Abstract

Pediatric anesthesia presents unique challenges due to children’s distinct physiological and anatomical characteristics, including variations in drug metabolism, airway structure, and respiratory and circulatory regulation. Despite significant advances in patient safety that have reduced anesthesia-related mortality over recent decades, the declining pediatric population has made specialized training and clinical practice increasingly difficult. This narrative review addresses practical aspects of pediatric anesthesia, emphasizing patient monitoring, airway management, and recent clinical advances. Oxygen supply targets in children require careful titration to ensure adequate tissue oxygenation while avoiding oxygen toxicity and its associated complications, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retinopathy of prematurity. Quantitative monitoring of neuromuscular blockade, such as with train-of-four stimulation, is essential to prevent postoperative respiratory complications. Temperature monitoring is equally critical in pediatric surgery because children and neonates are highly susceptible to intraoperative hypothermia. Airway management in infants and young children is complicated by anatomical differences, and while video laryngoscopy offers advantages, evidence for its benefits in neonates remains inconclusive. Extubation strategies must be individualized, taking into account risks such as laryngospasm and airway obstruction, as both deep and awake extubation have demonstrated comparable safety profiles. Emerging modalities, such as transfontanelle ultrasonography, provide real-time cerebral blood flow assessment and enhance perioperative brain monitoring. Regional anesthesia techniques in neonates and infants reduce exposure to general anesthetics and facilitate faster recovery but require meticulous technique and monitoring to ensure safety. Multidisciplinary collaboration and effective communication with parents are essential to achieving optimal outcomes.

-

Keywords: Airway management; Child; Neuromuscular monitoring; Oxygen; Regional anesthesia

Introduction

Background

Children exhibit distinctive physiological and anatomical features—including differences in drug metabolism and responses, airway anatomy, and respiratory and circulatory regulatory mechanisms—that distinguish them markedly from adults. It is widely recognized that “pediatric patients are not simply small adults” [

1,

2]. Through continuous improvements in patient safety, anesthesia-related mortality has declined substantially, from 1:2,500 to 1:13,000 over the past 50 years [

3-

5]. However, the global total fertility rate (TFR) in 2021 was 2.3 children per woman, continuing its decline from 3.3 in 1990 and 2.8 in 2000 [

6]. In South Korea, the TFR dropped to 0.72 in 2023, the lowest among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries [

7].

As the number of pediatric patients decreases, specialized training in pediatric anesthesia has become increasingly complex. Even after achieving board certification, pediatric anesthesia continues to pose significant technical and clinical challenges for anesthesiologists.

Objectives

This narrative review aims to provide practical guidance drawn from recent literature to support clinicians in their daily practice, focusing on patient monitoring, airway management, and recent advances that can be directly implemented in pediatric anesthesia.

Ethics statement

Because this is a literature-based study, neither approval from an institutional review board nor informed consent was required.

Monitoring

Setting oxygen supply targets

Various equipment and techniques have been developed to optimize oxygen use, improving survival rates in pediatric patients with difficult airways [

8-

10]. However, the optimal target oxygen concentration during anesthesia in children remains uncertain. Several studies have explored complications related to oxygen concentration and use [

11-

13], underscoring the need to consider individualized oxygenation goals rather than simply maintaining a peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO

2) of 100%. An appropriate oxygen concentration enhances tissue oxygenation and tolerance to hypoxia while reducing the risk of surgical site infection [

14]. Conversely, excessive oxygen concentrations can cause absorption atelectasis due to airway closure and collapse, elevate pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary circulation, and decrease cerebral blood flow through systemic and cerebral vasoconstriction [

15-

17]. Moreover, oxygen toxicity resulting from reactive oxygen species may trigger inflammation and edema, leading to bronchopulmonary dysplasia and retinopathy of prematurity [

18-

21]. A recent review emphasized that no single universal range can define the optimal oxygen target during general anesthesia in pediatric patients. Anesthesiologists must determine oxygen concentration carefully, considering patient-specific factors before, during, and after surgery—such as lung function, oxygen consumption, and the presence of heart disease—to achieve optimal oxygenation [

14]. Additionally, pulse oximetry measures arterial oxygen saturation but not arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO

2). While pulse oximetry is effective for detecting hypoxia, it does not reduce mortality or accurately identify hyperoxia [

22]. The oxygen reserve index (ORi) quantifies oxygen reserves when SpO

2 is near 100%, providing an early warning of impending hypoxia. Balancing the risks of hypoxia and hyperoxia is especially critical in neonates, who are at increased risk for retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and mortality. Although studies on ORi in pediatric populations remain limited, it may support an individualized approach to defining safe oxygenation thresholds [

23]. However, because ORi is not equivalent to PaO

2, arterial blood gas analysis remains necessary to determine the optimal oxygen concentration [

24].

Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) facilitate tracheal intubation and immobility during pediatric anesthesia; however, inadequate reversal or excessive blockade can result in serious complications, including respiratory failure and aspiration pneumonia [

25,

26]. Therefore, neuromuscular monitoring (NMM) is crucial for assessing the degree of neuromuscular blockade in pediatric patients. NMM is essential for maintaining an appropriate depth of blockade during anesthesia, ensuring timely recovery after surgery, and minimizing postoperative complications.

NMM methods include clinical observation, qualitative assessment (nerve stimulator), and quantitative assessment techniques such as electromyography, mechanomyography, acceleromyography (AMG), and kinemyography. Among these, the train-of-four (TOF) stimulation method is the most widely used standard. TOF evaluates the depth of blockade and recovery by measuring muscle responses to 4 consecutive stimuli, and a TOF ratio ≥0.9 is generally considered indicative of sufficient recovery. In pediatric patients, NMM poses unique challenges due to anatomical and physiological differences, as well as variable drug responses. The absence of standardized guidelines, limited availability of monitoring equipment, inadequate user proficiency, and concerns about device reliability have contributed to the inconsistent application of NMM in clinical practice [

27]. Nevertheless, to prevent postoperative respiratory complications caused by residual neuromuscular blockade, quantitative NMM and documentation of TOF are essential whenever nondepolarizing muscle relaxants are administered. The consistent use of practical monitoring tools that can be easily applied and interpreted by clinicians is also critical [

28].

Accurate skin preparation, proper electrode placement, and the use of appropriately sized and spaced electrodes are vital for improving the accuracy of pediatric NMM. The cathode should be positioned distally, and electrode spacing should be adjusted in consideration of children’s smaller arm size and shorter nerve distances. The arm should be stabilized to prevent unnecessary movement, and baseline calibration (before NMBA administration) should be performed [

26,

29]. Because temperature changes can alter NMBA pharmacodynamics, maintaining a core temperature above 35°C and a peripheral temperature above 32°C is recommended [

30]. When using AMG, normalization of the TOF ratio after calibration is required, and applying a 5-second, 50 Hz tetanic stimulation before measurement can help stabilize the signal [

31].

Temperature monitoring is an essential perioperative parameter, enabling the detection of both hypothermia and hyperthermia, each of which requires prompt intervention. Intraoperative hypothermia occurs in approximately 50% of pediatric patients [

32,

33], and the incidence in neonates has been reported to exceed 80% [

34]. Children are more susceptible to heat loss because their thermoregulatory capacity is less effective than that of adults, their weight-to-surface-area ratio is lower, heat loss from the head is greater, and subcutaneous fat stores that provide thermal insulation are limited [

35]. Moreover, hypothermia can cause numerous adverse effects, including altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (particularly of NMBAs), impaired platelet function, coagulation abnormalities, increased bleeding tendency, cardiocirculatory and respiratory complications, delayed wound healing, and an elevated risk of surgical site infection [

36]. Accordingly, accurate temperature measurement is essential for appropriate intraoperative temperature management.

Because extremity and skin temperatures are typically lower than core body temperature [

37,

38], the esophagus is most commonly used for core temperature monitoring [

39]. Although the pulmonary artery provides the most accurate single-site core temperature measurement, it is highly invasive and thus unsuitable for non-cardiac surgical patients [

40]. Correct placement of an esophageal temperature probe between the left atrium and the descending aorta minimizes exposure to airway cooling and allows for accurate measurement of core temperature. In pediatric patients, insertion depth can be estimated using formulas such as that proposed by Hong et al. [

41] (height/5+5 cm from the incisors), which assists in determining the appropriate probe depth for accurate temperature assessment.

Airway management: from intubation to extubation

Efficiency of intubation techniques

Airway management in infants and young children is particularly challenging because of their anatomical and physiological differences from adults. In children, the larynx is positioned more anteriorly and superiorly, forming a sharper angle between the larynx and tongue during tracheal intubation. In addition, a proportionally larger tongue further limits endotracheal tube manipulation [

42,

43]. Recently, the use of video laryngoscopes (VLs) in pediatric anesthesia has increased, and multiple studies have examined their efficacy. VLs enable direct or indirect visualization of airway structures without requiring alignment of the oral, pharyngeal, and tracheal axes, thereby providing higher glottic exposure scores and reducing the need for airway manipulation during intubation [

44]. Furthermore, in less experienced users, VLs have been shown to improve first-attempt success rates compared to direct laryngoscopes (88% vs. 63%) [

45]. Rahendra et al. [

43] compared the effectiveness of spiral endotracheal tubes (spiral ETTs) with standard endotracheal tubes during intubation using a McGrath VL in children aged 1 month to 6 years. Although no significant differences were observed in total intubation time or first-attempt success rates, the spiral ETT achieved significantly shorter total tube handling time and greater accuracy in central positioning of the tube tip at the glottic opening compared with the standard ETT. However, when VLs were compared with direct laryngoscopy for routine tracheal intubation, intubation times and numbers of attempts were similar; thus, current evidence remains insufficient to either recommend or discourage the use of VLs for neonatal intubation [

46].

