Abstract

-

Objectives:

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the first seasonal influenza epidemic was

declared in the 37th week of 2022 in Korea and has continued through the

winter of 2023–2024. However, this finding has not been observed in

the United States and Europe. The present study aimed to determine whether

the prolonged influenza epidemic in Korea from 2022 to 2023 was caused by

using a different influenza epidemic threshold compared to the thresholds

used in the United States and Europe.

-

Methods:

Korea, the United States, and Europe use different methods to set seasonal

influenza epidemic thresholds. First, we calculated the influenza epidemic

thresholds for influenza seasons using the different methods of those three

regions. Using these epidemic thresholds, we then compared the duration of

influenza epidemics for the most recent three influenza seasons.

-

Results:

The epidemic thresholds estimated by the Korean method were lower than those

by the other methods, and the epidemic periods defined using the Korean

threshold were estimated to be longer than those defined by the other

regions’ thresholds.

-

Conclusion:

A low influenza epidemic threshold may have contributed to the prolonged

influenza epidemic in Korea, which was declared in 2022 and has continued

until late 2023. A more reliable epidemic threshold for seasonal influenza

surveillance needs to be established in Korea.

-

Keywords: Influenza; human; Sentinel surveillance; Epidemics; Seasons

Introduction

Background

Influenza is a communicable disease primarily caused by influenza A or B viruses.

It is a common acute respiratory illness that tends to spread during the winter

season in Korea. Transmission occurs through respiratory droplets emitted from

infected subjects. The basic reproduction number, which is defined as the

average number of secondary cases per case in a totally susceptible population,

has been observed to range from 1.27 to 1.8 in the four pandemics since the 20th

century and during seasonal influenza epidemics [

1]. Influenza poses a high risk of complications and can result in

serious clinical outcomes in vulnerable populations, such as those aged 65 and

above, children, and people with chronic diseases. It also increases absenteeism

rates at workplaces and schools, and rapidly increases the demand for medical

care, significantly impacting society from a public health perspective.

Influenza surveillance involves collecting data on influenza transmission trends

and circulating virus types to predict the timing and intensity of epidemics.

Surveillance helps maintain an appropriate level of preparedness, with the goal

of minimizing the socioeconomic impact during the influenza season. In Korea,

surveillance measures include monitoring outpatient illness, hospitalizations,

and virological factors to determine the onset and end of epidemics, analyze

their progression, and manage seasonal influenza based on pathogen

characteristics. Outpatient illness surveillance is carried out at approximately

200 sentinel sites nationwide as of October 2023, with 87 of these sites also

participating in virological surveillance. Additionally, influenza

hospitalizations and deaths are surveilled at secondary and tertiary hospitals

to monitor the severity of seasonal influenza [

2].

In Korea and the United States (U.S.), influenza surveillance among outpatients

collects information on influenza-like illness (ILI). The proportion of visits

with ILI among all outpatient visits is estimated and used as a monitoring tool

for influenza surveillance [

2,

3]. While the case definition of ILI varies

across countries and agencies, it generally consists of fever and respiratory

infection symptoms. Since ILI is a common clinical presentation of various

respiratory infections, it is used as a surrogate indicator for tracking

influenza epidemics even though it does not accurately estimate the incidence of

influenza [

4,

5]. The positivity rate of respiratory specimens for

influenza viruses is also used as a monitoring indicator, with the European

Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) defining the start and end of

influenza epidemics based on a 10% positivity rate in respiratory samples

collected from sentinel sites [

6].

In Korea, unlike the U.S. and Europe, an influenza alert that was issued in the

37th week of 2022 has been in effect for 69 consecutive weeks as of December

2023 [

7]. This is the first occurrence of

such a phenomenon since the establishment of the influenza surveillance system

in Korea in 2000. It also deviates from the well-known epidemiological

characteristic that influenza typically spreads in the winter season in

temperate regions [

8–

10]. Therefore, a rigorous assessment is

necessary to determine whether this phenomenon can be interpreted as reflecting

an actual prolonged increase in influenza activity.

This study aimed to compare the duration of seasonal influenza epidemics

calculated using different influenza epidemic thresholds used in Korea, the

U.S., and Europe. The implications of the study findings will be discussed in

the context of the ongoing influenza epidemic in Korea that has lasted since

2022.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was based on public data. Neither approval by the institutional review

board nor obtainment of informed consent was required.

Study design

This was a comparative study.

Setting

The epidemic periods for the three most recent seasons (2018–2019,

2019–2020, 2022–2023) were analyzed, excluding the two seasons

(2020–2021, 2021–2022) that did not experience influenza

epidemics. This analysis applied the epidemic thresholds established by Korea,

the U.S., and Europe.

Data sources and measurement

National influenza surveillance data in Korea were collected from the weekly

reports published by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA)

[

11]. Weekly data on ILI rates, the

number of respiratory specimens, and the number of influenza-positive specimens

from the 36th week of 2015 to the 35th week of 2023 were used. In Korea, ILI is

defined as the presence of fever of 38℃ or higher and respiratory

infection symptoms, such as cough and sore throat. Accordingly, this study

applied the Korean ILI definition to data to estimate the epidemic threshold for

Korea using the Korean and the U.S. methods [

2]. Data from the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 seasons were

excluded from the analysis, as there was no influenza outbreak during these

seasons. The influenza season was defined as the period from the 36th week of

each year to the 35th week of the following year. Each week was defined as

starting on Sunday and ending on Saturday. For a week that spanned two years,

the week number was assigned based on the year in which the Sunday fell.

The influenza epidemic thresholds from the KDCA, the U.S. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC), and the ECDC were chosen for a comparative

analysis. Korea and the U.S. use the sum of the mean and two standard deviations

of weekly ILI rates from non-influenza time periods as the epidemic threshold.

