Abstract

-

Objectives:

This study analyzed drug-induced death statistics in Korea between 2011 and

2021.

-

Methods:

Cause-of-death statistics data from Statistics Korea were examined based on

the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases and Causes of Death and the

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health

Problems, 10th revision.

-

Results:

In 2021, there were 559 drug-induced deaths, marking a 172.7% increase

compared to 2011, which recorded 205 deaths. The rate of drug-induced deaths

per 100,000 people was 1.1 in 2021, up 153.6% from 0.4 in 2011. The

mortality rate for men aged 25−34 years and women aged 35−44

years each increased fourfold from 2011 to 2021: from 0.3 to 1.2 for the

former and 0.3 to 1.3 for the latter. Of the drug-induced deaths in 2021,

75.0% (419/559) were due to intentional self-harm, and 10.4% (58/559) were

accidental. The number of deaths attributed to medical narcotics in 2021 was

169, a 5.5-fold increase from 2011. The most commonly implicated drugs in

these deaths were sedative-hypnotic drugs, benzodiazepines, and opioids.

Sedative-hypnotic drugs and benzodiazepines were frequently involved in

cases of intentional self-harm, while opioids and psychostimulants were more

often associated with accidental deaths.

-

Conclusion:

The death rate from drug-induced causes is considerably lower in Korea than

in the United States (1.1 vs. 29.2). However, the number of such deaths has

increased recently. Since these deaths occur predominantly among younger age

groups and are often the result of intentional self-harm, there is a clear

need for systematic management and the implementation of targeted

policies.

-

Keywords: Cause of death; Narcotics; Analgesics; opioid; International Classification of Diseases; Republic of Korea

Introduction

Background

Deaths caused by drugs are both preventable and avoidable. Furthermore, drug

overdose represents a significant issue that requires policy intervention, as it

can escalate into larger social problems. Recently, drug abuse has emerged as a

major global concern. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, there were 106,699 drug overdose deaths in 2021, marking a sharp

increase since 2000. Notably, there has been a significant rise in deaths

attributed to opioids such as fentanyl [

1,

2]. The impact of drugs on

mortality involves both direct and indirect factors. Direct causes refer to

cases where the primary cause of death is drug-related, as classified by the

World Health Organization (WHO) in the International Standard Classification of

Diseases (ICD-10). Indirect factors involve drug use increasing the risk of

deaths from other causes, such as intentional self-harm, liver disease,

hepatitis, and heart disease. The Global Burden of Disease study reported that

drug use is responsible for approximately 114,000 indirect deaths and 350,000

direct deaths annually [

3].

This study analyzed the characteristics of drug-related deaths, aiming to inform

and support drug-related policies. Additionally, it sought to identify risk

factors associated with drug-related deaths to aid in the development of

strategies to reduce such fatalities. The report specifically focused on the

demographic characteristics, types of deaths, and the various drugs involved in

drug-induced fatalities.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study involved an analysis of public data; therefore, neither approval by

the institutional review board nor the obtainment of informed consent was

required.

Study design

This descriptive study was based on public data from Statistics Korea, and it was

described according to the STROBE Statement available from:

https://www.strobe-statement.org/.

This study analyzed microdata on cause of death statistics from Statistics Korea

spanning from 2011 to 2021 to examine the characteristics of drug-related

deaths. The cause of death statistics in Korea are compiled from death

certificates. To enhance the accuracy of determining the underlying cause of

death, Statistics Korea integrates 22 types of administrative data for each

individual. The detailed administrative data includes health insurance

information from the National Health Insurance Service, cancer registry data

from the National Cancer Center, criminal investigation records and traffic

accident investigation data from the National Police Agency, autopsy records

from the National Forensic Service, emergency records from the National

Emergency Medical Center, among others. Notably, drug-related deaths are

reliably documented, reflecting data from police investigations and autopsy

reports provided by the National Forensic Service. The ICD-10 code list for

causes of death due to drugs is provided in Supplement 1. Deaths due to drugs

were categorized by cause of death into disease, accident, intentional

self-harm, and homicide, and further analyzed by classifying the drugs involved

into opioids, sedatives, and psychotropic agents.

Bias

There was no bias in data collection and analysis.

Study size

The entire population of the Republic of Korea was included. No sample size

estimation was required.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were applied to present the results of the data

analysis.