Extubation poses a substantial risk of complications in both adults and children; however, in pediatric patients, adverse respiratory events such as airway obstruction, laryngospasm, and oxygen desaturation occur more frequently [

47]. Tham and Lim [

48] reported that early extubation after pediatric cardiac surgery is feasible and associated with shorter intensive care unit stays and fewer mechanical ventilation–related complications. Nevertheless, in patients with pulmonary hypertension, impaired cardiac function, or a high risk of intraoperative bleeding, early extubation should be approached cautiously.

Post-extubation airway complications in children are primarily respiratory in nature. Laryngospasm, in particular, is associated with risk factors such as younger age, recent upper respiratory tract infection, and asthma. It may be triggered by laryngeal stimulation from the endotracheal tube, airway manipulation, secretions, or blood. Because pediatric airways are structurally delicate and highly sensitive to stimulation, 2 principal approaches are used for tube removal: deep extubation, performed under a deep plane of anesthesia, and awake extubation, performed when the patient is fully conscious. Although many pediatric anesthesiologists prefer awake extubation, studies have shown no significant difference in the incidence of serious complications between the 2 techniques [

49,

50]. Therefore, the choice of method should be based on the patient’s condition and the anesthesiologist’s experience. Deep extubation is often selected for patients with recent upper respiratory infections, asthma, or when postoperative coughing could be detrimental. Conversely, awake extubation is generally recommended for patients with a potentially difficult airway or a high likelihood of requiring reintubation.

According to Igarashi [

47], the timing of airway removal at the conclusion of surgery should take into account the patient’s respiratory and circulatory status, type of surgery, and risk of airway edema. The most critical consideration is the accurate assessment of anesthetic depth and the patient’s ability to maintain airway patency at the time of extubation. However, owing to the wide variation in age and physiological condition among pediatric patients, establishing standardized objective criteria remains difficult, and current practice primarily depends on clinical judgment and observation. Some studies have proposed awake extubation criteria—including facial grimacing, eye opening, purposeful movement, and adequate tidal volume—but no definitive criteria exist for deep extubation [

3]. The laryngeal stimulation test provides an objective means of assessing anesthetic depth before extubation. It involves gently moving the endotracheal tube and observing the laryngeal response. In stage 1 (awake), stimulation elicits coughing and brief apnea; in stage 2 (light anesthesia), it produces repetitive coughing and apnea lasting longer than 5 seconds, during which the risk of laryngospasm is high; and in stage 3 (deep anesthesia), there is no response to stimulation [

51].

