Abstract

-

Objectives: Addiction to prescription narcotics is a global issue,

and detecting individuals with narcotic use disorder (NUD) at an early stage can

help prevent narcotics misuse and abuse. We developed a novel index for the

early detection of NUD based on an analysis of real-world prescription patterns

in a large hospital.

Methods: We analyzed the narcotic prescriptions of 221,887 patients,

prescribed by 8,737 doctors from July 2000 to June 2018. To facilitate the early

detection of patients at risk of developing NUD after a prolonged period of

narcotic use, we developed a weighted morphine equivalent daily dose (wt-MEDD)

score. This score was based on the number of prescription dates where the actual

MEDD exceeded the intended MEDD. We compared the performance of the wt-MEDD

scoring system in identifying patients diagnosed with NUD by doctors against

other high-risk NUD indices. These indices included the MEDD scoring system, the

number of days on prescribed narcotics, the frequency and duration of

prescriptions, narcotics prescriptions from multiple doctors, and the number of

early narcotic refills.

Results: A wt-MEDD score cut-off value of 10.5 successfully

identified all outliers and diagnosed patients with NUD with 100% sensitivity

and 99.6% specificity. This score demonstrated the highest sensitivity and

specificity for detecting NUD compared to all other indexes. The predictive

performance was further improved by combining the wt-MEDD score with other

high-risk NUD indexes.

Conclusion: We developed a novel index, the wt-MEDD score, which

showed excellent performance in the early detection of NUD.

-

Keywords: Narcotic use disorder; Drug abuse detection method; Overlapping MEDD; MEDD ratio

Introduction

Background/rationale

According to the 2020 World Drug Report [

1], the number of deaths due to opioid overdose has increased by 2.5

times, rising from 18,515 in 2007 to approximately 47,000 in 2018. A significant

aspect of the current overdose crisis is the growing addiction to prescription

narcotics [

2]. Among patients prescribed

narcotics for chronic pain, 21%–29% misuse them, and 8%–12%

develop an addiction to these drugs [

3].

In recent years, there has been a growing public awareness of the severity of

addiction to prescription narcotics [

4].

Narcotic abuse can be defined in various ways; for example, MedlinePlus defines

prescription narcotic abuse as "taking medicine in a way that is

different from what the doctor prescribed" [

5]. The primary cause of narcotics abuse is often a strong

desire to obtain more narcotics than those prescribed by doctors, driven by a

"strong desire or urge to use the substance" [

6]. To combat prescription narcotic use

disorder (NUD), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the

United States has issued guidelines for prescribing narcotics [

7]. Most states now mandate the registration

of narcotic users through prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which

track narcotic prescriptions [

8].

According to the CDC guidelines, prescribing a morphine milligram equivalent

(MME) per day of ≥90 as the morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) should

be minimized as much as possible [

7]. Some

studies have indicated that this system has decreased the prevalence of NUD and

its sequelae [

9,

10], but a recent review has reported ambiguous results

[

11].

A limitation of the CDC guideline and PDMP is that they can only detect the risk

of NUD, not NUD itself. Furthermore, the cut-off values for the NUD high-risk

indexes are not definitive standards for identifying patients at risk of NUD.

For instance, the MEDD restriction cut-off varies significantly between

countries: it is 90 MME/day in the USA and 200 MME/day in Canada [

12]. Although numerous studies have sought

to develop tools to predict NUD, these tools primarily focus on analyzing

high-risk factors rather than detecting NUD itself [

13,

14]. Therefore,

there is a need to develop a method that can definitively identify abnormal

prescription patterns indicative of NUD.

Hence, in this study, we developed a method to screen for patients with NUD by

directly applying the definition of prescription narcotic abuse to analyze

extensive real-world clinical data. Patients employing multiple strategies to

obtain additional narcotics may have an actual MEDD that exceeds the

doctor's intended MEDD due to overlapping prescriptions. To address this,

we introduced a weighted (wt)-MEDD score. This score is calculated based on the

number of prescription dates where the MEDD ratio ([actual MEDD]/[intended

MEDD]) was above a certain level (for example, 1.5), suggesting the presence of

NUD, as per the criteria for prescription narcotics abuse.

Objectives

We assessed the effectiveness of the wt-MEDD score in identifying patients

diagnosed with NUD by physicians at an early stage of the narcotic prescription

pathway, by comparing its performance to that of other narcotic

prescription-related indices.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul

National University Hospital (IRB No. 1806-182-955) and adhered to the ethical

standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for

informed consent was waived because the study was based on database

analysis.

Study design

This retrospective cohort study employed real-world data to develop detection

methods based on a defined criterion for narcotic abuse. The study adhered to

the guidelines outlined in the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational

studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, which can be accessed at:

https://www.strobe-statement.org/.

This study evaluated the total narcotics prescriptions from July 2000 to June

2018 at a single large hospital. Prescriptions for patients with cancer and for

inpatients were excluded from the analysis. The analysis focused on the

following 12 narcotics: fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, morphine,

oxycodone, oxycodone/naloxone, tapentadol, alfentanil, meperidine, remifentanil,

buprenorphine, and nalbuphine. Low-dose narcotics such as codeine and tramadol

were excluded from the study.

Most patterns of NUD involve taking higher doses than those intended by doctors.