In Korea, data from the past 3 seasons are used for the calculation, whereas

data from the past 2 seasons are used in the U.S. [

2,

3]. Europe, in

contrast, uses a 10% influenza positivity rate in respiratory specimens as the

epidemic threshold (

Table 1) [

6]. For the Korean and U.S. methods, the

earlier of two consecutive weeks when the weekly ILI rate exceeds the epidemic

threshold is defined as the start of the influenza epidemic, and the week prior

to two consecutive weeks when the weekly ILI rate does not reach the epidemic

threshold is defined as the end of the epidemic. In the European method, the

epidemic period is determined based on the 10% influenza positivity rate.

Table 1.Epidemic thresholds for seasonal influenza

|

Country/region |

Epidemic threshold |

|

Korea (KDCA) |

-[Mean rate of ILI (per 1,000) during

non-influenza weeks for the most recent three

seasons+(2×SDs)]

-A non-influenza time period is

defined as two or more consecutive weeks in which influenza

positivity among respiratory laboratory samples is lower than

2% |

|

United States (CDC) |

-[Mean percentage of ILI during

non-influenza weeks for the most recent two

seasons+(2×SDs)]

-A non-influenza time period is

defined as two or more consecutive weeks in which each week

accounted for less than 2% of the season’s total number

of specimens that tested positive for influenza |

|

Europe (ECDC) |

-10% influenza positivity among

respiratory laboratory samples |

Bias

There was no bias in selecting target data.

Study size

There was no need to calculate the study size because known data were used.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