Expanding the horizons

Transfontanelle ultrasound

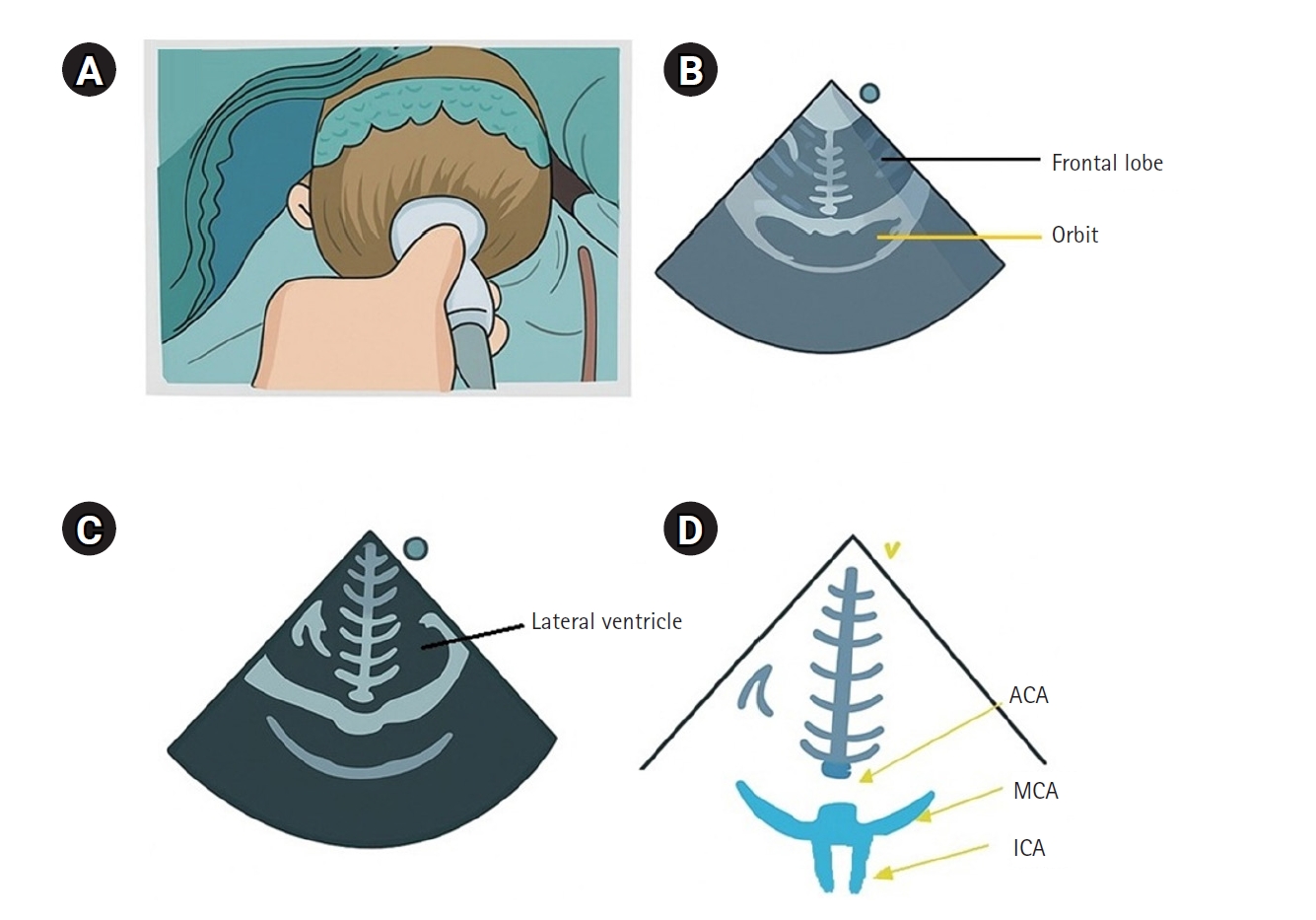

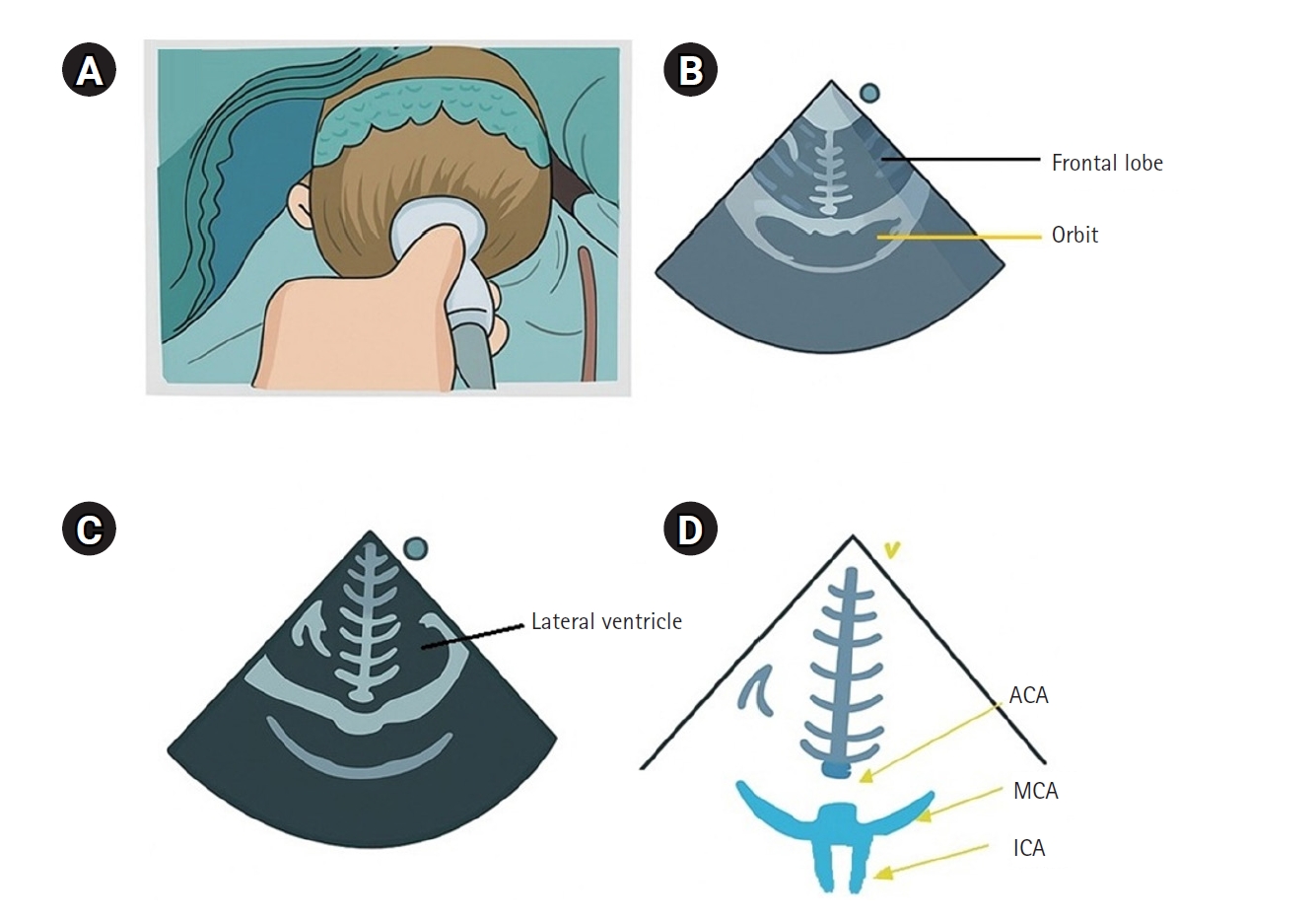

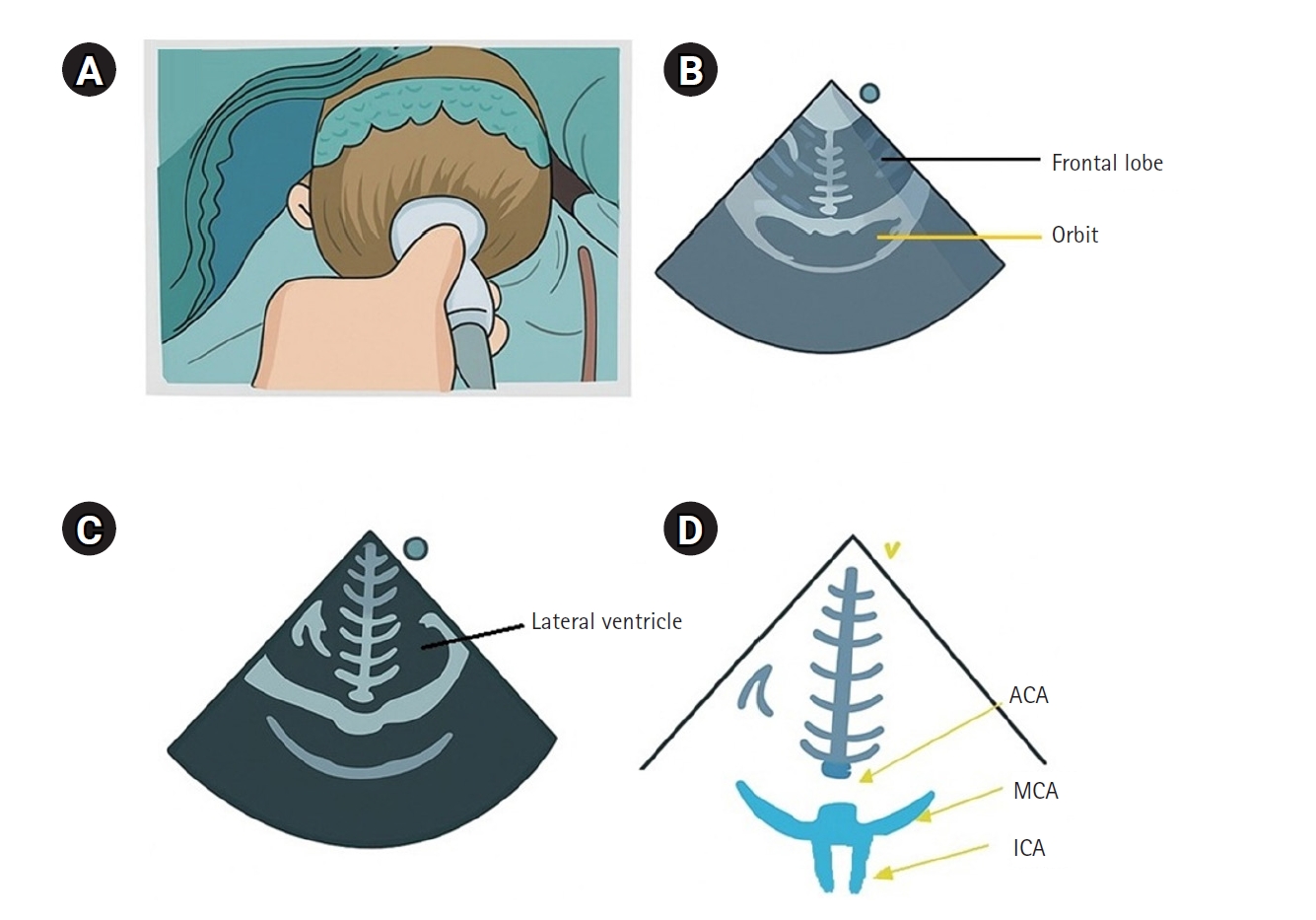

Cerebral blood flow velocity can be assessed using transcranial Doppler; however, in pediatric patients, the small size of cerebral vessels makes it difficult to maintain proper probe positioning, thereby limiting its clinical application. In contrast, transfontanelle ultrasonography (TFU) enables the evaluation of blood flow in major cerebral vessels using standard ultrasound equipment and probes, making it particularly valuable in children (

Fig. 1). TFU allows real-time visualization of key intracranial anatomical structures, including the ventricles, cerebral arteries, and overall cerebral circulation, while also providing hemodynamic parameters such as blood flow velocity and resistance indices [

52]. TFU has been employed for real-time monitoring of cerebral blood flow during cardiac and neurosurgical procedures, enabling the assessment of hemodynamic changes before and after surgery and throughout cardiopulmonary bypass [

53]. It also aids in detecting intraoperative abnormalities such as flow reversal or vascular occlusion. When TFU indicates decreased cerebral blood flow during surgery, it can be combined with near-infrared spectroscopy to confirm cerebral perfusion status. This multimodal approach is especially critical in neonates and infants who are at high risk of brain injury. Overall, TFU provides a noninvasive, real-time means of assessing cerebral blood flow in pediatric surgical patients. However, further studies are needed to expand its clinical applications and to establish standardized protocols for its routine use [

52].