Results

Drug-induced death

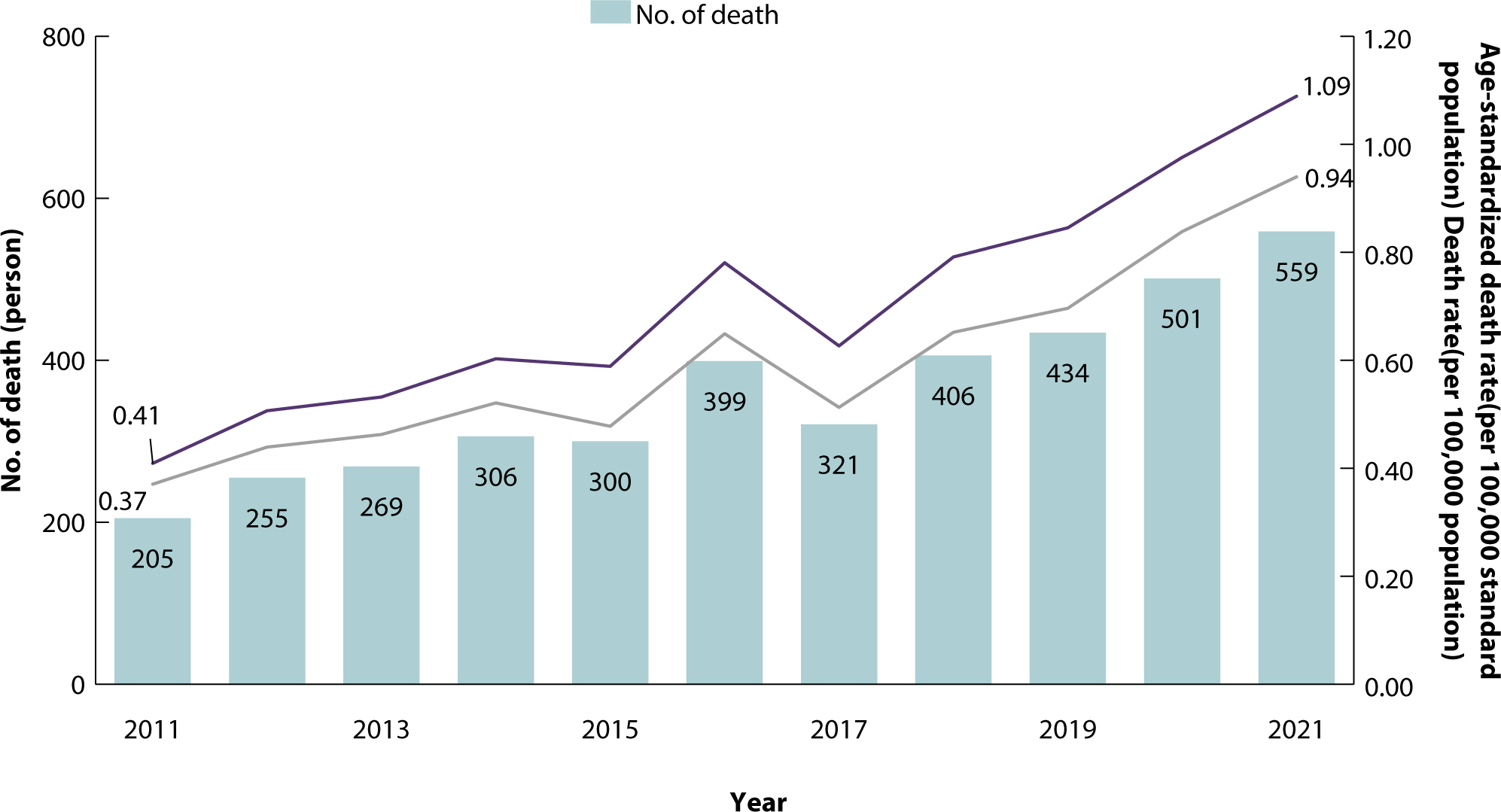

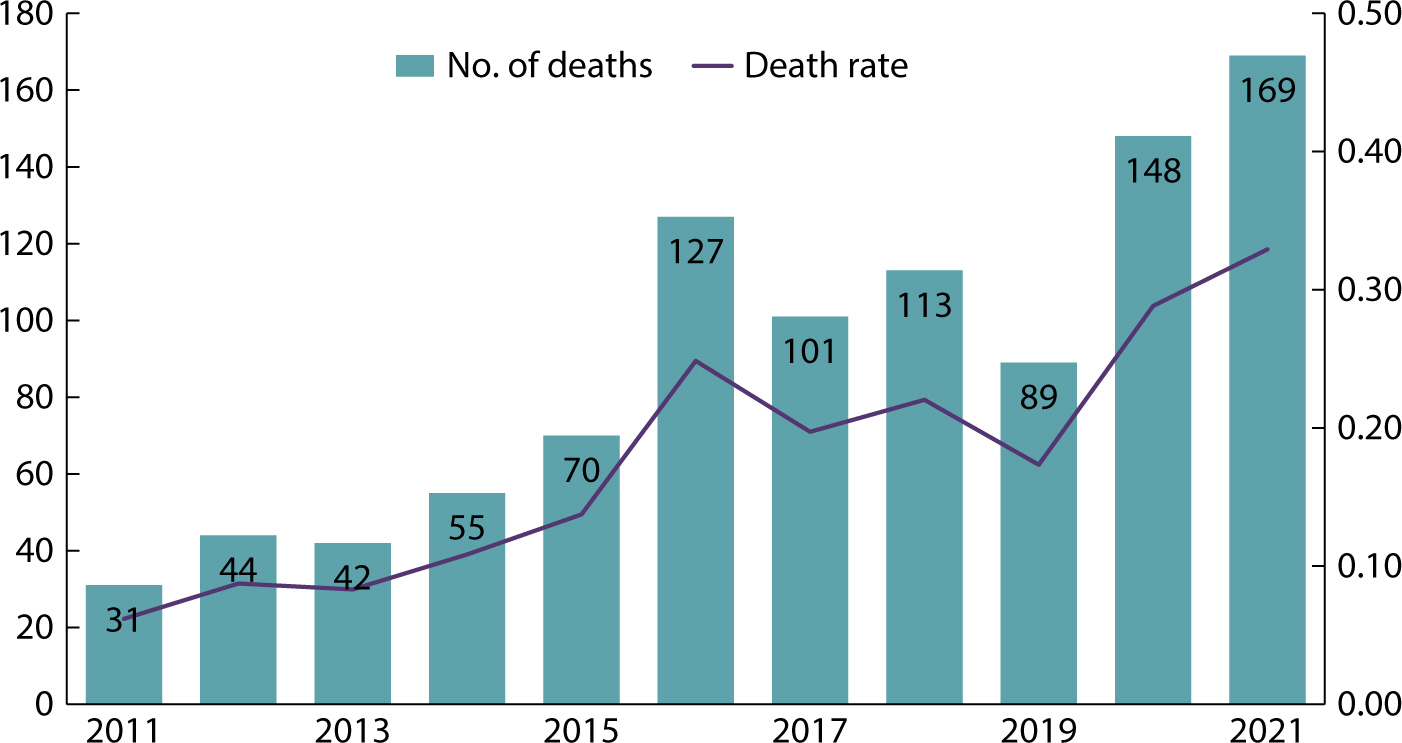

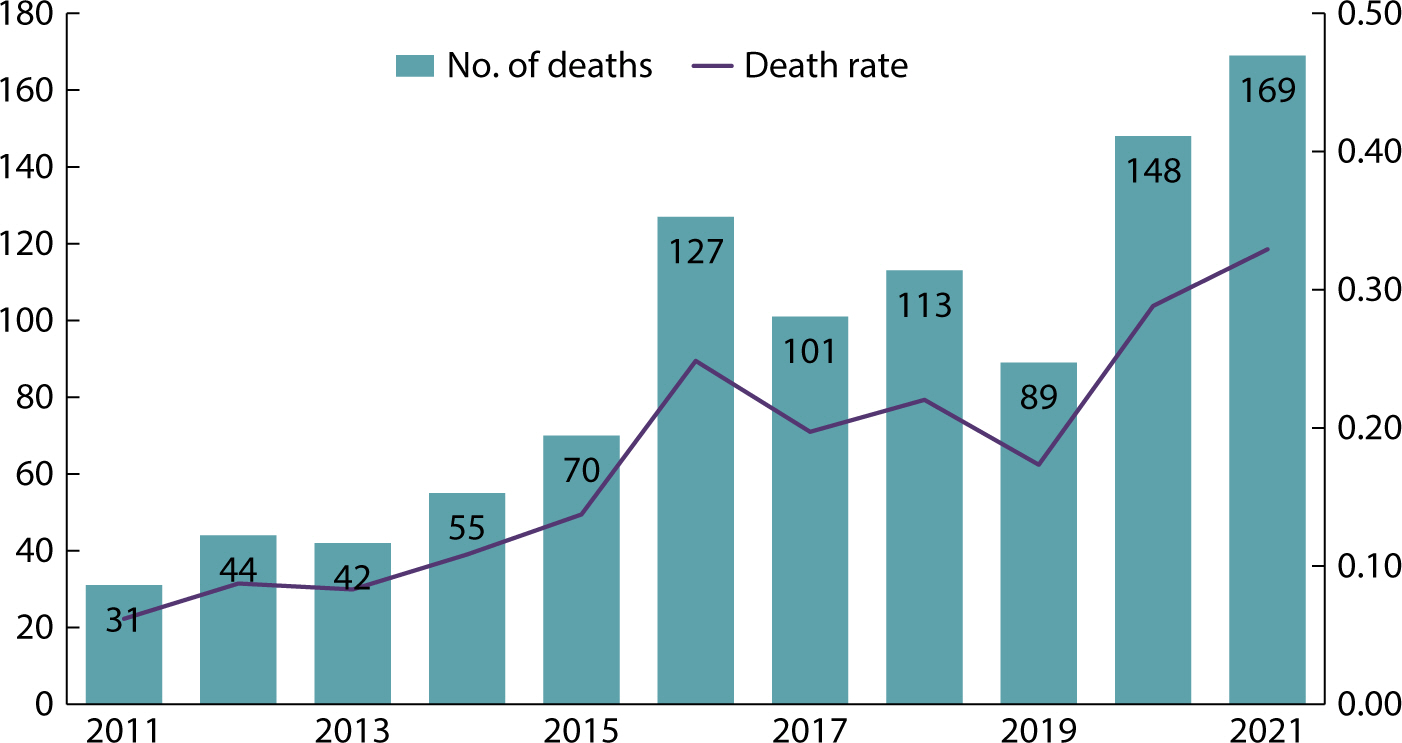

In 2021, there were 559 drug-induced deaths in Korea, marking a 172.7% increase

from the 205 deaths recorded in 2011 (

Table

1,

Fig. 1). The average number

of drug-induced deaths per day was 1.5. The mortality rate was 1.1 per 100,000

population, and the age-standardized mortality rate was 1.1 per 100,000

standardized population. Deaths due to drugs steadily increased throughout the

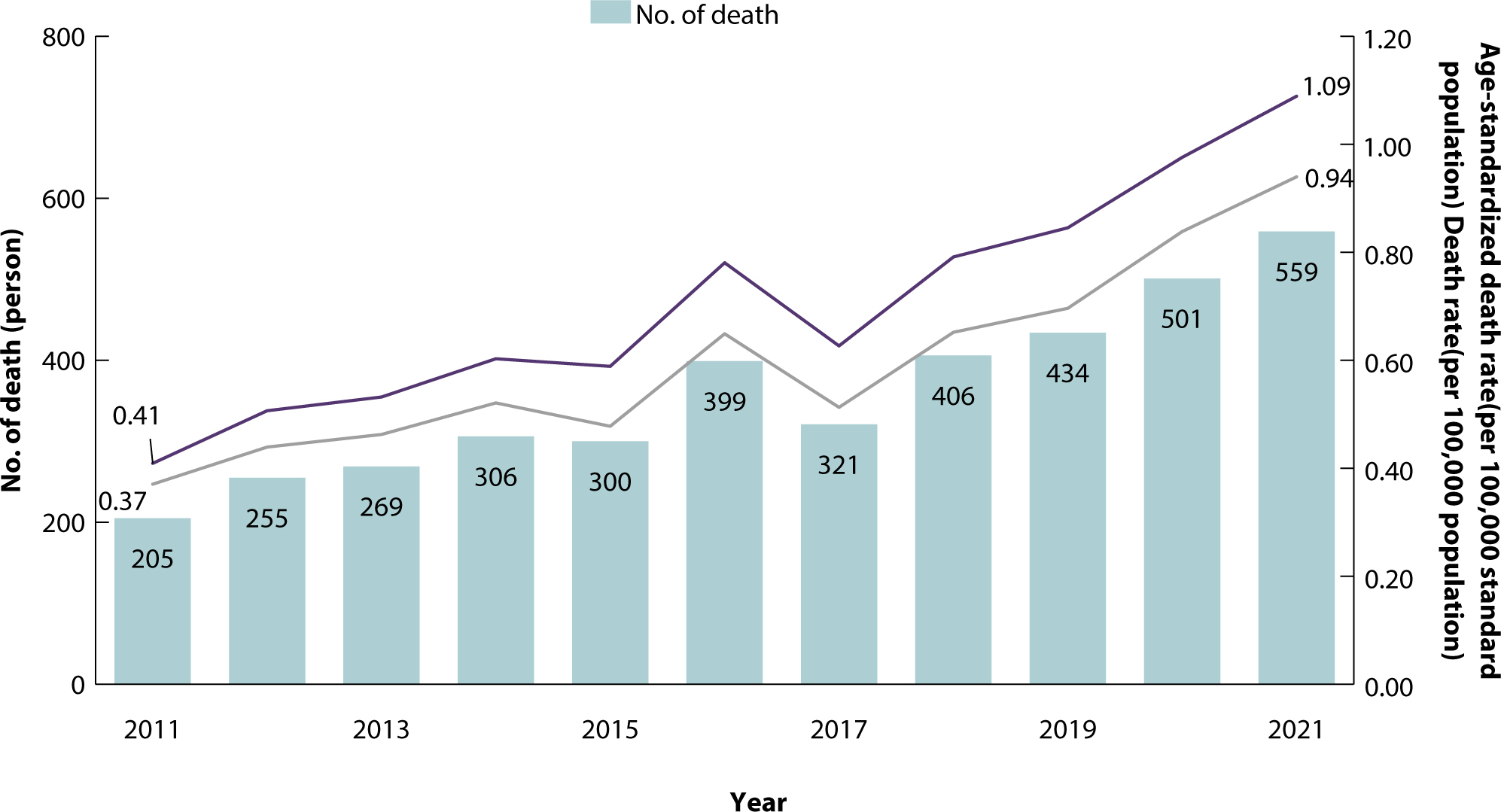

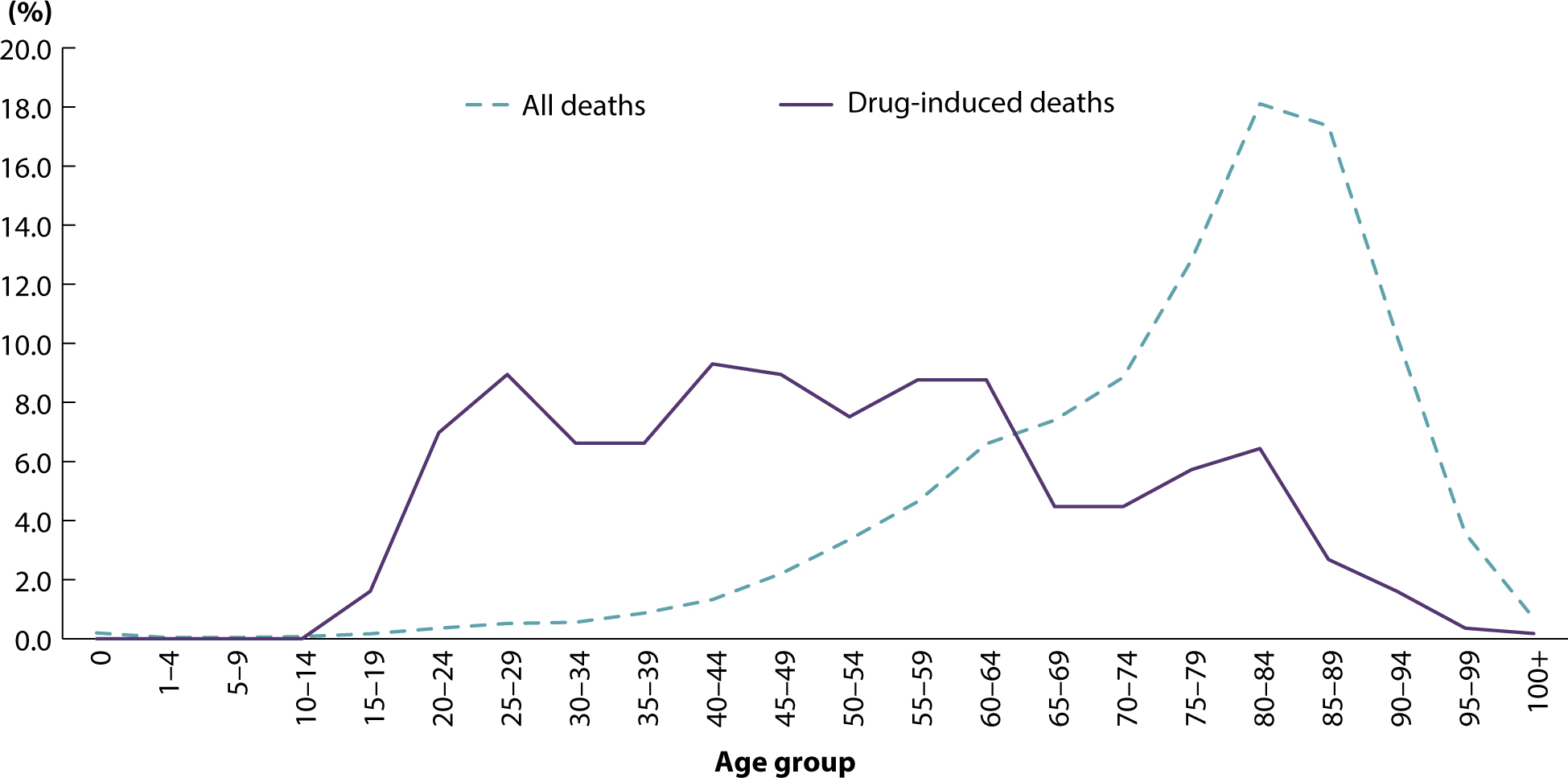

study period and predominantly occurred in relatively young age groups (