The hypothesis was that a patient at risk of developing NUD would employ

multiple strategies to achieve a higher MEDD, resulting in a discrepancy between

the MEDD intended by the doctors and the overlapping MEDD that the patient

achieves through these strategies. Consequently, the MEDD ratio is defined as

follows (

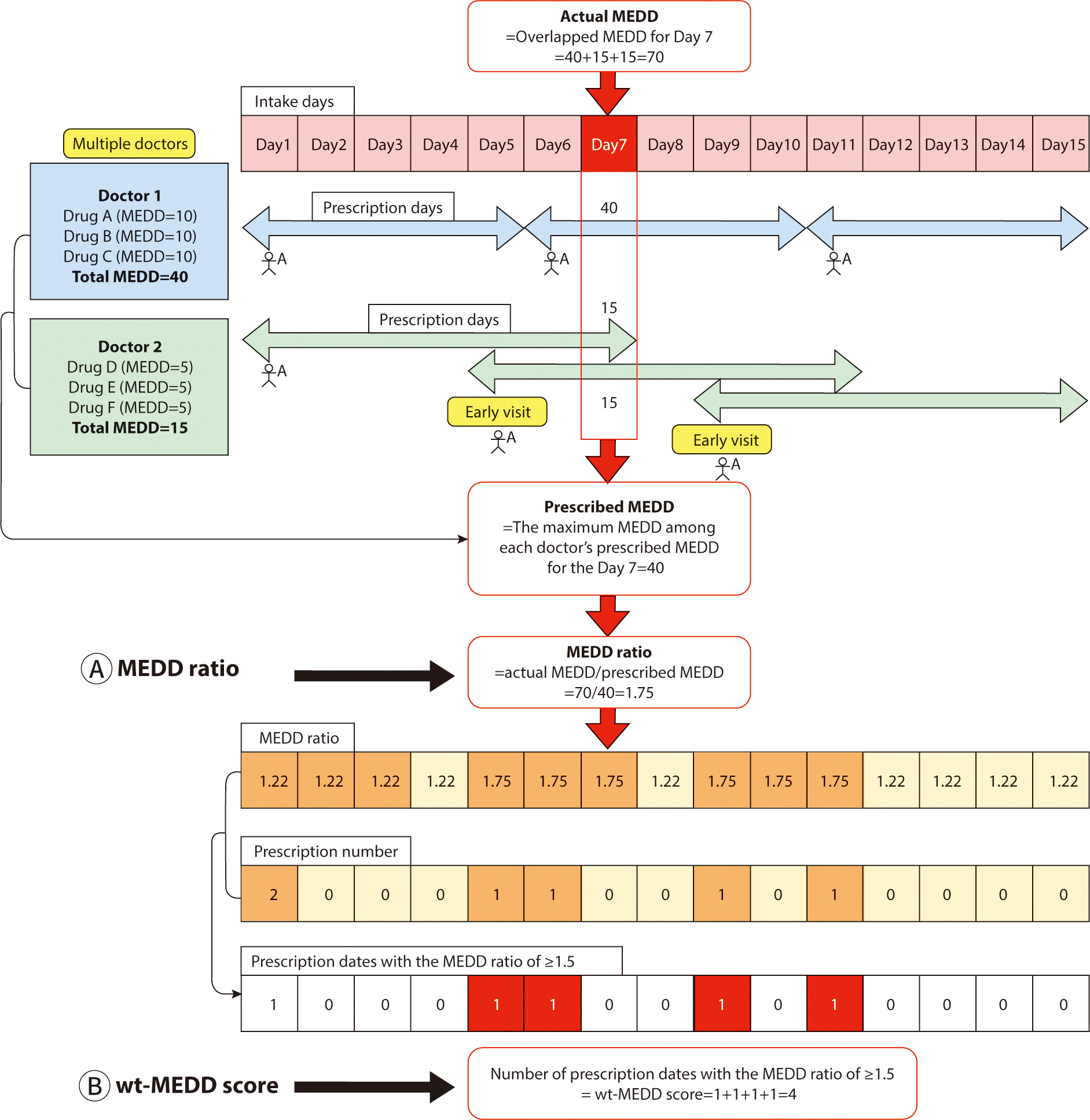

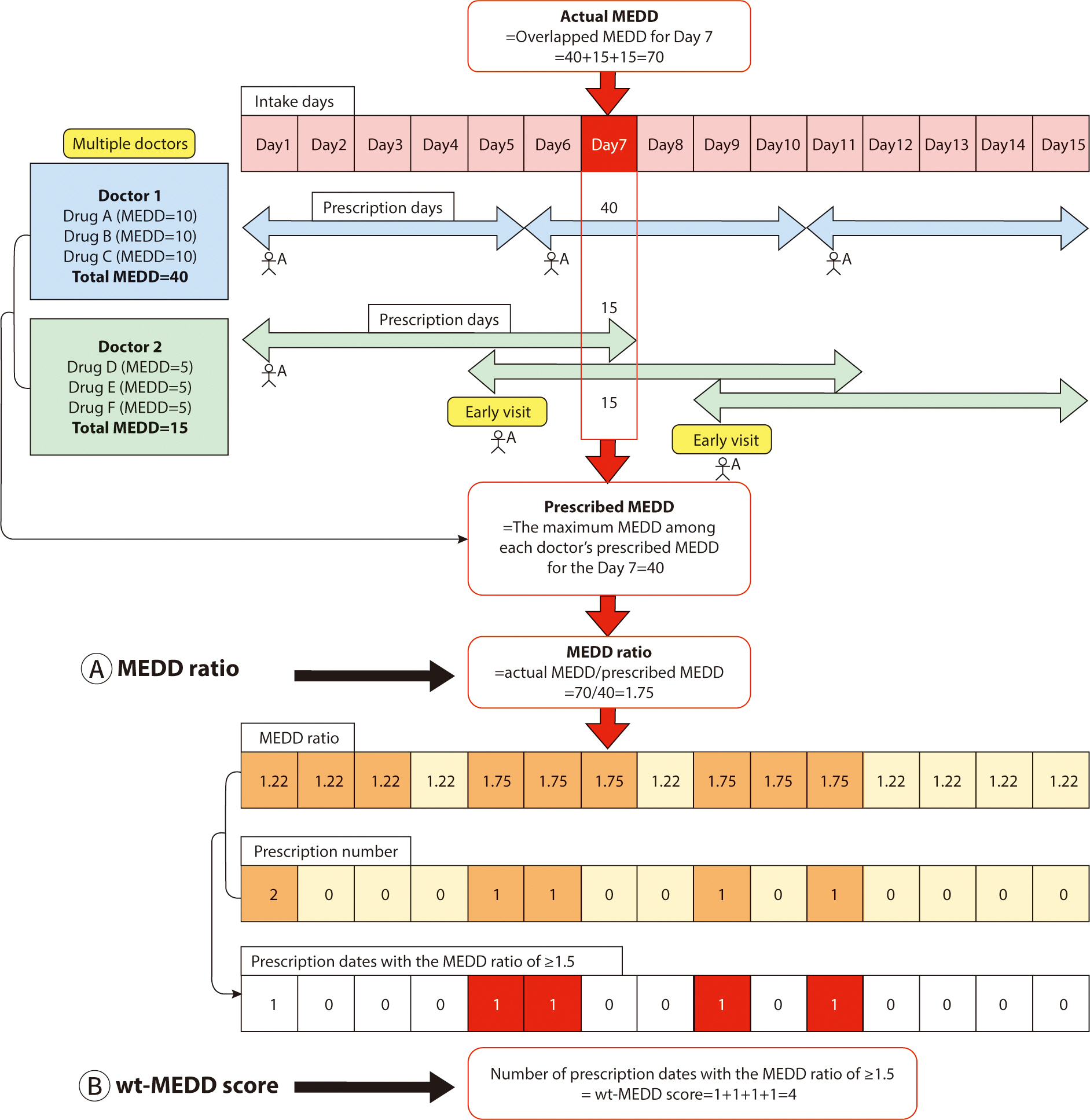

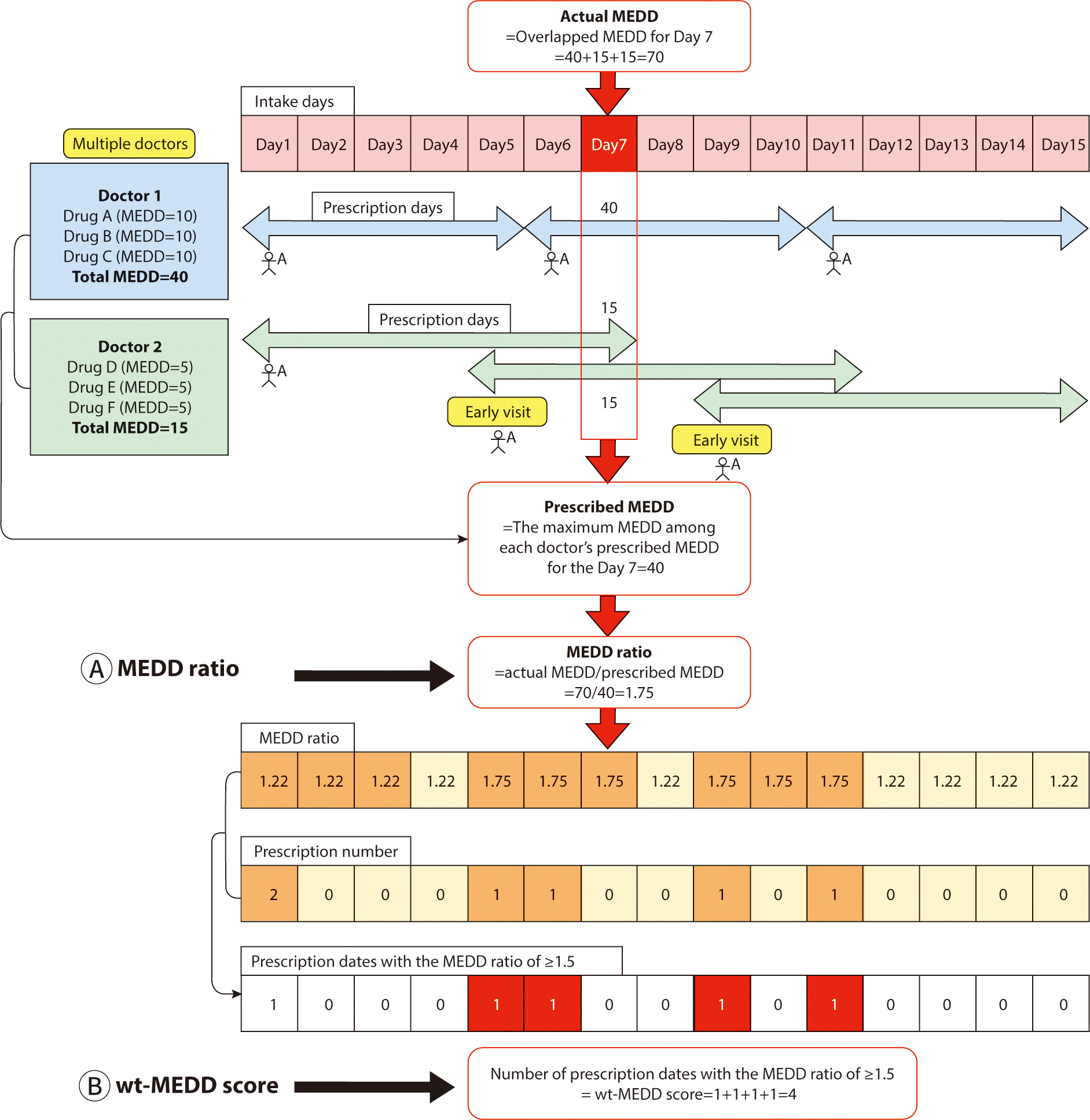

Fig. 1A):

Fig. 1.Schematic diagram of the calculation of the weighted MEDD score.

MEDD, morphine equivalent daily dose; wt-MEDD, weighted MEDD.

For example, doctor 1 prescribes 40 MEDD to patient A, deeming it an appropriate

dosage. However, patient A subsequently visits Doctor 2 to obtain an additional

prescription for narcotics. Unaware of the previous prescription from Doctor 1,

Doctor 2 prescribes an additional 15 MEDD, considering it suitable for patient

A. Later, patient A returns to doctor 2 before the scheduled follow-up, claiming

to have lost the previous prescription, and receives another 15 MEDD.

Consequently, patient A ends up receiving a total of 70 MEDD of narcotics, which

is 1.75 times the highest intended dose of 40 MEDD prescribed by the doctors.

The MEDD ratio, defined as the ratio between the actual MEDD received and the

maximum intended MEDD prescribed by the doctors, is thus 1.75 in this scenario

(

Fig. 1A).

We defined the wt-MEDD score as follows (

Fig.

1B):

In

Fig. 1, patient A consults doctor 1 on

days 1, 6, and 11, and sees doctor 2 on days 1, 5, and 9. This results in a

total of five prescription dates for patient A (days 1, 5, 6, 9, and 11). Out of

these, the number of dates where the MEDD ratio is ≥1.5 amounts to four

(day 5, 6, 9, and 11). The wt-MEDD score, which is defined as the number of

prescription dates with a MEDD ratio of ≥1.5, is therefore 4, as shown in

Fig. 1B. If patient A persists in