Epidemic trends in Korea according to the Korean influenza epidemic

threshold

In total, 312 weeks of data from six influenza seasons were collected from the

KDCA's weekly reports. Despite using the same influenza surveillance

data, differences were observed in the epidemic thresholds and the durations of

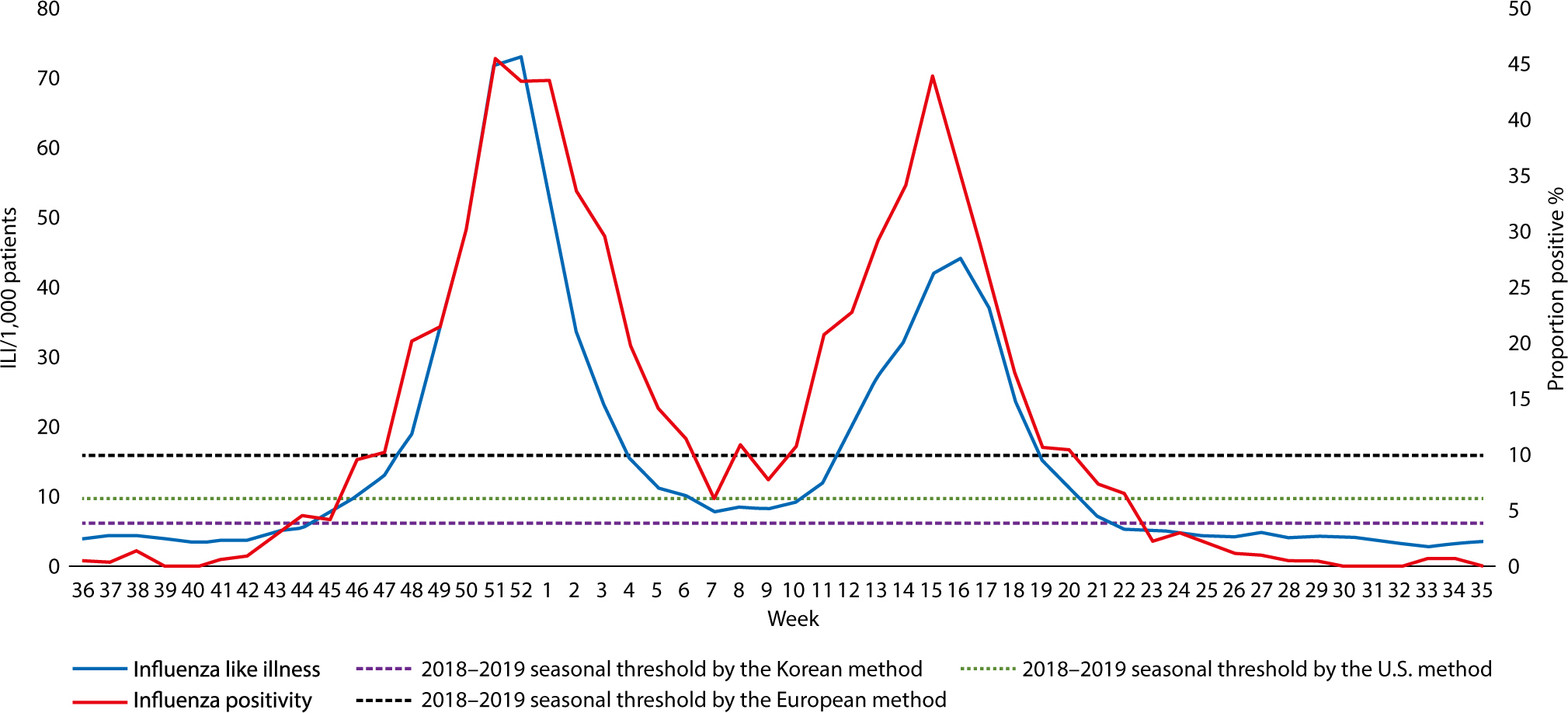

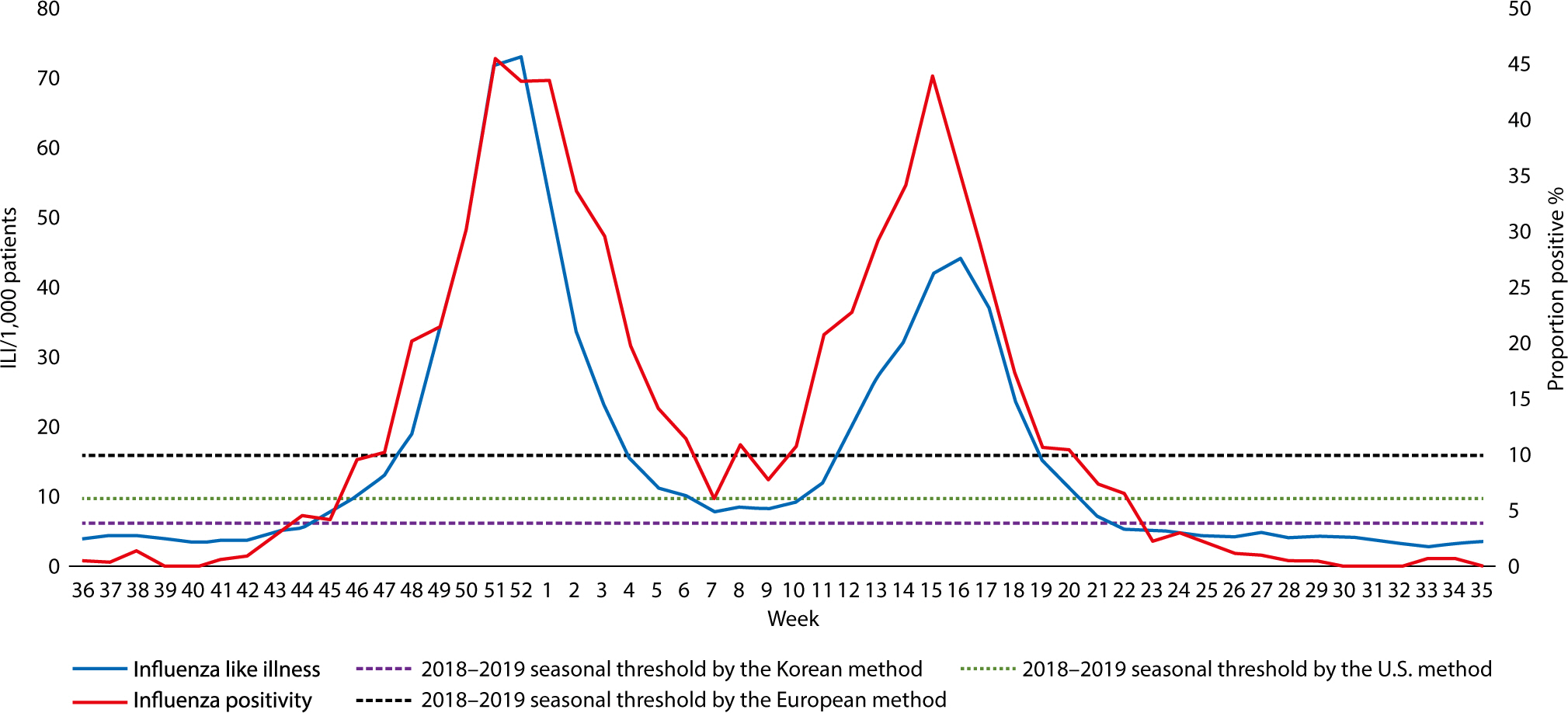