Fig. 2). While the highest percentage of all

deaths in 2021 occurred in individuals aged 80−84 (18.1%), a significant

proportion of drug-related deaths occurred in those aged 64 or younger.

Table 1.The number of drug-induced deaths, death rate, and age-standardized

death rate between 2011 and 2021

|

Year |

No. of deaths (deaths) |

Death rate

(deaths per

100,000 population) |

Age-standardized death

rate

(deaths per 100,000 standard population) |

|

2011 |

205 |

0.41 |

0.37 |

|

2012 |

255 |

0.51 |

0.44 |

|

2013 |

269 |

0.53 |

0.46 |

|

2014 |

306 |

0.60 |

0.52 |

|

2015 |

300 |

0.59 |

0.48 |

|

2016 |

399 |

0.78 |

0.65 |

|

2017 |

321 |

0.63 |

0.51 |

|

2018 |

406 |

0.79 |

0.65 |

|

2019 |

434 |

0.85 |

0.7 |

|

2020 |

501 |

0.98 |

0.84 |

|

2021 |

559 |

1.09 |

0.94 |

|

Change (absolute) |

|

|

|

|

from 2011 |

354 |

0.7 |

0.57 |

|

from 2020 |

58 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Change (proportional, %) |

|

|

|

|

from 2011 |

172.7 |

166.2 |

153.6 |

|

from 2020 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

10.8 |

Fig. 1.Drug-induced deaths, death rate, and age-standardized death rate,

2011−2021 (units: people, per 100,000 people, and per 100,000

standard population).

Fig. 2.Proportional age distribution for drug-induced deaths versus total

deaths, 2021.