obtaining narcotics prescriptions from multiple doctors and visiting them

earlier than scheduled, the wt-MEDD score will continue increasing.

The choice of a MEDD ratio of 1.5—higher than 1.0 but lower than

2.0—was made to accommodate minor discrepancies between the intended MEDD

prescription by doctors and the actual MEDD, such as during initial dose

adjustments at the start of narcotic prescriptions. This range also effectively

identifies abnormal prescriptions that require further review. Ratios below 1.5

may be overly sensitive, failing to distinguish significant deviations between

the actual and intended MEDD. Institutions can adjust the cut-off MEDD ratio

based on their preferences, opting for less than 1.5 to increase sensitivity or

more than 1.5 to increased specificity. The wt-MEDD score served as a proxy for

NUD because repeated prescriptions with a high MEDD rate suggest that the

patient is consistently receiving more narcotics than originally prescribed by

the physician.

We investigated the clinical applicability of the wt-MEDD score, specifically to

monitor abnormal narcotics prescription patterns in a hospital setting. It is

necessary to identify both the doctors and patients involved in these practices

and to provide them with feedback. To this end, we utilized the wt-MEDD score to

compile lists of doctors and patients associated with abnormal prescription

patterns. We identified doctors with outlier wt-MEDD scores and similarly

generated a list of patients exhibiting outlier scores to closely monitor their

prescription behaviors. These individuals were characterized by a two-tailed

P-value of <0.001, corresponding to a Z score of ≥3.29 or

≤–3.29. We then extracted the lists of doctors and patients with

these outlier wt-MEDD scores and determined the cut-off score for both groups to

effectively monitor and address abnormal narcotics prescribing patterns.