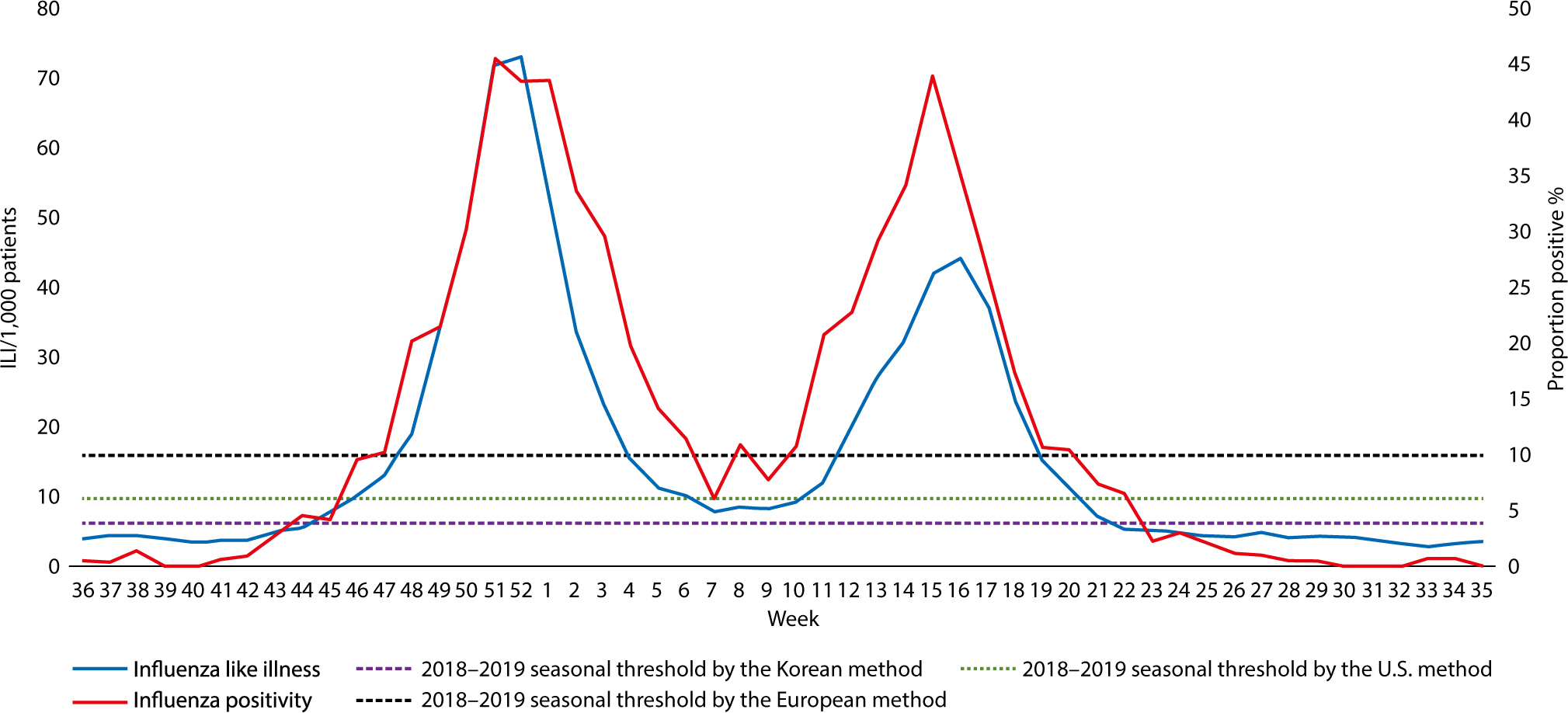

epidemics depending on the applied method. In the 2018–2019 season, two

influenza epidemic peaks were observed (

Fig.

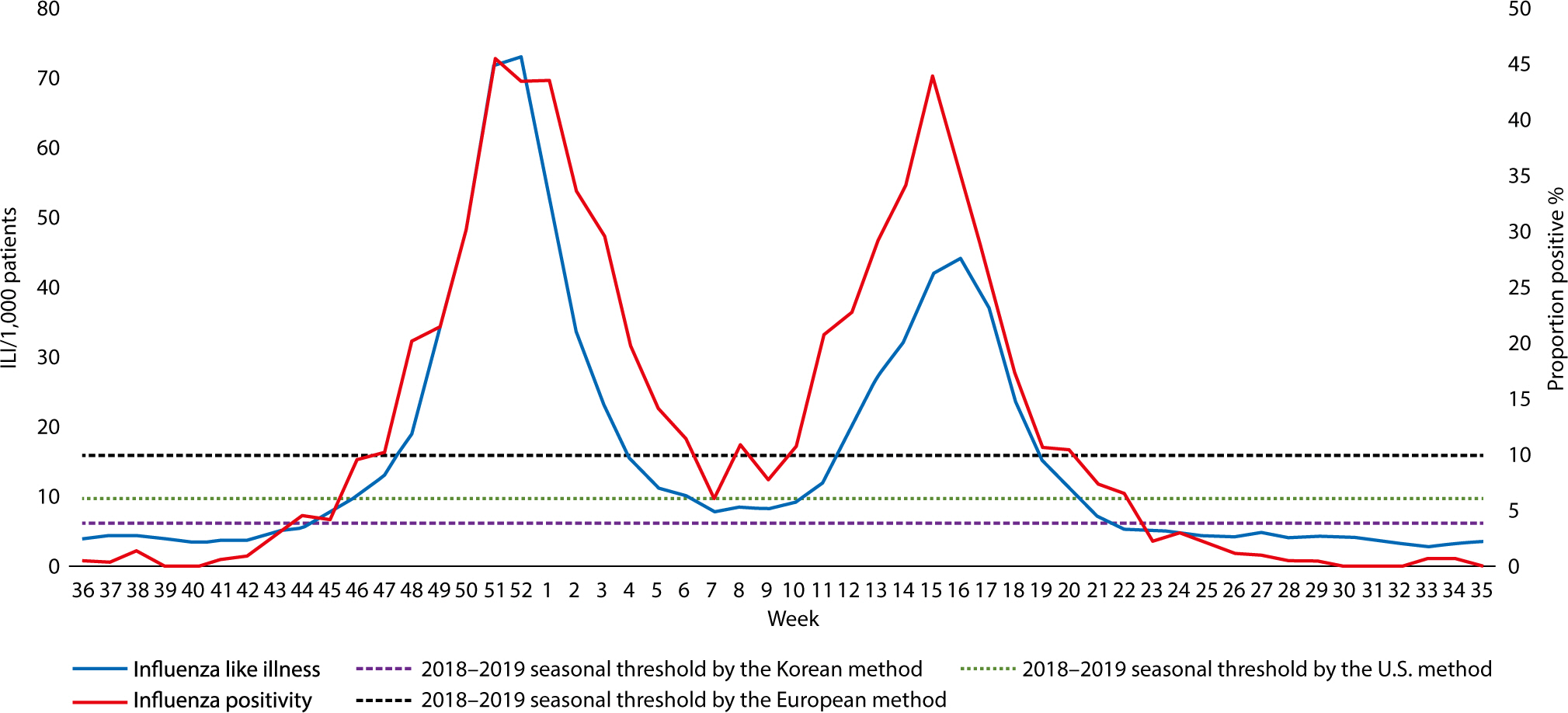

1, Dataset 1), and in the 2019–2020 season, the epidemic ended

early due to the measures taken in response to the emergence of severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with no spring outbreak