In neonates and infants, general anesthesia carries a higher risk of adverse effects such as hypoxemia, bradycardia, and postoperative apnea. Because hepatic and renal functions are immature, drug metabolism is delayed, potentially prolonging anesthetic effects. Furthermore, concerns have been raised regarding the possible long-term impact of general anesthesia on neurodevelopment. Regional anesthesia (RA) reduces the need for general anesthetics and systemic analgesics, thereby promoting faster recovery and improving postoperative safety [

54].

Safe administration of RA requires continuous monitoring, precise drug dosing, and accurate injection techniques. Among central neuraxial blocks, caudal epidural anesthesia is the most frequently performed and can be guided by anatomical landmarks, nerve stimulators, or ultrasound, of which ultrasound guidance significantly enhances the accuracy of catheter placement. Bupivacaine (0.25%) is the most commonly used local anesthetic, with dosage adjusted according to the surgical site (

Table 1) [

55]. In neonates, the needle insertion depth beyond the sacrococcygeal membrane should be limited based on body weight to prevent injury. When an indwelling catheter is placed, its position should be confirmed and carefully managed throughout the procedure. Adherence to these technical precautions ensures safe and effective anesthesia in neonates and infants. Peripheral nerve blocks are widely used in both upper- and lower-limb surgeries and are typically performed under ultrasound guidance to increase precision and safety. For upper limbs, the supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary approaches are most commonly employed, whereas femoral and sciatic nerve blocks are standard for lower-limb procedures. Although RA offers numerous benefits, Ponde et al. emphasized the importance of recognizing and managing local anesthetic systemic toxicity, integrating multimodal analgesia before and after surgery, maintaining vigilant monitoring, fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, and providing thorough explanations to parents [

56].

Conclusion

Pediatric anesthesia requires individualized approaches that reflect the unique physiological and anatomical characteristics of children. Optimization of oxygen delivery, precise monitoring of neuromuscular blockade and temperature, and individualized airway management are essential to minimize perioperative risks. Emerging modalities such as TFU enhance cerebral monitoring, while RA offers an effective alternative to general anesthesia, potentially reducing neurodevelopmental risks. Despite these advancements, challenges persist in standardizing practices and training due to patient variability and declining pediatric case volumes. Ongoing research, education, and multidisciplinary collaboration remain essential to further improve the safety and efficacy of pediatric anesthesia care.

-

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: HYK. Data curation: HYK. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: HYK. Project administration: HYK. Funding acquisition: HYK. Writing–original draft: HYK. Writing–review & editing: HYK.

-

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Funding

None.

-

Data availability

Not applicable.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

-

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Coronal section of transfontanelle ultrasonography. (A) Probe placement on the anterior fontanelle of the infant, (B) coronal frontal image, (C) coronal image at Monro levels, and (D) coronal sections of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), middle cerebral artery (MCA), and both internal carotid arteries (ICAs).

Table 1.Dosages of various common local anesthetics

|

Bupivacaine |

Ropivacaine |

Levobupivacaine |

Lidocaine with adrenaline |

|

Allowable dose (mg/kg) |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

7 |

|

Bolus for peripheral and truncal blocks (mL/kg) |

0.25 |

0.2 |

0.25 |

0.125 |

|

For infusion concentration (%) |

0.2 or 0.1 |

0.2 or 0.1 |

0.2 or 0.1 |

0.2 or 0.1 |

|

For infusion rate (mg/kg/hr) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

- |

References

- 1. Time to be serious about children’s health care. Lancet 2001;358:431. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05606-9

- 2. Macfarlane F. Paediatric anatomy and physiology and the basics of paediatric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia UK; 2006.

- 3. Gaba DM. Anaesthesiology as a model for patient safety in health care. BMJ 2000;320:785-788. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.785

- 4. Modell JH. Assessing the past and shaping the future of anesthesiology: the 43rd Rovenstine Lecture. Anesthesiology 2005;102:1050-1057. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200505000-00025

- 5. Cho SA, Lee JH, Ji SH, Jang YE, Kim EH, Kim HS, Kim JT. Critical incidents associated with pediatric anesthesia: changes over 6 years at a tertiary children’s hospital. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2022;17:386-396. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.22164

- 6. Vandermotten C, Dessouroux C. Mapping the massive global fertility decline over the last 20 years. Popul Soc 2024;618:1-4. https://doi.org/10.3917/popsoc.618.0001