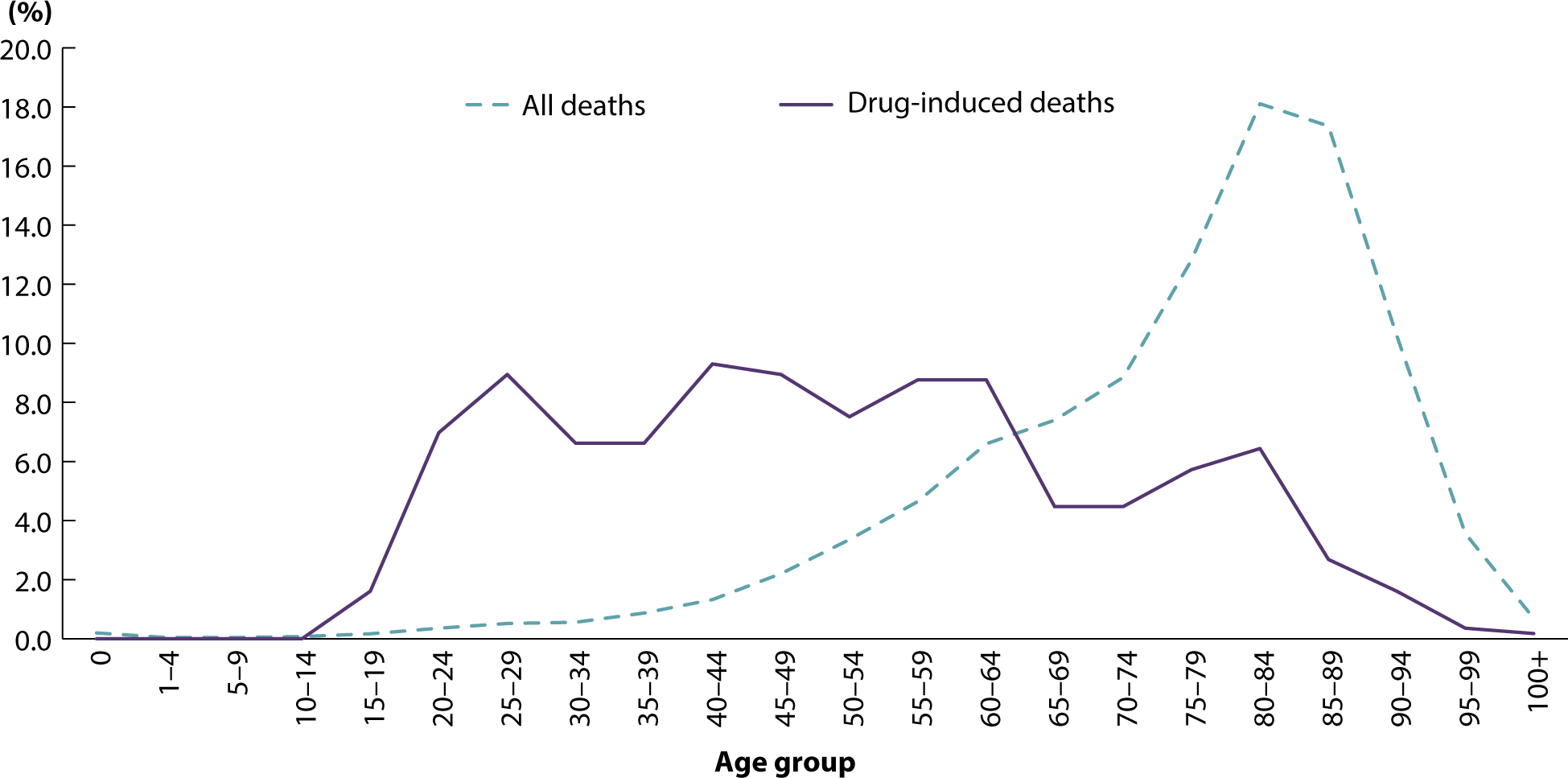

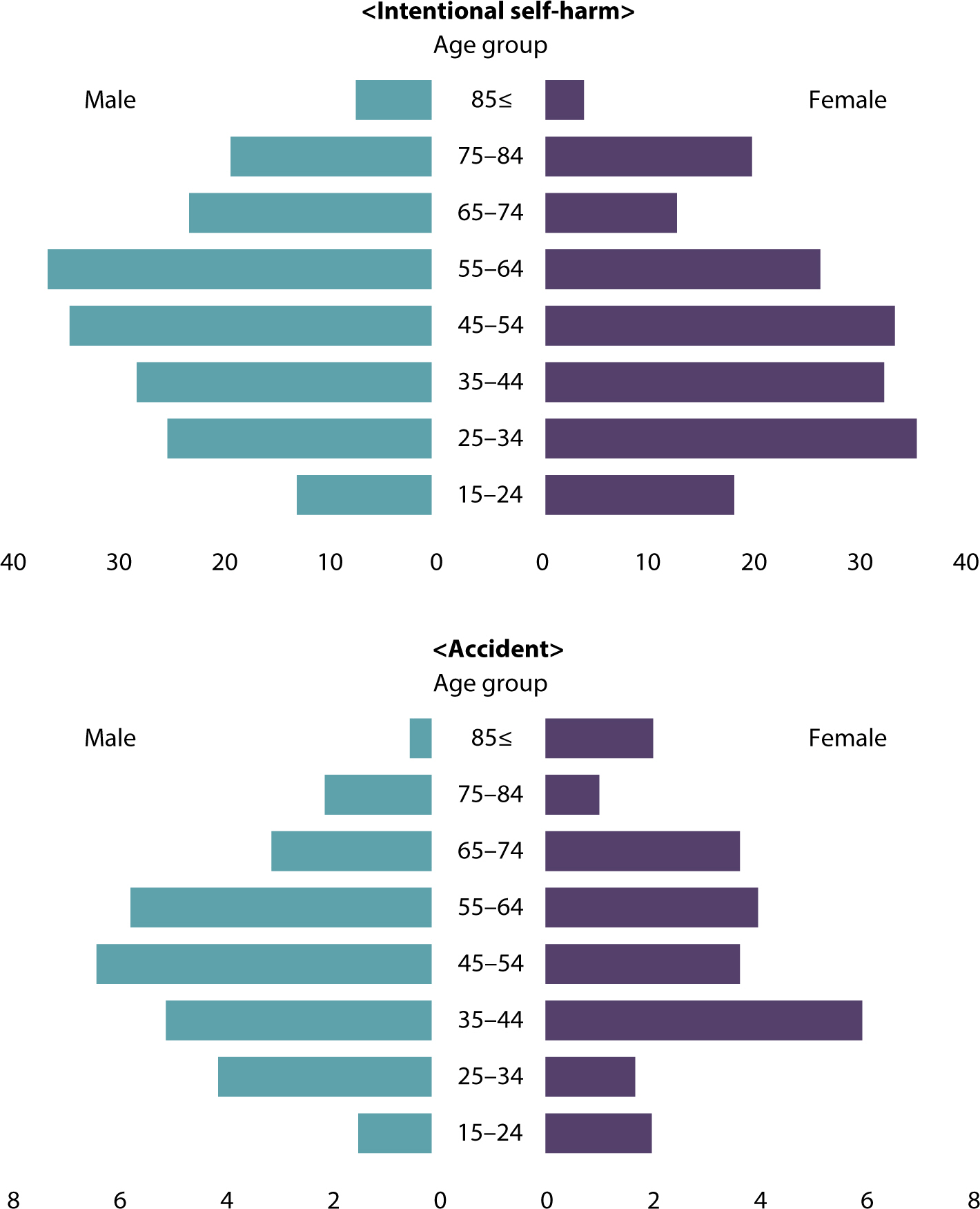

Compared to 2011, the number of deaths in 2021 increased across all age groups

for both men and women, with a notable rise in the younger demographics.

Specifically, the mortality rate for men aged 25 to 34 and for women aged 15 to

24 saw significant increases (Supplement 2). Of the deaths caused by drugs in

2021, 75.0% were intentional self-harm and 10.4% were unintended accidents. The

number of deaths attributed to intentional self-harm involving drugs has

increased since 2011. Over the past three years, the average age at death from

drug-related causes has been consistently lower for women than for men (

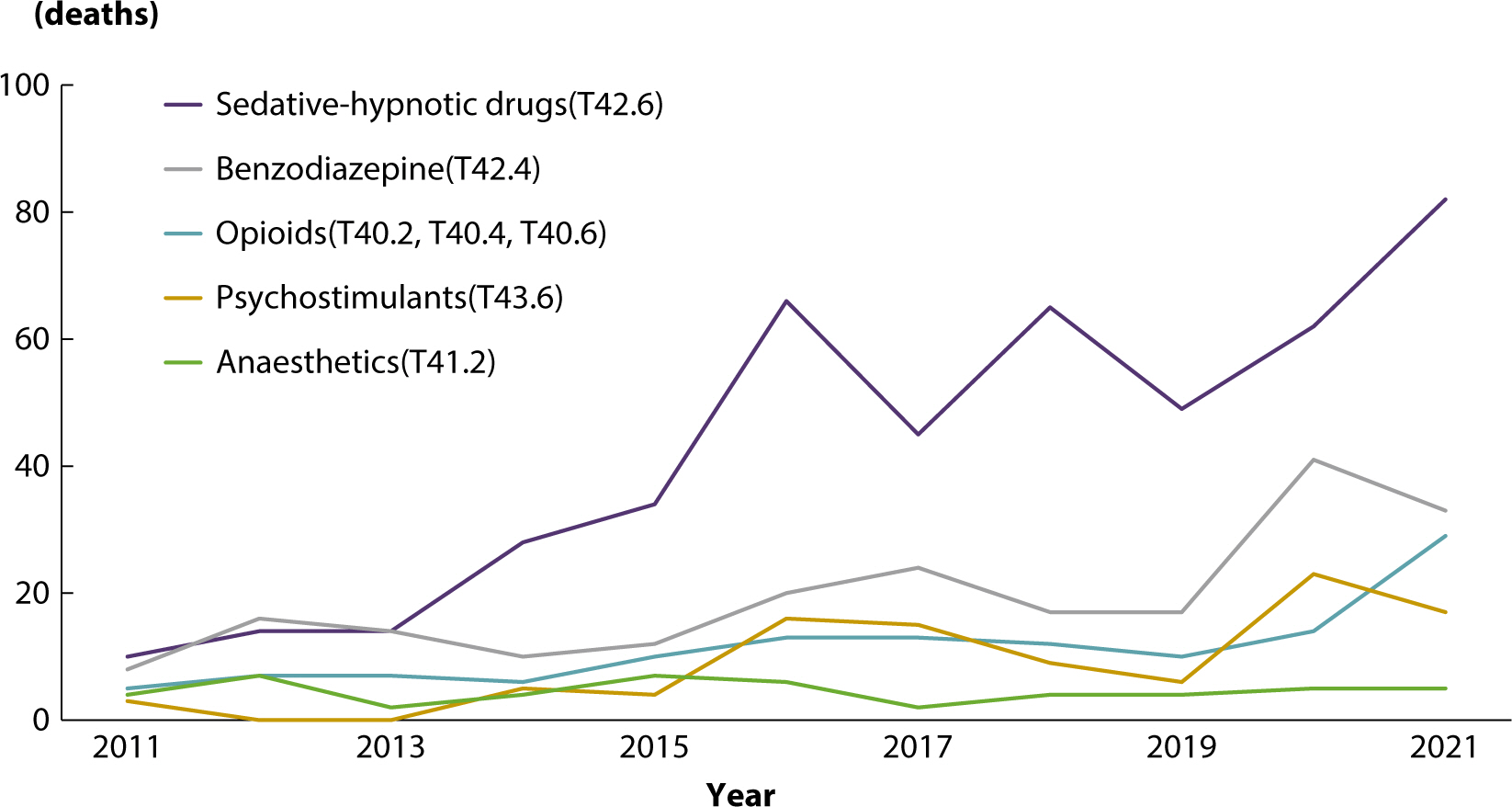

Fig. 3). When categorizing deaths by drug

type since 2011, the three most prevalent drugs based on their effects were

sedatives and sleeping pills, such as zolpidem and benzodiazepines; psychotropic

drugs, including antidepressants and neuroleptics; and a combination of

narcotics and psychotropic drugs, notably fentanyl (Supplement 3).

