-Hernandez BA, Duenas-Suarez EP, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Relationship between social participation, children’s support, and social frailty with falls among older adults in Colombia. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2024;28:342-351. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0059

- 33. Silver JK, Aiello DD. Polio survivors: falls and subsequent injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002;81:567-570. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200208000-00002

- 34. Nam KY, Lee S, Yang EJ, Kim K, Jung SH, Jang SN, Han SJ, Kim WH, Lim JY. Falls in Korean polio survivors: incidence, consequences, and risk factors. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:301-309. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.2.301

- 35. Goerss JB, Atkinson EJ, Windebank AJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ. Fractures in an aging population of poliomyelitis survivors: a community-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69:333-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62217-4

- 36. Agre JC, Rodriquez AA, Franke TM. Strength, endurance, and work capacity after muscle strengthening exercise in postpolio subjects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:681-686. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90073-3

- 37. Lim JY, Kim KE, Choe G. Myotonic dystrophy mimicking postpolio syndrome in a polio survivor. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009;88:161-164. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e318190b935

- 38. Jubelt B. Post-polio syndrome. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2004;6:87-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-004-0018-3

- 39. Halbritter T. Management of a patient with post-polio syndrome. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2001;13:555-559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2001.tb00325.x

- 40. Jubelt B, Drucker J. Post-polio syndrome: an update. Semin Neurol 1993;13:283-290. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1041136

- 41. Han SJ, Lim JY, Suh JH. Obesity and pulmonary function in polio survivors. Ann Rehabil Med 2015;39:888-896. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2015.39.6.888

- 42. Lee JY, Kim KJ, Kim JE, Yun YM, Sun ES, Kim CO. Differences in the health status of older adults in community and hospital cohorts. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2025;29:169-176. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.24.0199

- 43. Kling C, Persson A, Gardulf A. The health-related quality of life of patients suffering from the late effects of polio (post-polio). J Adv Nurs 2000;32:164-173. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01412.x

- 44. Bruno RL, Frick NM. Stress and “type A” behavior as precipitants of post-polio sequelae: the Felician/Columbia Survey. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1987;23:145-155.

- 45. Bruno RL, Frick NM. The psychology of polio as prelude to post-polio sequelae: behavior modification and psychotherapy. Orthopedics 1991;14:1185-1193. https://doi.org/10.3928/0147-7447-19911101-06

- 46. Yang EJ, Lee SY, Kim K, Jung SH, Jang SN, Han SJ, Kim WH, Lim JY. Factors associated with reduced quality of life in polio survivors in Korea. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130448

- 47. Lim JY. Challenges and opportunities toward the decade of healthy ageing in the post-pandemic era. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2021;25:63-64. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.21.0064

- 48. Halstead LS, Rossi CD. Post-polio syndrome: clinical experience with 132 consecutive outpatients. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1987;23:13-26.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by