- 7. Lee GT, Ju SH, Choi YC, Lee SY. Determinants of fertility through machine learning and time series analysis and response to low birth crisis. Korean Local Adm Rev 2025;22:1-21. https://doi.org/10.32427/klar.2025.22.1.1

- 8. Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, O’Sullivan EP, Woodall NM, Ahmad I. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth 2015;115:827-848. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev371

- 9. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, Fiadjoe JE, Greif R, Klock PA, Mercier D, Myatra SN, O’Sullivan EP, Rosenblatt WH, Sorbello M, Tung A. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology 2022;136:31-81. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004002

- 10. Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, Drolet P, Duggan LV, Griesdale DE, Hung OR, Jones PM, Kovacs G, Massey S, Morris IR, Mullen T, Murphy MF, Preston R, Naik VN, Scott J, Stacey S, Turkstra TP, Wong DT. The difficult airway with recommendations for management: part 2--the anticipated difficult airway. Can J Anaesth 2013;60:1119-1138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-013-0020-x

- 11. Fridovich I. Oxygen toxicity: a radical explanation. J Exp Biol 1998;201:1203-1209. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.201.8.1203

- 12. Winslow RM. Oxygen: the poison is in the dose. Transfusion 2013;53:424-437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03774.x

- 13. Freeman BA, Crapo JD. Hyperoxia increases oxygen radical production in rat lungs and lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem 1981;256:10986-10992. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)68544-3

- 14. Cho SA. What is your optimal target of oxygen during general anesthesia in pediatric patients? Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S5-S11. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23103

- 15. O’Brien J. Absorption atelectasis: incidence and clinical implications. AANA J 2013;81:205-208.

- 16. Green S, Stuart D. Oxygen therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: we need to rethink and investigate. Respirology 2020;25:470-471. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13797

- 17. Mitra S, Altit G. Inhaled nitric oxide use in newborns. Paediatr Child Health 2023;28:119-127. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxac107

- 18. Habre W, Petak F. Perioperative use of oxygen: variabilities across age. Br J Anaesth 2014;113 Suppl 2:ii26-ii36. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu380

- 19. Perrone S, Tataranno ML, Buonocore G. Oxidative stress and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Clin Neonatol 2012;1:109-114. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4847.101683

- 20. Philip AG. Oxygen plus pressure plus time: the etiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics 1975;55:44-50. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.55.1.44

- 21. Hartnett ME, Lane RH. Effects of oxygen on the development and severity of retinopathy of prematurity. J AAPOS 2013;17:229-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.12.155

- 22. Pedersen T, Nicholson A, Hovhannisyan K, Moller AM, Smith AF, Lewis SR. Pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD002013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002013.pub3

- 23. Liz CF, Proenca E. Oxygen in the newborn period: could the oxygen reserve index offer a new perspective? Pediatr Pulmonol 2025;60:e27343. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.27343

- 24. Scheeren TW, Belda FJ, Perel A. The oxygen reserve index (ORI): a new tool to monitor oxygen therapy. J Clin Monit Comput 2018;32:379-389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-017-0049-4

- 25. Klucka J, Kosinova M, Krikava I, Stoudek R, Toukalkova M, Stourac P. Residual neuromuscular block in paediatric anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2019;122:e1-e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.10.001

- 26. Cammu G, De Witte J, De Veylder J, Byttebier G, Vandeput D, Foubert L, Vandenbroucke G, Deloof T. Postoperative residual paralysis in outpatients versus inpatients. Anesth Analg 2006;102:426-429. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000195543.61123.1f

- 27. Thilen SR, Weigel WA, Todd MM, Dutton RP, Lien CA, Grant SA, Szokol JW, Eriksson LI, Yaster M, Grant MD, Agarkar M, Marbella AM, Blanck JF, Domino KB. 2023 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for monitoring and antagonism of neuromuscular blockade: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Neuromuscular Blockade. Anesthesiology 2023;138:13-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004379

- 28. Ozgen ZS. Neuromuscular blockade monitoring in pediatric patients. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S12-S24. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23158

- 29. Zhou ZJ, Wang X, Zheng S, Zhang XF. The characteristics of the staircase phenomenon during the period of twitch stabilization in infants in TOF mode. Paediatr Anaesth 2013;23:322-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12041

- 30. Rodney G, Raju P, Brull SJ. Neuromuscular block management: evidence-based principles and practice. BJA Educ 2024;24:13-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2023.10.005

- 31. Renew JR, Hernandez-Torres V, Logvinov I, Nemes R, Nagy G, Li Z, Watt L, Murphy GS. Comparison of the TetraGraph and TOFscan for monitoring recovery from neuromuscular blockade in the post anesthesia care unit. J Clin Anesth 2021;71:110234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110234

- 32. Pearce B, Christensen R, Voepel-Lewis T. Perioperative hypothermia in the pediatric population: prevalence, risk factors and outcomes. J Anesth Clin Res 2010;1:1000102. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6148.1000102

- 33. Gorges M, Afshar K, West N, Pi S, Bedford J, Whyte SD. Integrating intraoperative physiology data into outcome analysis for the ACS Pediatric National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Paediatr Anaesth 2019;29:27-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13531