Fig. 3.Annual average number of drug-induced deaths by sex and age,

2019−2021.

Death due to medical narcotics

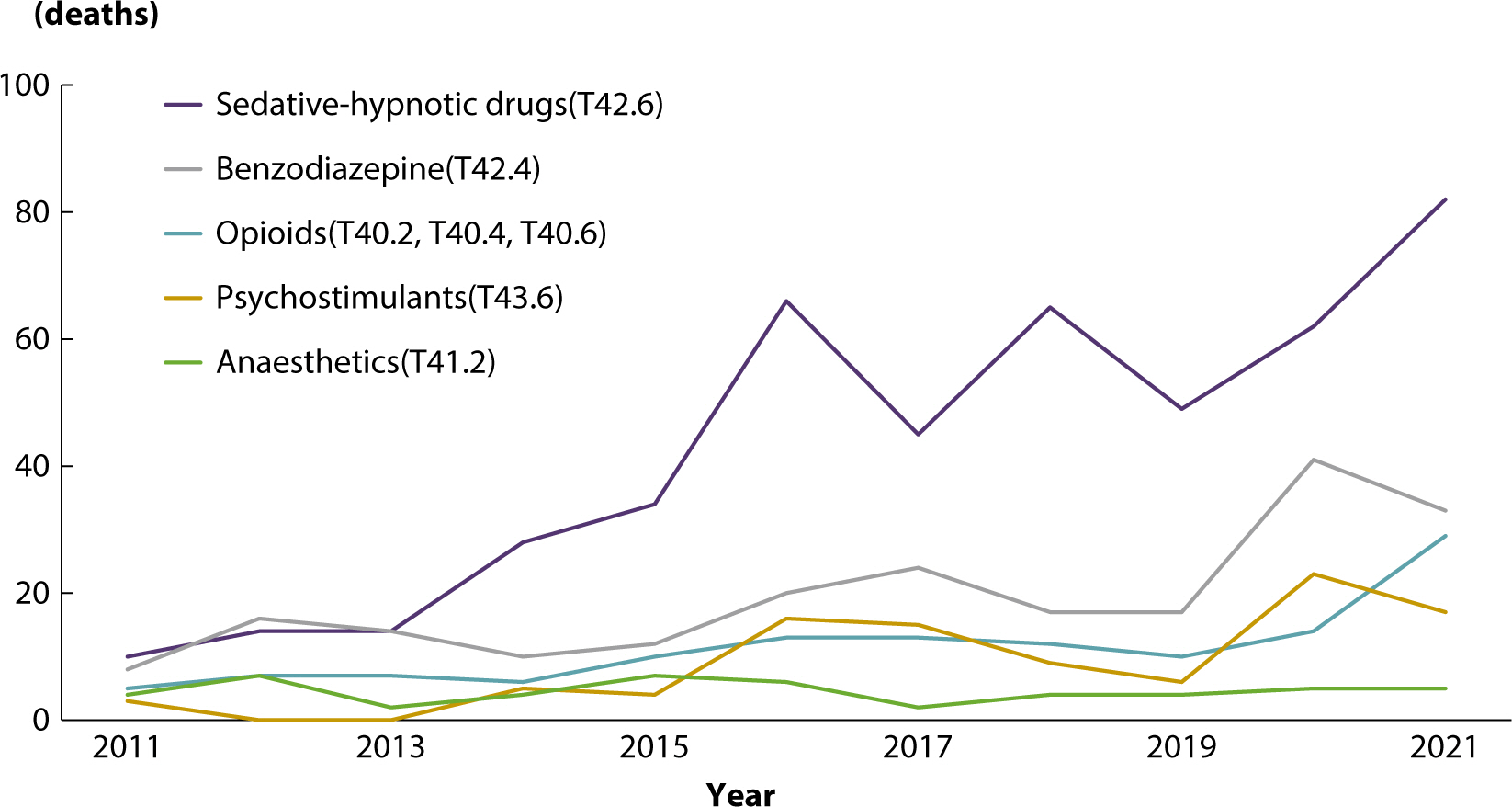

To analyze deaths specifically attributed to designated medical narcotics in

Korea, narcotic drugs were categorized according to ICD-10 codes (Supplement 1).