observed (

Fig. 2, Dataset 2). In the

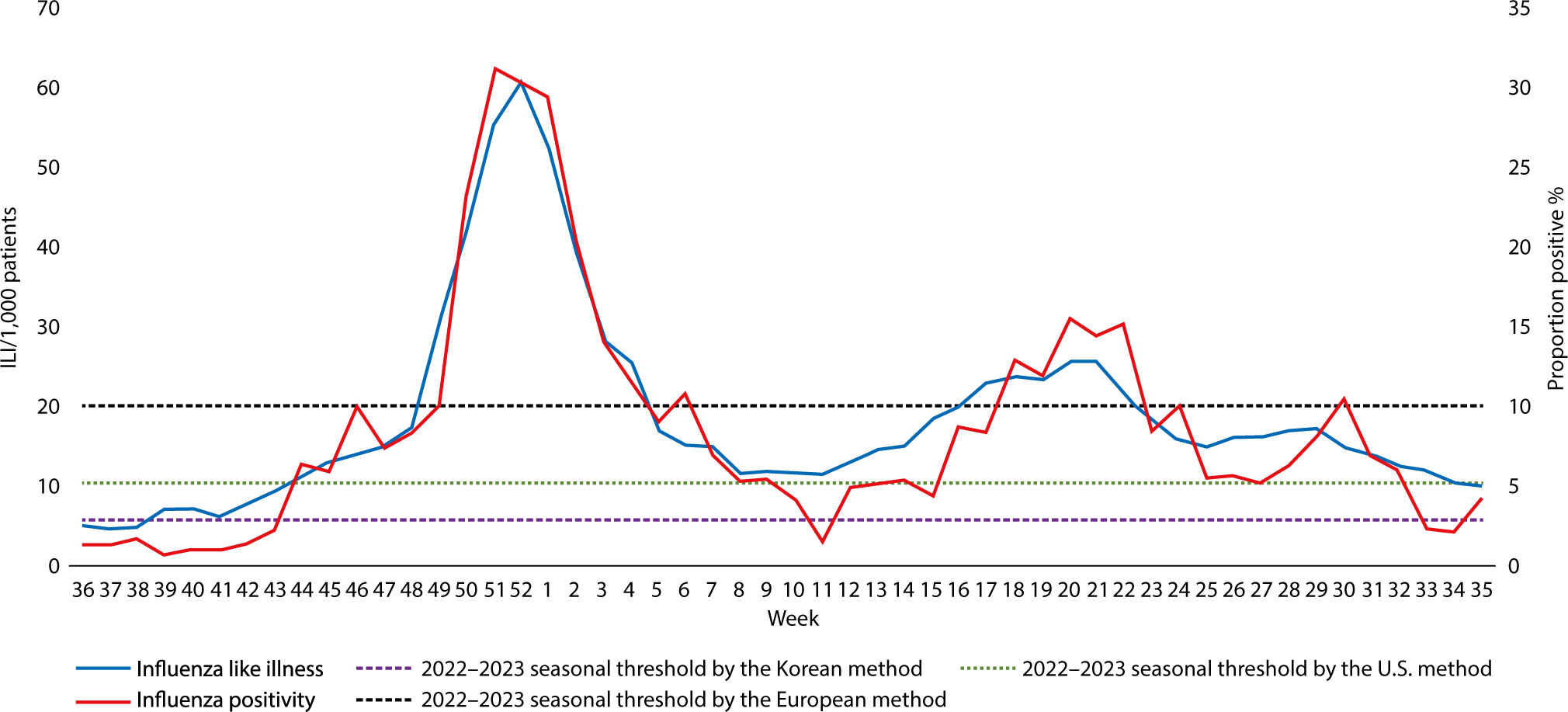

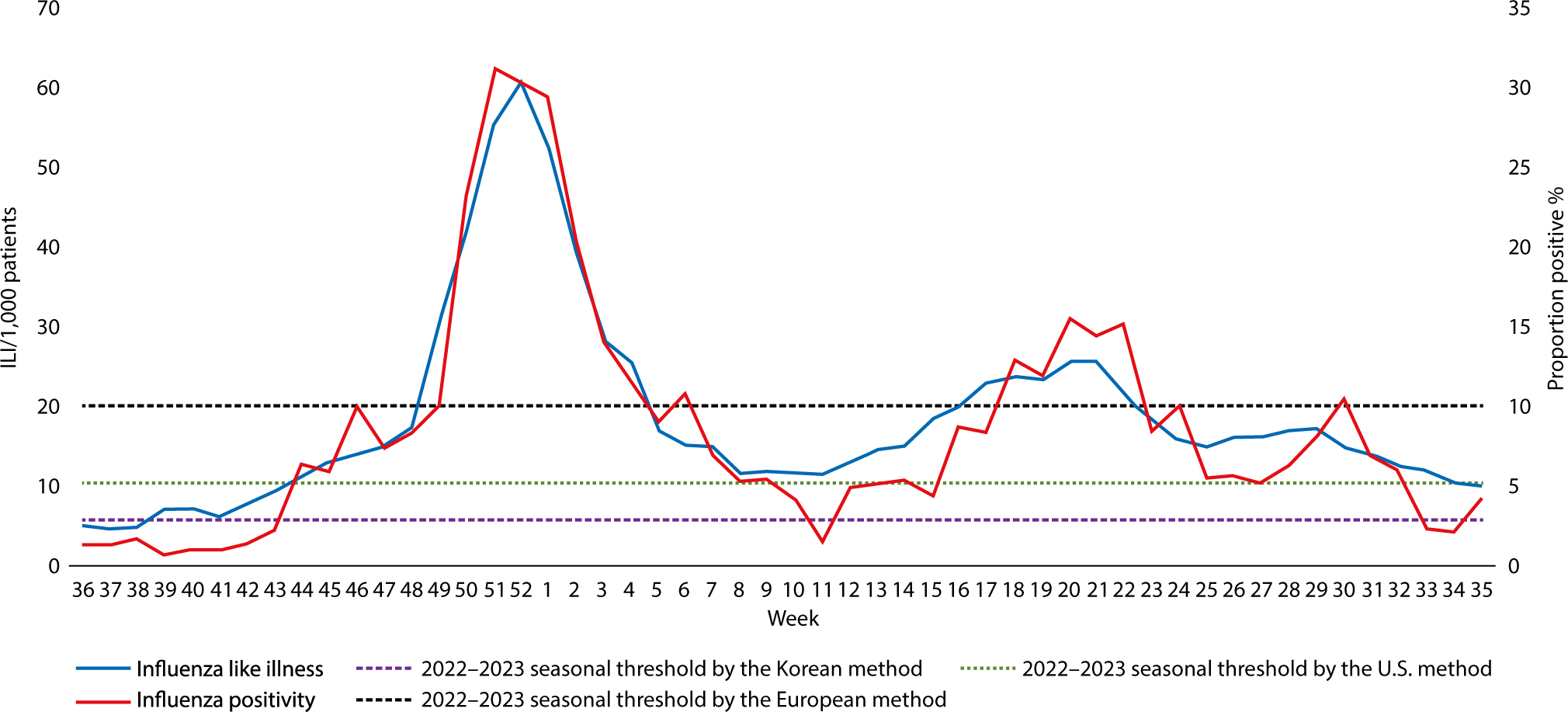

2022–2023 season, elevated ILI rates were observed in general (

Fig. 3, Dataset 3).

Fig. 1.2018−2019 season influenza activity. ILI, influenza-like

illness.

Fig. 2.2019−2020 season influenza activity. ILI, influenza-like

illness.

Fig. 3.2022−2023 season influenza activity. ILI, influenza-like

illness.

Non-influenza time periods

To calculate the epidemic threshold, the Korean method used ILI rates from

non-influenza periods in 156 weeks of the past 3 matching seasons, while the

U.S. method used ILI rates from non-influenza periods in 104 weeks of the past 2

matching seasons. For the Korean method, the non-influenza period for the

epidemic threshold calculations for the 2018–2019, 2019–2020, and

2022–2023 seasons comprised an average of 70.7 weeks (45.3%), while the

non-influenza period for the same seasons using the U.S. method was an average

of 74.7 weeks (71.8%). Since the non-influenza period defined by the Korean

method was shorter, lower ILI rates were used in the epidemic threshold

calculation than with the U.S. method. Accordingly, the mean and SD values

derived from the ILI rates for the non-influenza time periods used in the Korean

method were lower than those for the U.S. method (

Table 2).

Table 2.Characteristics of the influenza seasons used for epidemic threshold

calculation

|

Influenza season |

Korean method |

U.S. method |

|

Seasons used for the calculation

(length*) |

Length* of non-influenza period |

Mean rate of ILI during

non-influenza weeks |

SD of ILI during non-influenza

weeks |

Seasons used for the calculation

(length*) |

Length* of non-influenza period |

Mean rate of ILI during

non-influenza weeks |

SD of ILI during non-influenza

weeks |

|

2018−2019 |

2015−2016, 2016−2017,

2017−2018 (156) |

75 |

4.63 |

0.85 |

2016−2017, 2017−2018

(104) |

76 |

5.70 |

2.01 |

|

2019−2020 |

2016−2017, 2017−2018,

2018−2019 (156) |

64 |

4.38 |

0.79 |

2017−2018, 2018−2019

(104) |

74 |

5.87 |

2.62 |

|

2022−2023 |

2017−2018, 2018−2019,

2019−2020 (156) |

73 |

3.51 |

1.15 |

2018−2019, 2019−2020

(104) |

74 |

4.64 |

2.91 |

Influenza epidemic thresholds