- 34. Cui Y, Wang Y, Cao R, Li G, Deng L, Li J. The low fresh gas flow anesthesia and hypothermia in neonates undergoing digestive surgeries: a retrospective before-after study. BMC Anesthesiol 2020;20:223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-020-01140-5

- 35. Galante D. Intraoperative hypothermia: relation between general and regional anesthesia, upper- and lower-body warming: what strategies in pediatric anesthesia? Paediatr Anaesth 2007;17:821-823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02248.x

- 36. Mullany LC, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch JM. Risk of mortality associated with neonatal hypothermia in southern Nepal. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:650-656. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.103

- 37. Burgess GE III, Cooper J, Marino R, Peuler M. Continuous monitoring of skin temperature using a liquid-crystal thermometer during anesthesia. Surv Anesthesiol 1979;23:176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00132586-197906000-00031

- 38. Rubinstein EH, Sessler DI. Skin-surface temperature gradients correlate with fingertip blood flow in humans. Anesthesiology 1990;73:541-545. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199009000-00027

- 39. Bloch EC, Ginsberg B, Binner RA. The esophageal temperature gradient in anesthetized children. J Clin Monit 1993;9:73-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01616917

- 40. Sessler DI. Perioperative temperature monitoring. Anesthesiology 2021;134:111-118. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003481

- 41. Hong SH, Lee J, Jung JY, Shim JW, Jung HS. Simple calculation of the optimal insertion depth of esophageal temperature probes in children. J Clin Monit Comput 2020;34:353-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-019-00327-7

- 42. Lillie EM, Harding L, Thomas M. A new twist in the pediatric difficult airway. Paediatr Anaesth 2015;25:428-430. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12538

- 43. Rahendra R, Sesario F, Ramlan AA, Zahra R, Kapuangan C, Marsaban AH, Perdana A. Endotracheal intubation using a spiral endotracheal tube effectively reduces total tube handling time in children aged one month to six years using a McGrathTM video laryngoscope: a prospective randomized trial. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S113-S120. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.24018

- 44. Jagannathan N, Hajduk J, Sohn L, Huang A, Sawardekar A, Albers B, Bienia S, De Oliveira GS. Randomized equivalence trial of the King Vision aBlade videolaryngoscope with the Miller direct laryngoscope for routine tracheal intubation in children <2 yr of age. Br J Anaesth 2017;118:932-937. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex073

- 45. Parmekar S, Arnold JL, Anselmo C, Pammi M, Hagan J, Fernandes CJ, Lingappan K. Mind the gap: can videolaryngoscopy bridge the competency gap in neonatal endotracheal intubation among pediatric trainees?: a randomized controlled study. J Perinatol 2017;37:979-983. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.72

- 46. Lingappan K, Arnold JL, Fernandes CJ, Pammi M. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;6:CD009975. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009975.pub3

- 47. Igarashi A. Extubation and removal of supraglottic airway devices in pediatric anesthesia. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S49-S60. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.24006

- 48. Tham SQ, Lim EH. Early extubation after pediatric cardiac surgery. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S61-S72. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23154

- 49. von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Davies K, Hegarty M, Erb TO, Habre W. The effect of deep vs. awake extubation on respiratory complications in high-risk children undergoing adenotonsillectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013;30:529-536. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835df608

- 50. Baijal RG, Bidani SA, Minard CG, Watcha MF. Perioperative respiratory complications following awake and deep extubation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth 2015;25:392-399. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12561

- 51. Templeton TW, Goenaga-Diaz EJ, Downard MG, McLouth CJ, Smith TE, Templeton LB, Pecorella SH, Hammon DE, O’Brien JJ, McLaughlin DH, Lawrence AE, Tennant PR, Ririe DG. Assessment of common criteria for awake extubation in infants and young children. Anesthesiology 2019;131:801-808. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002870

- 52. Kim EH, Park JB, Kim JT. Intraoperative transfontanelle ultrasonography for pediatric patients. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S25-S35. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.24106

- 53. Robba C, Taccone FS. How I use transcranial Doppler. Crit Care 2019;23:420. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2700-6

- 54. Davidson AJ, Morton NS, Arnup SJ, de Graaff JC, Disma N, Withington DE, Frawley G, Hunt RW, Hardy P, Khotcholava M, von Ungern Sternberg BS, Wilton N, Tuo P, Salvo I, Ormond G, Stargatt R, Locatelli BG, McCann ME; General Anesthesia compared to Spinal anesthesia (GAS) Consortium. Apnea after awake regional and general anesthesia in infants: the general anesthesia compared to spinal anesthesia study: comparing apnea and neurodevelopmental outcomes, a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2015;123:38-54. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000709

- 55. Ponde V. Recent trends in paediatric regional anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth 2019;63:746-753. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_502_19

- 56. Ponde VC, Rath A, Singh N. Expert’s tips on regional blocks in neonates and infants. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:S73-S86. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23164