Second, we examined whether the wt-MEDD score could be utilized to identify

patients with NUD at an earlier stage. Our analysis focused on determining the

optimal cut-off value of the wt-MEDD score for detecting patients diagnosed with

NUD by physicians, aiming for the highest sensitivity and specificity. If the

cut-off value demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, and if it was

reached before the doctors' diagnosis of NUD, it could serve as an early

indicator for NUD detection. A list of patients diagnosed with NUD by doctors

was extracted from the clinical data warehouse using the codes from the 10th

revision of the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related

Health Problems (ICD-10) and diagnostic terms in the doctors’ medical

chart. The accuracy of the NUD diagnoses was verified by ensuring that the chart

records met the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-IV-TR or DSM-V. We

selected only those patients who had been repeatedly prescribed narcotics at our

hospital prior to their NUD diagnosis. Patients diagnosed with NUD at other

hospitals, who had little or no history of narcotics prescriptions at our

facility, were excluded. Two physicians reviewed the electronic medical record

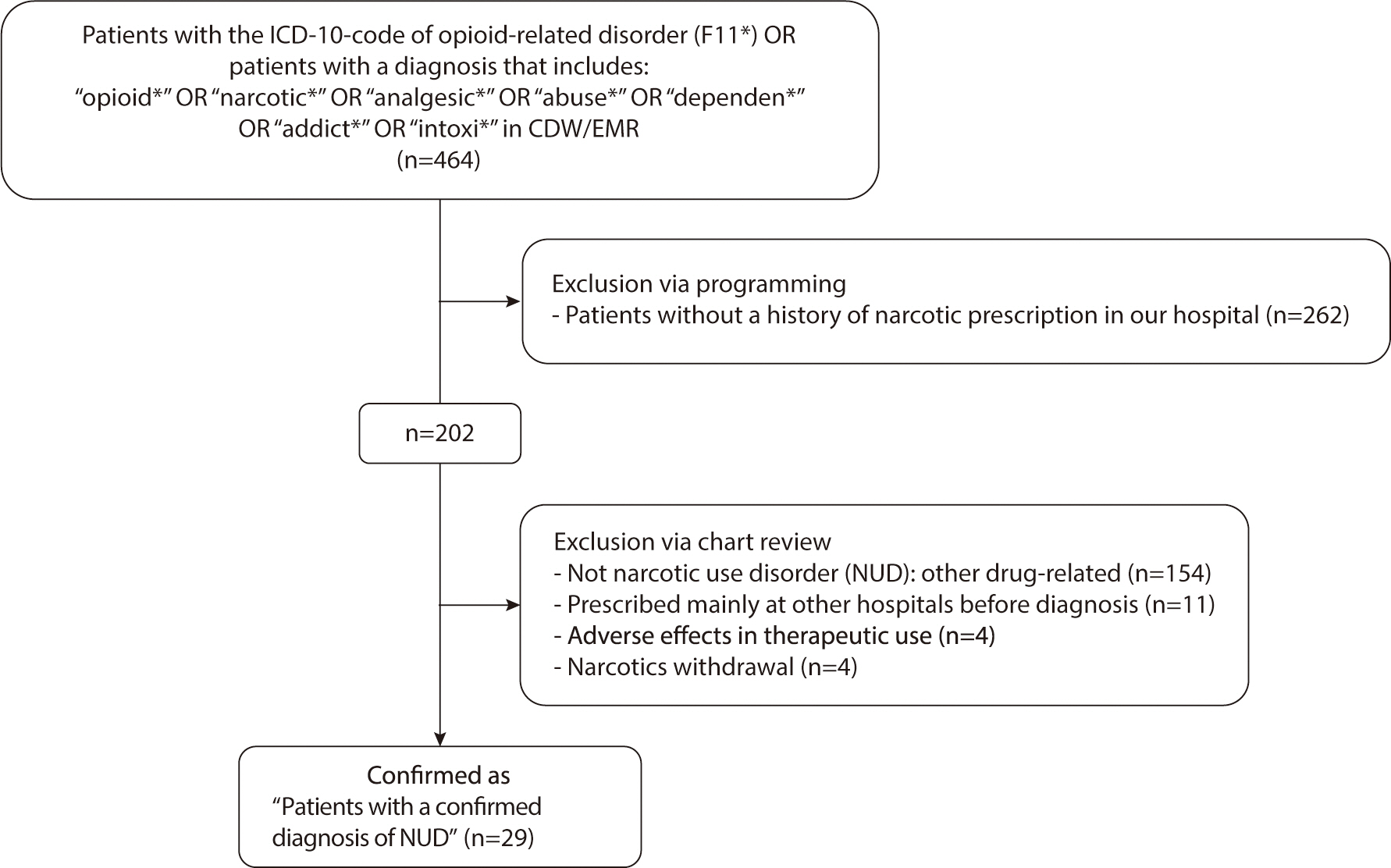

charts to confirm the accuracy of the diagnoses (

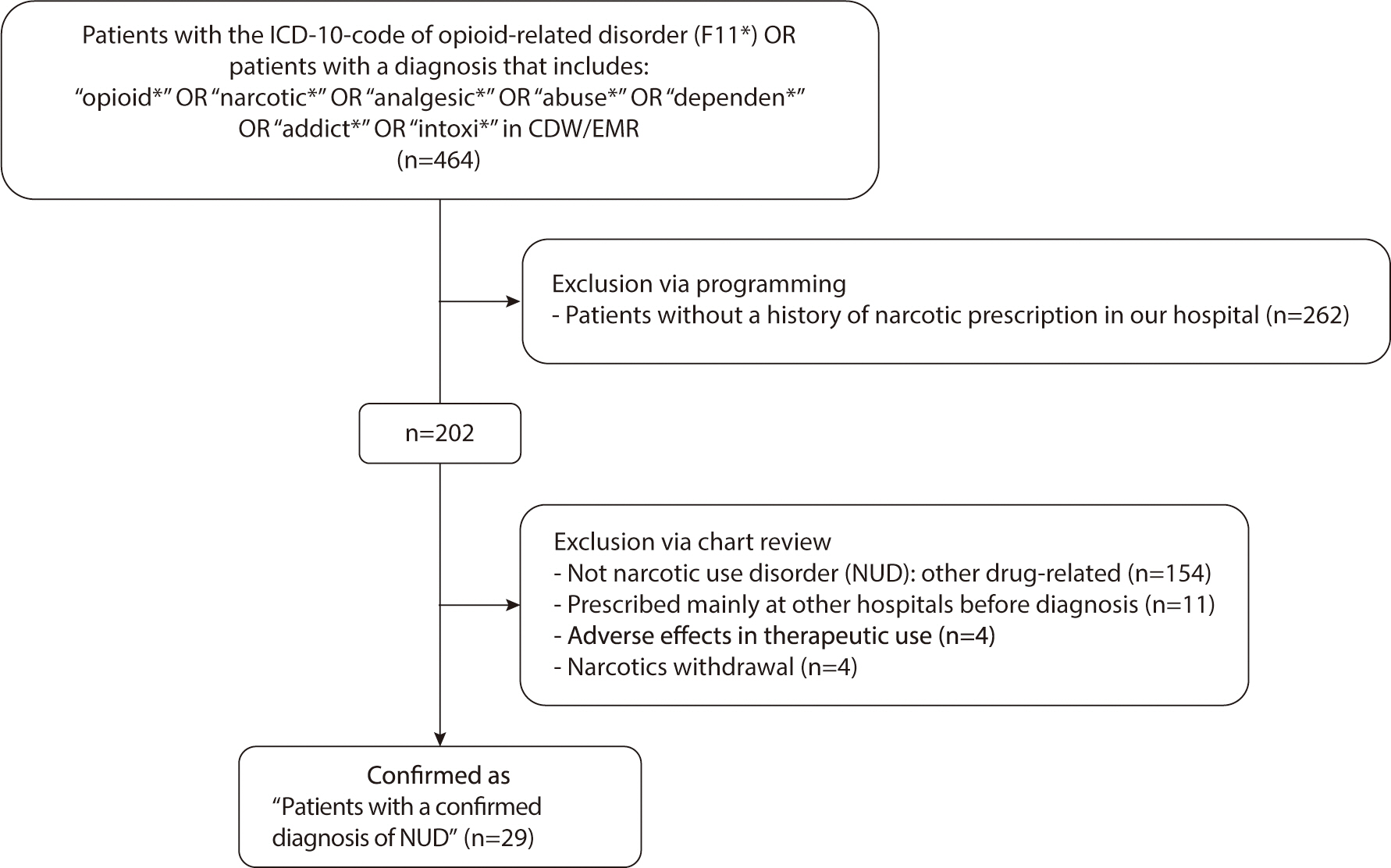

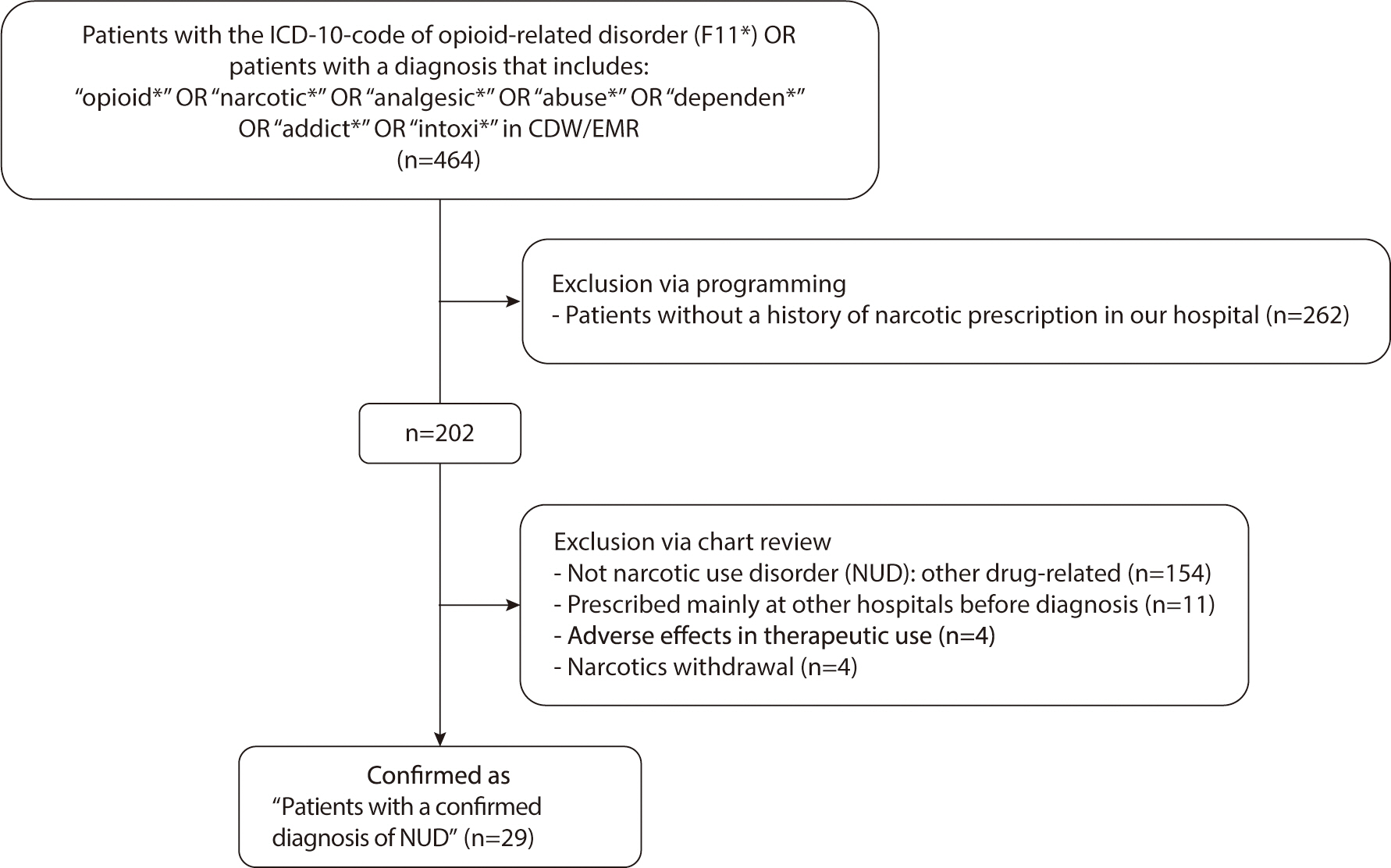

Fig. 2). Any prescriptions issued to these patients after their NUD

diagnosis were omitted from the analysis.

Fig. 2.Flowchart of patient screening and enrollment. ICD, International

Classification of Diseases; CDW, clinical data warehouse; EMR,

electronic medical records.

We also analyzed the optimal cut-off values, sensitivity, and specificity of