In 2021, there were 169 deaths due to medical narcotics, representing a 5.5-fold

increase from the 31 deaths recorded in 2011. Although the number of deaths

decreased from 127 in 2016 to 89 in 2019, there has been a rapid increase for

two consecutive years (

Fig. 4). A detailed

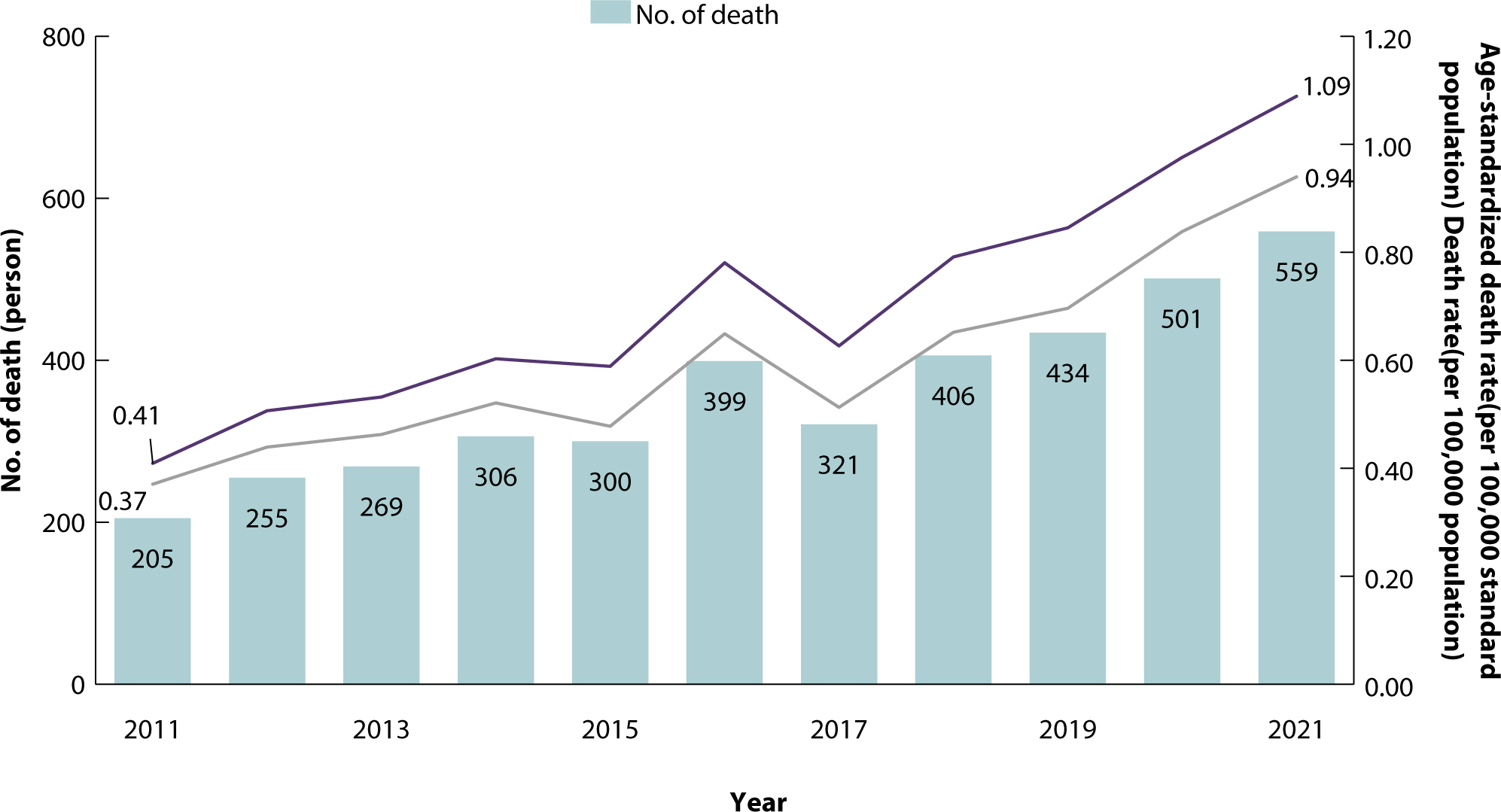

breakdown of deaths by type of medical narcotic shows that sedative-hypnotic

drugs account for the highest number, followed by benzodiazepines and opioids.

Notably, the number of deaths associated with sedative-hypnotic drugs, such as

zolpidem, and opioids, such as fentanyl, is on the rise (

Fig. 5). Men had a higher proportion of deaths involving

psychostimulants than women, and women had a higher proportion of deaths

involving sedative-hypnotic drugs, general anesthetics, and appetite depressants

than men. An analysis of medical narcotics deaths by age between 2019 and 2021

revealed that the risk of death from narcotics varied with age. Specifically,

opioids accounted for a high proportion of deaths among individuals aged 25 to

54, benzodiazepines were involved in a large proportion of deaths among those

aged 45 to 64, sedative-hypnotic drugs predominated among those aged 55 to 74,

and deaths related to general anesthetics were most common among those aged 25

to 34 (

Table 2).

Fig. 4.Number of deaths and death rate due to medical narcotics,

2011−2021.

Fig. 5.Number of deaths due to medical narcotics, 2011−2021.

Table 2.The number of deaths due to medical narcotics by age group between

2019 and 2021 (unit: deaths)

|

Age group |

Opioids (T40.2, T40.4, T40.6) |

Anesthetics (T41.2) |

Benzodiazepine (T42.4) |

Sedative-hypnotic drugs (T42.6) |

Others (T41.1, T42.3, T43.6, T48.3,

T50.5) |

|

15−24 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

3 |

8 |

|

25−34 |

12 |

6 |

7 |

16 |

7 |

|

35−44 |

14 |

4 |

8 |

19 |

15 |

|

45−54 |

11 |

2 |

17 |

31 |

16 |

|

55−64 |

8 |

0 |

22 |

42 |

6 |

|

65−74 |

4 |

0 |

13 |

42 |

3 |

|

75−84 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

29 |

- |

|

≥85 |

3 |

0 |

5 |

11 |

- |

Among deaths attributed to medical narcotics, psychostimulants and opioids

represented a significant percentage of accidental fatalities. In instances of

intentional self-harm, sedative-hypnotic drugs and benzodiazepines were commonly

employed. Specifically, sedative-hypnotic drugs constituted 56.7% of

drug-related intentional self-harm cases (Supplement 4).

To analyze the risk of death associated with the use of medical narcotics, the

number of health insurance claims for narcotics was compared to the number of

deaths. For both opioids and psychotropic drugs, the proportion of deaths

relative to the number of claims is higher in younger age groups, indicating

that the risk of death from narcotic drugs is comparatively high among the

young. Specifically, the number of deaths relative to the number of opioid

claims in the 25−44 age group represents a higher proportion compared to

other age groups (Supplement 5).

Discussion

Key results

In 2021, there were 559 drug-induced deaths, marking a 172.7% increase from the

205 deaths recorded in 2011. The rate of drug-induced deaths per 100,000 people

rose to 1.1 in 2021, up 153.6% from 0.4 in 2011. Of the drug-induced deaths in

2021, 75.0% were due to intentional self-harm, and 10.4% were accidental. Deaths

attributed to medical narcotics reached 169 in 2021, a significant increase, up

5.5 times from 31 in 2011. The most commonly involved drugs in these fatalities

were sedative-hypnotic drugs, benzodiazepines, and opioids.

Interpretation

While most deaths occur between the ages of 80 and 84, the majority of

drug-related deaths took place in individuals under the age of 64 (

Fig. 2). This suggests that deaths due to

drugs often result in premature mortality compared to other causes, thereby

disproportionately increasing the disease burden. Furthermore, there has been a

significant rise in the risk of death among younger age groups over the past

decade. Given that 75% of drug-related deaths are due to intentional self-harm

(

Fig. 3), it is evident that

intentional self-harm involving drugs has significantly contributed to the

increased mortality rates in this demographic. This trend highlights the

emergence of drug-induced intentional self-harm as a pressing social issue.

Deaths due to medical narcotics have increased more rapidly than those due to

other drugs (

Fig. 4). Gender differences

were observed in deaths from medical narcotics: men were more likely to die from

drugs with stimulating effects, while women were more likely to die from drugs

with sedative effects. The types of medical narcotics associated with the

highest mortality rates also varied by age, reflecting the fact that the most

commonly prescribed drugs and treatments differ across age groups (Supplement

5). Notably, benzodiazepines were disproportionately involved in deaths among

the young age group of 15 to 24 years old (

Table

2). Because opioids are often used as painkillers for terminal cancer

patients, there are limited medical applications of opioids in younger age

groups. However, there are two potential reasons for the relatively high risk of

opioid-related deaths among young people. The first is the misuse of narcotic

drugs, where death results from intentional misuse without adhering to

prescribed dosages or methods of administration. The second involves medication

being obtained through illegal distribution or purchase, rather than being

prescribed through a legitimate health insurance system. To conduct a thorough

analysis, it is essential to prepare big data linking narcotic drug

prescriptions to death data.

Among medical narcotics, drugs with sedative effects—including

sedative-hypnotic drugs, anesthetics, and benzodiazepines—are frequently

used for intentional self-harm (Dataset 1). Therefore, these drugs require

special management. When comparing the number of health insurance claims to the

number of deaths associated with medical narcotics, the ratio for individuals

aged 25−44 was notably high (

Table

2). This indicates an elevated risk of death in this younger age

group, necessitating targeted management and policies to reduce drug-related

deaths.

No previous articles have reported drug-induced death statistics in Korea. As

drug addiction becomes an increasingly significant social issue in many

countries, including the United States, the need for robust statistics to inform

related policies is becoming more apparent. In the United States, the

age-standardized drug-induced death rate for the total population increased by

29.4% from 22.8 in 2019 to 29.5 in 2020 [

2]. The European Union has developed an estimation model to address the

problem of undercounting drug-related deaths [

4].