The influenza epidemic thresholds estimated using the Korean method were 6.3 ILI

cases per 1,000 patients (2018–2019 season), 6.0 ILI cases per 1,000

patients (2019–2020 season), 5.8 ILI cases per 1,000 patients

(2022–2023 season), and 6.3 ILI cases per 1,000 patients

(2023–2024 season). The thresholds calculated using the U.S. method were

9.7 ILI cases per 1,000 patients (2018–2019 season), 11.1 ILI cases per

1,000 patients (2019–2020 season), 10.5 ILI cases per 1,000 patients

(2022–2023 season), and 18.7 ILI cases per 1,000 patients

(2023–2024 season). The Korean method yielded lower epidemic thresholds

than the U.S. method in all seasons. The largest difference was observed for the

2023–2024 season, which reflected the 2022–2023 season data during

the COVID-19 pandemic (

Table 3).

Table 3.Comparison of influenza epidemic thresholds according to different

methods

|

Season |

Threshold according to the Korean

method*

|

Threshold according to the U.S.

method*

|

European threshold |

|

2018−2019 |

6.3 |

9.7 |

10% influenza

positivity |

|

2019−2020 |

6.0 |

11.1 |

|

2022−2023 |

5.8 |

10.5 |

|

2023−2024 |

6.3 |

18.7 |

The epidemic period estimated using the thresholds of Korea, U.S., and

Europe

The estimated duration of the epidemic period using the Korean threshold was

longer than those calculated with the U.S. and European thresholds in all

seasons. The durations based on the Korean thresholds were 29 weeks

(2018–2019 season), 17 weeks (2019–2020 season), and 49 weeks

(2022–2023 season). In contrast, the durations based on the U.S.

thresholds were 23 weeks (2018–2019 season), 12 weeks (2019–2020

season), and 43 weeks (2022–2023 season). Durations calculated with the

European thresholds were the shortest, at 24 weeks (2018–2019 season), 13

weeks (2019–2020 season), and 16 weeks (2022–2023 season;

Table 4). The mean epidemic duration for

three seasons based on the Korean thresholds was 5.7 weeks (22%) longer per

season compared to that calculated using the U.S. method, and 14 weeks (79%)

longer compared to that calculated using the European method. The difference was

particularly prominent in the 2022–2023 season, where the duration based

on the Korean thresholds was 33 weeks longer than that based on the European

threshold.