other high-risk NUD indexes (such as the PDMP monitoring categories) and their

combinations to confirm the effectiveness of the wt-MEDD score. To determine

whether the differences in sensitivity and specificity between the wt-MEDD score

and other indexes were statistically significant, the McNemar test was

performed.

We observed the time points at which the cut-off values of the wt-MEDD score and

other NUD high-risk indexes were reached, as well as the time points at which

NUD was diagnosed by a doctor in a patient case. This investigation aimed to

determine whether the wt-MEDD score cut-off value could be used to identify NUD

earlier. The paired t-test was employed to compare the mean time from the first

prescription of narcotics to the point of reaching the wt-MEDD score cut-off

value and the subsequent NUD diagnosis by doctors.

Participants

We analyzed the narcotic prescriptions of 221,887 patients, which were prescribed

by 8,737 doctors from July 2000 to June 2018.

Variables (study outcomes)

Considering the definition of narcotic abuse and the conditions of PDMP

monitoring, the wt-MEDD score and NUD high risk indexes (MEDD, prescription

days, prescribing frequency and duration, number of prescribing doctors, and

number of early receipt of narcotics before the scheduled visit) were selected

for analysis.

Data sources

A clinical data warehouse is a near-real-time database that consolidates data

from various clinical sources. A web-based browser facilitated the extraction of

a list of patients who met the inclusion criteria, along with their

corresponding electronic medical records. Information regarding the prescribed

patients was downloaded from the clinical data warehouse into five tables: basic

information, narcotic prescription, admission, surgery, and diagnosis

records.