Lack of statistical indicators related to drug-induced deaths

The need for policy support to address drug-related deaths is growing, yet

there is a significant shortage of statistical indicators that can determine

the extent and risk factors associated with these fatalities. This scarcity

of statistical indicators for drug-induced deaths stems from three primary

factors.

The first issue is the incompleteness of the criteria used to classify deaths

caused by drugs. Typically, the management of drug distribution and

prescriptions is governed by the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

Classification (ATC) codes, which are designated by the Collaborating Center

for Pharmaceutical Statistics Methods (WHOCC), an affiliate of the WHO. Each

ATC code is structured into five levels: drug application site, drug

efficacy, drug characteristics, chemical properties, and individual

ingredients. This detailed classification system facilitates the specific

categorization of drugs, such as opioid-related drugs and benzodiazepines.

However, when classifying causes of death, the ICD-10 from the International

Standard Classification System (WHO-FIC), another affiliate of the WHO, is

utilized. The data on the number of deaths derived from ICD-10 codes is not

without its limitations. Due to inconsistencies in code ranges, deaths

caused by drugs other than narcotics are inadvertently included. For

instance, the T48.3 code, which denotes poisoning by cough medicine,

encompasses drugs other than the medical narcotics dextromethorphan and

zipeprol. Nonetheless, the risk of death and addiction is significantly

higher with medical narcotics than with other general drugs. Additionally,

the T43.6 code, which refers to intoxication by psychostimulants with abuse

potential, primarily includes methylphenidate, a legal drug used to treat

attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, and methamphetamine, an

illegal substance. The ICD-10 coding system’s limitations in terms of

the details of drug classification suggest that there is potential for

further subdivision in the upcoming revised ICD-11. Thus, the classification

systems for drug prescriptions and causes of death differ significantly,

particularly in that the cause-of-death codes do not adequately classify

drugs in detail.

The second factor is the scarcity of data regarding drug-induced deaths.

While drug prescriptions are well-documented, including details about the

recipient, the dosage, and the specific medications prescribed, information

about drug-related deaths can typically only be obtained through an autopsy

or toxicology testing. Furthermore, elderly individuals often take various

medications for multiple conditions, and it is not uncommon for younger

people to intentionally consume multiple drugs.

Third, there is a lack of linked data spanning prescriptions, illnesses, and

deaths. It is crucial to determine whether drug-related deaths are due to

acute or chronic poisoning. Furthermore, the underlying diseases and health

status of the deceased should be taken into account to accurately assess the

impact of the drug on mortality. Therefore, analyzing data that connects

prescriptions, illnesses, and deaths is essential. By examining linked data,

it would be possible to empirically ascertain the risk of death associated

with a drug by comparing its risk and efficacy against the number of people

prescribed the drug or the dosage prescribed.

Because cause-of-death statistics must adhere to the standards set by the

WHO, analyses involving multiple drugs or drug efficacy, which are necessary

for drug death statistics, are not suitable. Therefore, new, separate

statistics are required to accurately identify the characteristics of deaths

caused by drugs.

How to improve drug-related death statistics

The target population for these statistics is defined as Korean citizens

whose deaths are associated with drugs. Determining whether drugs are

related to a death is only possible through autopsy results; therefore, the

actual population is defined as those cases where drugs were detected in

autopsies conducted by the National Forensic Service. To develop new

statistics using autopsy data, it is essential to establish standards for

classifying drugs. In the statistics for drug-induced deaths among Koreans,

the statistical classification (ATC code) used for drug prescription and

management does not align with the code that classifies the cause of death

(ICD-10). Currently, the ICD-10 does not specify detailed drug types.

Therefore, a linkage table between the ICD-11 and ATC codes must be

developed. To ensure the stability of time series in this linkage table,

ICD-10 codes can be additionally linked to construct statistics using a

consistent classification system from the drug prescription stage through to

the death stage. By developing statistics that classify autopsy data using

both ATC codes and ICD-11 codes, it becomes possible to analyze not only the

efficacy and type of drugs but also the risks associated with polypharmacy.

With detailed classification of drug types, it would be feasible to

construct linked big data that spans drug prescription, disease prevalence,

and death.

Data sources for linked big data necessitate the integration of health

insurance claim details, autopsy data, and cause-of-death statistics. These

linked datasets can serve as empirical evidence for analyzing drug death

risks and drug safety. Specifically, when multiple drugs are consumed, it is

possible to analyze further that the risk of death may increase due to

synergistic effects.

Among many countries, the method Australia uses to compile cause-of-death

statistics is similar to that of Korea, making drug-induced death statistics

from Australia highly relevant to Korea. Generally, drug-related deaths are

prone to underestimation; however, the reliability of these statistics is

enhanced in Australia by incorporating the coroner’s approval

process, and in Korea by including both autopsy results and police

investigations in the statistical compilation [

5,

6]. Australia

has compiled statistics on drugs and opioids and has implemented targeted

policies, which have led to a decrease in mortality rates.

Conclusion

As drug prices fall and online transactions on platforms like the dark web and

cryptocurrency become more prevalent, making them difficult to trace, the risk of

drug-related deaths has increased. This is compounded by a rise in the overseas

inflow of drugs. Therefore, statistical indicators that can be used to establish and

evaluate related policies are essential. It is anticipated that this study and

further in-depth analysis will facilitate the development of future research that

will identify population groups at risk for drug use, provide targeted educational

support, and establish guidelines, ultimately helping to reduce the risk of

premature death due to drugs.

Authors' contributions

-

All work was done by Seokmin Lee.

Conflict of interest

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

-

Not applicable.

Data availability

-

Raw data are available from microdata on cause of death statistics from

Statistics Korea from 2011 to 2021 at https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/index.do

Data files are available from Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/D3CXBJ

Dataset 1. Drug-induced deaths, including deaths due to medical narcotics, from

2011 to 2021 by sex, age, type of death, marital status, and educational

attainment provided by Statistics Korea

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Supplementary materials

-

Supplementary materials are available from: https://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2024.e27.

Supplement 1. ICD-10 codes for causes of death due to drugs

Supplement 2. The number of deaths and death rate due to drugs by sex and age

Supplement 3. The ranking of deaths due to drug characteristics between 2011 and

2021

Supplement 4. Number of deaths due to medical narcotics by type of death between

2019 and 2021

Supplement 5. Number of deaths compared to the number of medical narcotic

prescriptions by age between 2019 and 2021

Supplement 6. Data used to generate Figs. 1–5

References

- 1. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2023;72(10):1-92.

- 2. Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States,

2001—2021. NCHS Data Brief 2022;(457):1-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:122556

- 3. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

[OECD]. Addressing problematic opioid use in OECD countries [Internet]. Paris (FR): OECD; c2019 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from https://doi.org/10.1787/a18286f0-en

- 4. Giraudon I, Mathis F, Hedrich D, Vicente J, Noor A. Drug-related deaths and mortality in Europe: update from the EMCDDA

expert network [Internet]. Lisbon (PT): European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug

Addiction; c2021 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from https://doi.org/10.2810/777564

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of death [Internet]. Canberra (AT): Australian Bureau of Statistics; c2021 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. Available from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Opioid-induced deaths in Australia [Internet]. Canberra (AT): Australian Bureau of Statistics; c2019 [cited 2023 Oct 4] Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/opioid-induced-deaths-australia