Table 4.Comparison of epidemic period durations according to different

thresholds

|

Season |

Duration according to the Korean

threshold (weeks) |

Duration according to the U.S.

threshold (weeks) |

Duration according to the European

threshold (weeks) |

|

2018−2019 |

29 |

23 |

24 |

|

2019−2020 |

17 |

12 |

13 |

|

2022−2023 |

49 |

43 |

16 |

Discussion

Key results

This study compared the influenza epidemic periods in Korea during the

2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2022–2023 seasons, utilizing

epidemic thresholds from Korea, the U.S., and Europe. The influenza epidemic

threshold calculated with the Korean method was approximately 49% lower than

that calculated using the U.S. method. Additionally, the epidemic durations

based on the Korean thresholds were longer than those based on the U.S. and

European thresholds.

Interpretation

The differences in epidemic thresholds between the Korean and the U.S. methods

primarily stemmed from the different definitions of the non-influenza time

period in both countries. In Korea, this period is defined as when the weekly

influenza positivity rate falls below 2%, a figure that is influenced by the

activity levels of other respiratory viruses. In contrast, the U.S. defines the

non-influenza period as the time when the number of weekly influenza-positive

specimens is less than 2% of the season's total count of

influenza-positive specimens, a measure that remains unaffected by the activity

of other respiratory viruses. It is important to note that the 2% influenza

positivity rate used in Korea's definition of the non-influenza period is

significantly lower than the European epidemic threshold of 10%. This

discrepancy results in the use of lower ILI rates from periods of relatively low

influenza activity to calculate the Korean epidemic threshold. Consequently,

this could lead to the earlier issuance and later lifting of influenza epidemic

alerts.

The largest difference between the epidemic durations determined by ILI

rate-oriented thresholds and those determined by influenza positivity

rate-oriented thresholds was observed in the 2022–2023 season. The

epidemic duration based on the Korean method was 49 weeks, which was roughly 3

times longer than the 16-week epidemic duration based on the European threshold.

This discrepancy can be partially attributed to changes in the incidence levels

of overall respiratory infectious diseases. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the

implementation of stringent social distancing measures and enhanced personal

hygiene practices led to a reduced incidence of respiratory infections. However,

this low incidence began to increase as public health measures were relaxed in

the latter half of 2022. Subsequently, a resurgence of various respiratory

infections elevated the overall ILI rates, which likely contributed to the

extended epidemic period by interacting with the lower epidemic threshold in the

2022–2023 season [

12,

13].

According to project reports from the Korea Respiratory Virus Integrated

Surveillance System, which tests respiratory samples from respiratory infection

patients, including cases of ILI, at sentinel sites, the influenza virus

detection rates in 2022 and 2023 were 5.5% and 16.1%, respectively. These rates

are similar to or lower than the rates of 17% and 14% observed in 2018 and 2019,

before the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, the detection rates of SARS-CoV-2 in

2022 and 2023 were 9.4% and 9.8%. The detection rates of other respiratory

viruses have also increased since 2021 (

Table

5) [

11,

14,

15]. This finding

is consistent with a report that the first post-pandemic influenza epidemic was

not considered unexpected in terms of extent and severity in most countries

[

16]. Therefore, the increase in ILI

rates in the 2022–2023 season is likely due to the increased activity of

SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses, rather than a significant increase in

influenza activity.

Table 5.Virological surveillance results of respiratory specimens

|

Year |

Total respiratory virus positivity

[% (n*)] |

Influenza virus positivity

[% (n*)] |

SARS-CoV-2 virus positivity [%

(n*)] |

Other respiratory virus†

positivity [% (n*)] |

|

2023 |

81.4 (Na) |

16.1 (Na) |

9.8 (Na) |

55.5 (Na) |

|

2022 |

72.7 (Na) |

5.5 (491) |

9.4 (Na) |

57.8 (5,205) |

|

2021 |

65.1 (3,009) |

0 (0) |

NA |

65.1 (3,009) |

|

2020 |

48.6 (2,830) |

12 (701) |

NA |

36.6 (2,129) |

|

2019 |

60.2 (7,311) |

14 (1,702) |

NA |

46.2 (5,609) |

|

2018 |

63.0 (Na) |

17 (Na) |

NA |

46.0 (Na) |

ILI is a widely used medical concept and a reliable indicator in influenza

surveillance [

17]. However, since the

clinical features of various respiratory infections often overlap, a rise in

influenza activity alone may not fully explain the increase in ILI rates. When

analyzing a rise in ILI rates, it is crucial to consider all circulating

respiratory pathogens collectively, in conjunction with laboratory test results,

to determine the extent to which each pathogen contributes to the increase

[

18]. The ongoing influenza epidemic

in Korea since the 37th week of 2022 appears to be a phenomenon resulting from

the combination of the lower influenza epidemic threshold in Korea and the

overall increase in ILI rates due to the increased activity of SARS-CoV-2 and

other respiratory viruses.

The study did not explore the characteristics of each epidemic threshold, such as

the sensitivity and specificity of its application. Merely comparing the

durations of epidemic periods does not determine which method should be

recommended for a specific country. The approach to setting the influenza

epidemic threshold should be assessed differently, taking into account each

country’s health system capacity and disease burden. In this study, the

influenza epidemic thresholds used in the U.S. and Europe were only compared

with those in Korea. Additional comparisons with other countries may increase

the generalizability of the study findings.

Conclusion

Influenza surveillance systems are designed to minimize the socioeconomic losses

caused by influenza epidemics, making the application of an appropriate epidemic

threshold crucial. This study noted variations in the duration of the epidemic

period based on the threshold applied. A low influenza epidemic threshold may have

contributed to the prolonged epidemic period, which was declared in the 37th week of

2022 and continued until the end of 2023 in Korea. The optimal epidemic threshold

should be examined from various perspectives, including the evolving epidemiological

characteristics of respiratory infectious diseases since the emergence of

SARS-CoV-2. Adopting multiple indicators could enable the issuance of more reliable

flu alerts and the implementation of more effective countermeasures.