Measurements

We calculated the activity of each narcotic based on its mode of

administration—tablet, patch, or injection. The table included

information on the MME conversion factor, derived from PDMP supplements [

15]. The MEDD is calculated by multiplying

the MME conversion factor by the daily dose. When MME conversion factor

information for a specific drug was not available, we estimated it from the

relevant literature [

16].

Among the five types of downloaded tables, the narcotic prescription table

included information such as the name of the prescribed drug, the date of

prescription, the number of days prescribed, and the MEDD (

Supplement 1). To

calculate the overlapping MEDD for a specific intake date, a new table was

created. This table transformed each intake date for a patient into individual

rows—not just the prescription dates—by reformatting the data from

the prescription table (

Supplement 2).

A 3-month interval was established as the measurement period for the time-series

analysis, specifically January-March, April-June, July-September, and

October-December. The total number of prescriptions issued during each 3-month

period was calculated. To analyze temporal changes in MEDD per patient, the

highest MEDD recorded in each 3-month interval was identified and compared with

the highest MEDDs from the other intervals.

Bias

All target participants were included in this study; therefore, there was no

participant bias.

Study size

Sample size estimation was not performed because this study included all target

participants.

Statistical methods

R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; URL:

http://www.R-project.org/, ver. 3.6.0) and RStudio (RStudio,

Boston, MA, USA; URL:

http://www.rstudio.com/,

ver. 1.2.1335) were used for statistical analyses. The ‘dplyr’

package in R was used to analyze data, and the ‘ggplot2’ package

was used to generate graphs. Outlier analysis was performed using the

‘outliers’ package. Cut-off value, sensitivity, specificity, and

accuracy were calculated using the ‘pROC’ package. A two-tailed

P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and doctor outliers of the weighted morphine equivalent daily dose

score

This study included 221,887 patients who received prescriptions for narcotics,

written by 8,737 doctors, totaling 555,097 narcotic prescriptions. Upon

reviewing the records of 464 patients diagnosed with NUD in the CDM, only 29

were confirmed to have NUD following repeated narcotic prescriptions at our

hospital. The majority of patients were diagnosed with NUD at other hospitals

before being transferred to our facility (

Fig.

2).

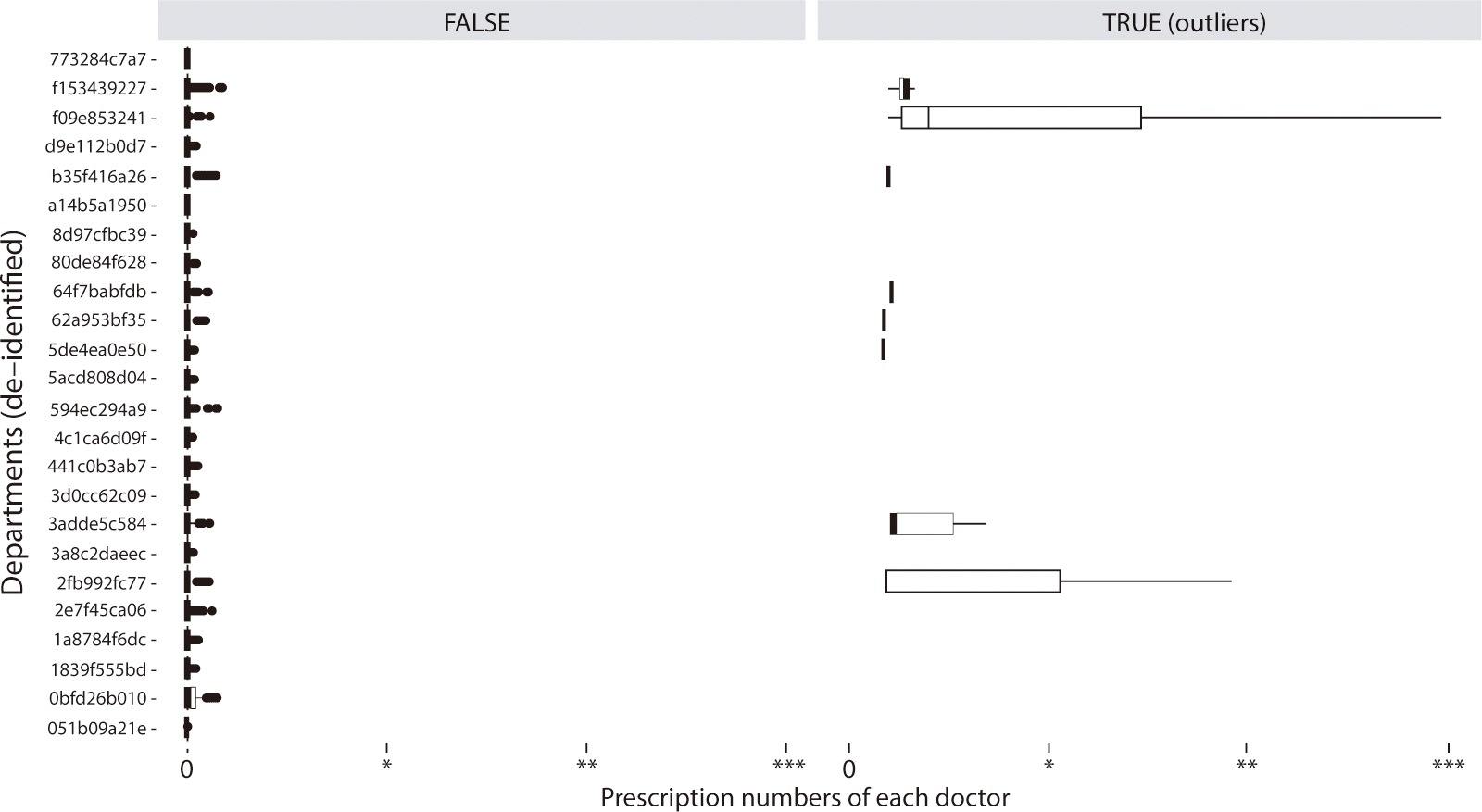

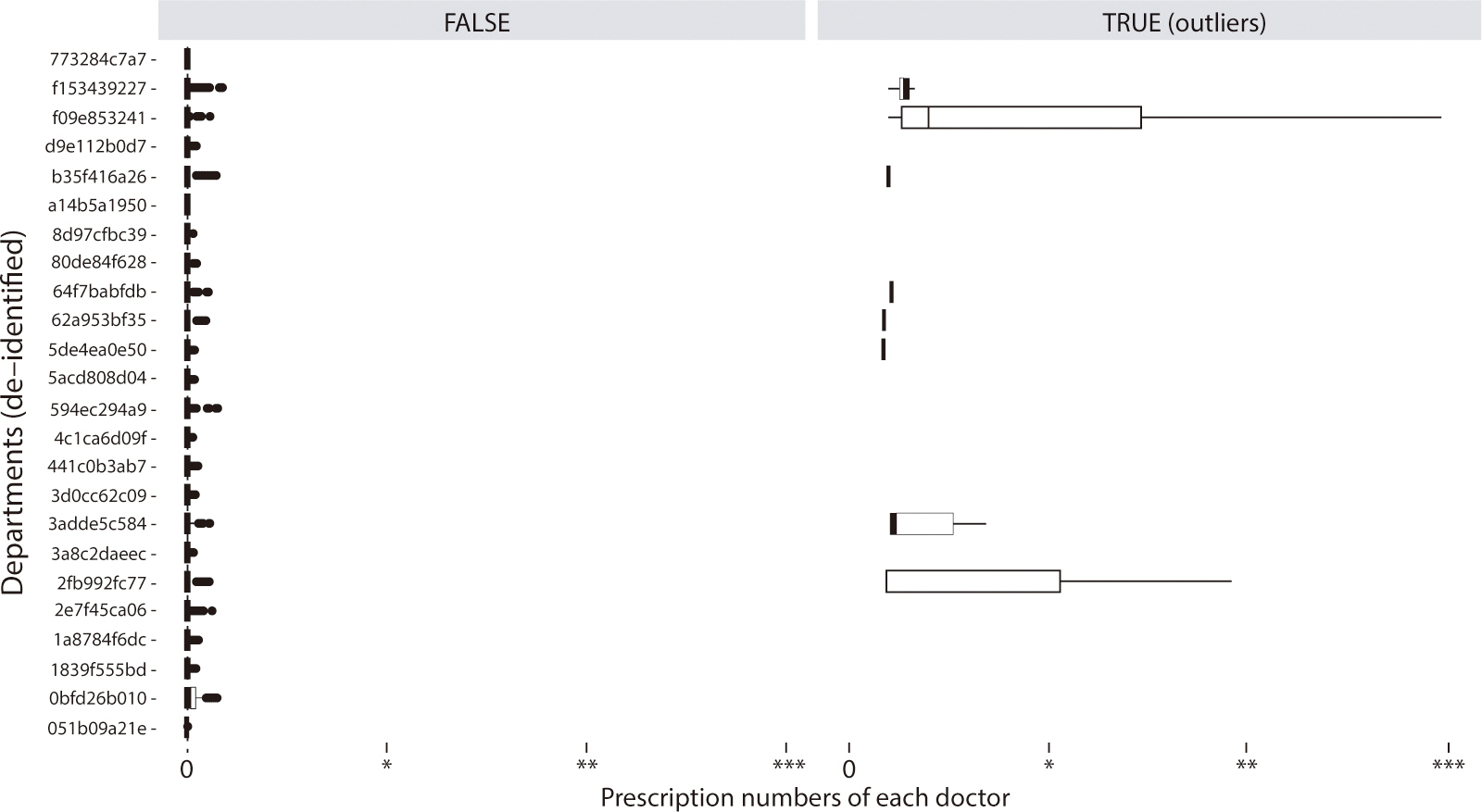

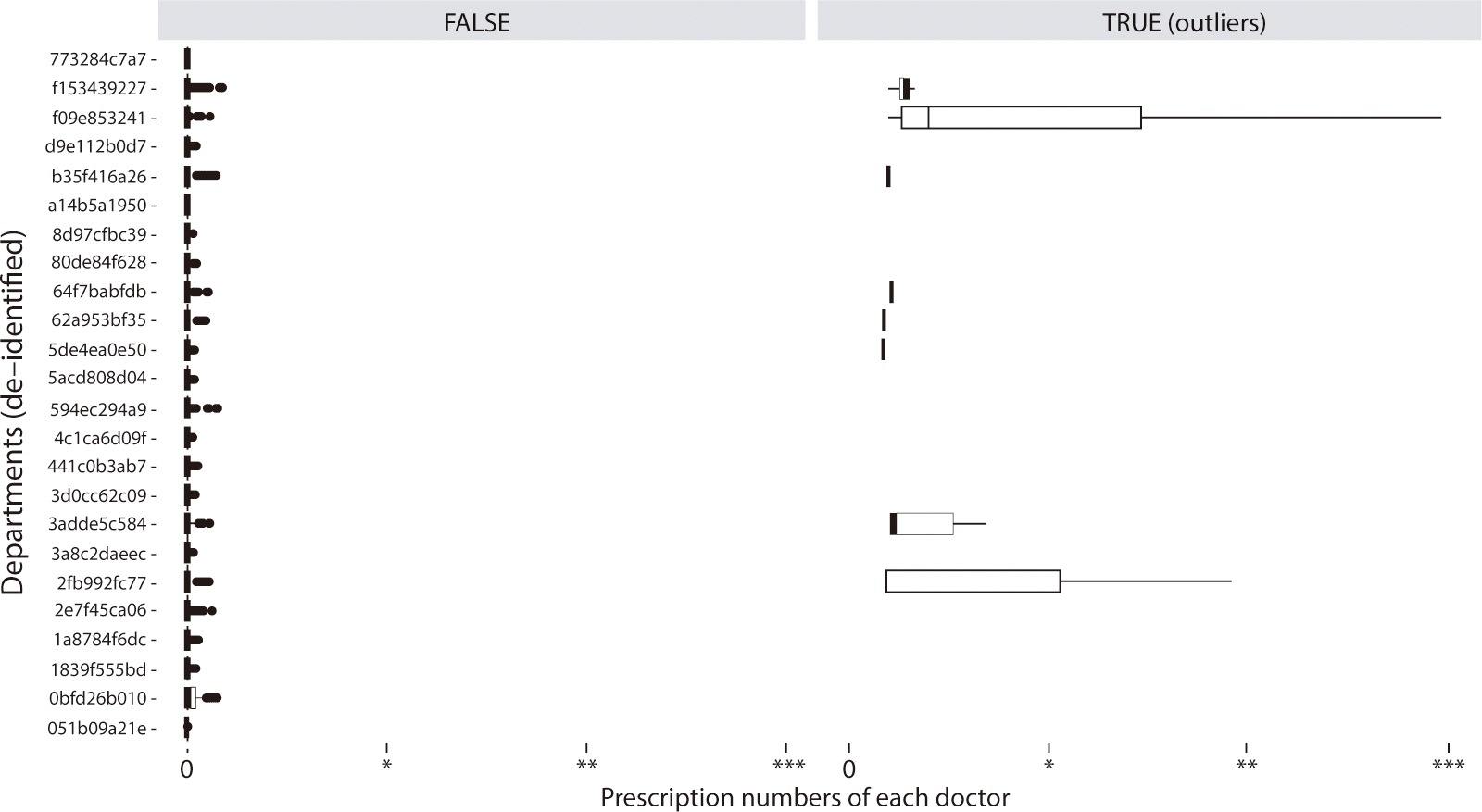

The cut-off wt-MEDD score for patient outliers (n=996) was 10.5 (P<0.001).