Authors' contributions

-

Project administration: Lee J

Conceptualization: Lee J

Methodology & data curation: Lee J

Funding acquisition: not applicable

Writing – original draft: Lee J

Writing – review & editing: Lee J, Huh S, Seo H

Conflict of interest

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

-

Not applicable.

Data availability

-

The data used in this study are retrieved from the infectious diseases portal of

the KDCA available from: https://dportal.kdca.go.kr/pot/is/st/influ.do

Data files are available from Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9ZYE8N

Dataset 1. Research data used to draw Fig.

1, which shows seasonal influenza activity during the 2018−2019

season in Korea according to different influenza epidemic thresholds in Korea,

the United States, and Europe

Dataset 2. Research data used to draw Fig.

2, which shows seasonal influenza activity during the 2019−2020

season in Korea according to different influenza epidemic thresholds in Korea,

the United States, and Europe

Dataset 3. Research data used to draw Fig.

3, which shows seasonal influenza activity during the 2022−2023

season in Korea according to different influenza epidemic thresholds in Korea,

the United States, and Europe

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Supplementary materials

-

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Biggerstaff M, Cauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L. Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and

zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:480

- 2. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Management strategies for seasonal influenza, 2023-24 season. Cheongju: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; 2023.

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

[CDC]. U.S. influenza surveillance: purpose and methods [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; c2024 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/overview.htm

- 4. Brammer L, Budd A, Cox N. Seasonal and pandemic influenza surveillance considerations for

constructing multicomponent systems. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2009;3(2):51-58.

- 5. Spencer JA, Shutt DP, Moser SK, Clegg H, Wearing HJ, Mukundan H, et al. Distinguishing viruses responsible for influenza-like

illness. J Theor Biol 2022;545:111145

- 6. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

[ECDC]. Seasonal influenza 2022-2023: annual epidemiological report for

2023. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023.

- 7. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Announcement of 2023-2024 influenza season initiation

[Internet]. Cheongju (KR): Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; c2023 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501010000&bid=0015&list_no=723470&cg_code=&act=view&nPage=1

- 8. Tamerius JD, Shaman J, Alonso WJ, Bloom-Feshbach K, Uejio CK, Comrie A, et al. Environmental predictors of seasonal influenza epidemics across

temperate and tropical climates. PLOS Pathog 2013;9(3):e1003194.

- 9. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. 2022 Annual report on infectious disease reports [Internet]. Cheongju (KR): Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; c2022 [cited 2024 Feb 16]. Available from https://dportal.kdca.go.kr/pot/bbs/BD_selectBbs.do?q_bbsSn=1010&q_bbsDocNo=20230908669355443&q_clsfNo=1

- 10. Lee JW. Another flu season declaration… The first season continued for

more than a year [Internet]. Seoul (KR): The Dong-a Ilbo; c2023 [cited 2023 Sep 15]. Available from https://www.donga.com/news/Health/article/all/20230915/121190131/1

- 11. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Infectious diseases, sentinel surveillance report [Internet]. Cheongju (KR): Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; c2024 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. Available from https://dportal.kdca.go.kr/pot/bbs/BD_selectBbsList.do?q_bbsSn=1010&q_bbsDocNo=&q_clsfNo=2&q_searchKeyTy=&q_searchVal=&q_currPage=1&q_sortName=&q_sortOrder=

- 12. Cha J, Seo Y, Kang S, Kim I, Gwack J. Sentinel surveillance results for influenza and acute respiratory

infections during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Public Health Wkly Rep 2023;16(20):597-612.

- 13. Kim IH, Kang SK, Cha JO, Seo YJ, Gwack J, Lee NJ, et al. Changes in patterns of respiratory virus since the coronavirus

disease 2019 pandemic (until April 2023). Public Health Wkly Rep 2023;16(20):621-631.

- 14. Lee NJ, Woo S, Lee J, Rhee JE, Kim EJ. 2021-2022 Influenza and respiratory viruses laboratory

surveillance report in the Republic of Korea. Public Health Wkly Rep 2023;16(3):53-65.

- 15. Woo SH, Lee NJ, Lee JH, Rhee JE, Kim EJ. Korea 2022-2023 influenza and respiratory viruses laboratory

surveillance report. Public Health Wkly Rep 2024;17(2):455-469.

- 16. de Jong SPJ, Felix Garza ZC, Gibson JC, van Leeuwen S, de Vries RP, Boons GJ, et al. Determinants of epidemic size and the impacts of lulls in

seasonal influenza virus circulation. Nat Commun 2024;15(1):591

- 17. Fleming DM, Elliot AJ. Lessons from 40 years' surveillance of influenza in

England and Wales. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136(7):866-875.

- 18. Kelly H, Birch C. The causes and diagnosis of influenza-like

illness. Aust Fam Physician 2004;33(5):305-309.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Pertussis epidemic in Korea and implications for epidemic control

Joowon Lee

Infectious Diseases.2025; 57(2): 207. CrossRef - Invasive Group A Streptococcus infections in children during the post-pandemic period: results from a multicenter study in Italy

Elena Chiappini, Marco Renni, Maia De Luca, Samantha Bosis, Silvia Garazzino, Laura Dotta, Raffaele Badolato, Federica Zallocco, Daniele Zama, Antonella Frassanitto, Ilaria Liguoro, Danilo Buonsenso, Claudia Colomba, Lorenza Romani, Giulia Lorenzetti, Fed

Italian Journal of Pediatrics.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - The paradox of rapid and synchronized propagation of seasonal influenza ‘A’ outbreaks in contrast with COVID-19: a testable hypothesis

Uri Gabbay, Doron Carmi

Virus Research.2025; 362: 199670. CrossRef - Gender equity in medicine, artificial intelligence, and other

articles in this issue

Sun Huh

The Ewha Medical Journal.2024;[Epub] CrossRef