The list of doctor outliers (n=23) for the wt-MEDD score can be found in

Supplement 3 and

Fig. 3. This list, which included both

doctors and patients, was extracted and provided to the hospital committee to

monitor prescription abnormalities and offer feedback to the involved

doctors.

Fig. 3.Outlier doctors for the weighted morphine equivalent daily dose score

in various departments.

Comparison of the weighted morphine equivalent daily dose score and narcotic

use disorder high risk indexes in detecting diagnosed cases of narcotic use

disorder

Table 1 compares the wt-MEDD scoring

system with NUD high-risk indexes for detecting diagnosed NUD. The optimal

cut-off value for the wt-MEDD score, which demonstrated the highest sensitivity

and specificity, was ≥10.5. This value was similar to the cut-off for

outlier wt-MEDD scores (P<0.001). The median wt-MEDD score among the 29

patients diagnosed with NUD was 52 (25th–75th quartiles=25–115),

indicating that most patients with NUD had multiple prescriptions with a high

MEDD ratio, exceeding the intended prescription level. When compared to other

NUD high-risk indexes, the wt-MEDD score exhibited the highest sensitivity and

specificity (100.0% and 99.6%, respectively;

Table 1). The McNemar test revealed that the sensitivity and

specificity of the wt-MEDD score were significantly superior to those of other

indexes (P<0.001), with the exception of two indexes: the quarterly

number with a doctor number of ≥4 and the number of prescriptions

≥10 days earlier than the scheduled visit (

Table 1).

Table 1.Comparison of the performance of various indices for detecting

patients diagnosed with NUD

|

Indexes |

Cut-off |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

Accuracy (%) |

McNemar’s P-value |

|

MEDD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

wt-MEDD score (*) |

10.5 |

100.0 |

99.6 |

99.6 |

Reference |

|

Highest overlapping MEDD

(1) |

52.25 |

100.0 |

95.6 |

95.6 |

<0.001 |

|

Number of prescriptions with

intended MEDD ≥50 |

10.5 |

93.1 |

99.3 |

99.3 |

<0.001 |

|

Number of prescriptions with

intended MEDD ≥90 |

6.5 |

93.1 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

<0.001 |

|

Frequency & duration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total prescription number

(2) |

15.5 |

100.0 |

98.8 |

98.8 |

<0.001 |

|

Total number of quarter |

5.5 |

89.7 |

98.4 |

98.4 |

<0.001 |

|

Highest prescription number

per quarter1) for all prescription periods |

4.5 |

100.0 |

97.1 |

97.1 |

<0.001 |

|

Prescription day |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of prescriptions with

≥14 prescription days at once |

11.5 |

89.7 |

99.5 |

99.5 |

<0.001 |

|

≥30 days at once

(3) |

0.5 |

62.1 |

98.3 |

98.3 |

<0.001 |

|

≥60 days at once |

1.5 |

27.6 |

99.7 |

99.7 |

<0.001 |

|

≥90 days at once |

3.5 |

13.8 |

100.0 |

99.9 |

<0.001 |

|

Number of doctors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total number of doctors

(4) |

6.5 |

96.6 |

98.7 |

98.7 |

<0.001 |

|

Quarterly number with doctor

number of ≥4 |

0.5 |

93.1 |

98.3 |

98.3 |

0.107 |

|

Highest number of doctors per

quarter1) for all prescription periods |

2.5 |

96.6 |

96.3 |

96.3 |

<0.001 |

|

Early prescription |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of prescriptions

≥1 day earlier than the scheduled visit |

1.5 |

93.1 |

99.1 |

99.1 |

<0.001 |

|

≥2 days earlier |

0.5 |

89.7 |

98.6 |

98.6 |

<0.001 |

|

≥3 days earlier |

0.5 |

89.7 |

98.8 |

98.8 |

<0.001 |

|

≥4 days earlier |

1.5 |

86.2 |

99.5 |

99.5 |

<0.001 |

|

≥5 days earlier |

1.5 |

86.2 |

99.5 |

99.5 |

<0.001 |

|

≥6 days earlier |

1.5 |

86.2 |

99.6 |

99.6 |

<0.001 |

|

≥7 days earlier

(5) |

0.5 |

86.2 |

99.1 |

99.1 |

<0.001 |

|

≥10 days earlier |

1.5 |

82.8 |

99.7 |

99.7 |

0.548 |

|

≥14 days earlier |

0.5 |

82.8 |

99.5 |

99.5 |

<0.001 |

|

Combination of methods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (4)

(triple-test) |

|

96.6 |

99.5 |

99.5 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (4) |

|

58.6 |

99.8 |

99.8 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (5) |

|

82.8 |

99.8 |

99.8 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (4) ∩ (5) |

|

58.6 |

99.9 |

99.9 |

<0.001 |

|

((1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (4)) ∪ ((1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3) ∩

(5)) |

|

82.8 |

99.8 |

99.8 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (4)

∩ (*) |

|

96.6 |

99.7 |

99.7 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (4) ∩ (*) |

|

58.6 |

99.9 |

99.9 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (5) ∩ (*) |

|

82.8 |

99.8 |

99.8 |

<0.001 |

|

(1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (4) ∩ (5) ∩ (*) |

|

58.6 |

99.9 |

99.9 |

<0.001 |

|

(((1) ∩ (2) ∩

(3) ∩ (4)) ∪ ((1) ∩ (2) ∩ (3)

∩ (5))) ∩ (*) |

|

82.8 |

99.8 |

99.8 |

<0.001 |

To improve the ability to detect NUD, we combined the NUD high-risk indexes with

the wt-MEDD score and assessed their sensitivity and specificity. A combined

model that included the highest overlapping MEDD, total number of prescriptions,

and total number of doctors (triple-test) demonstrated excellent sensitivity and

specificity, at 96.6% and 99.5% respectively. When the wt-MEDD score was used in

conjunction with the triple-test, the sensitivity and specificity further

improved to 96.6% and 99.7%, respectively. These results suggest that the

wt-MEDD score, when combined with other NUD high-risk indexes, is effective for

screening patients with NUD (

Table

1).

In all 29 patients diagnosed with NUD, the time point at which the wt-MEDD

cut-off score was reached occurred earlier than the time point of the

doctor's initial diagnosis of NUD. The average time to reach the wt-MEDD

cut-off score was 1,024 days (median [quartile 1–quartile 3], 361

[192–2,323]) from the first narcotics prescription. In contrast, the

average time until NUD diagnosis was 2,578 days (median [quartile

1–quartile 3], 2,342 [1,396–4,030]). This resulted in an average

difference of 1,554 days (95% CI, 1,096–2,010 days, paired t-test,

P<0.001).

Patient case report

To provide an example of the clinical application of the new methodology (wt-MEDD

score) in identifying cases of NUD, we selected a patient diagnosed with NUD who

employed multiple strategies to obtain a higher number of narcotics

prescriptions. We retrospectively observed the time-sequential changes in the

wt-MEDD score and the NUD high-risk indexes for this patient up until the NUD

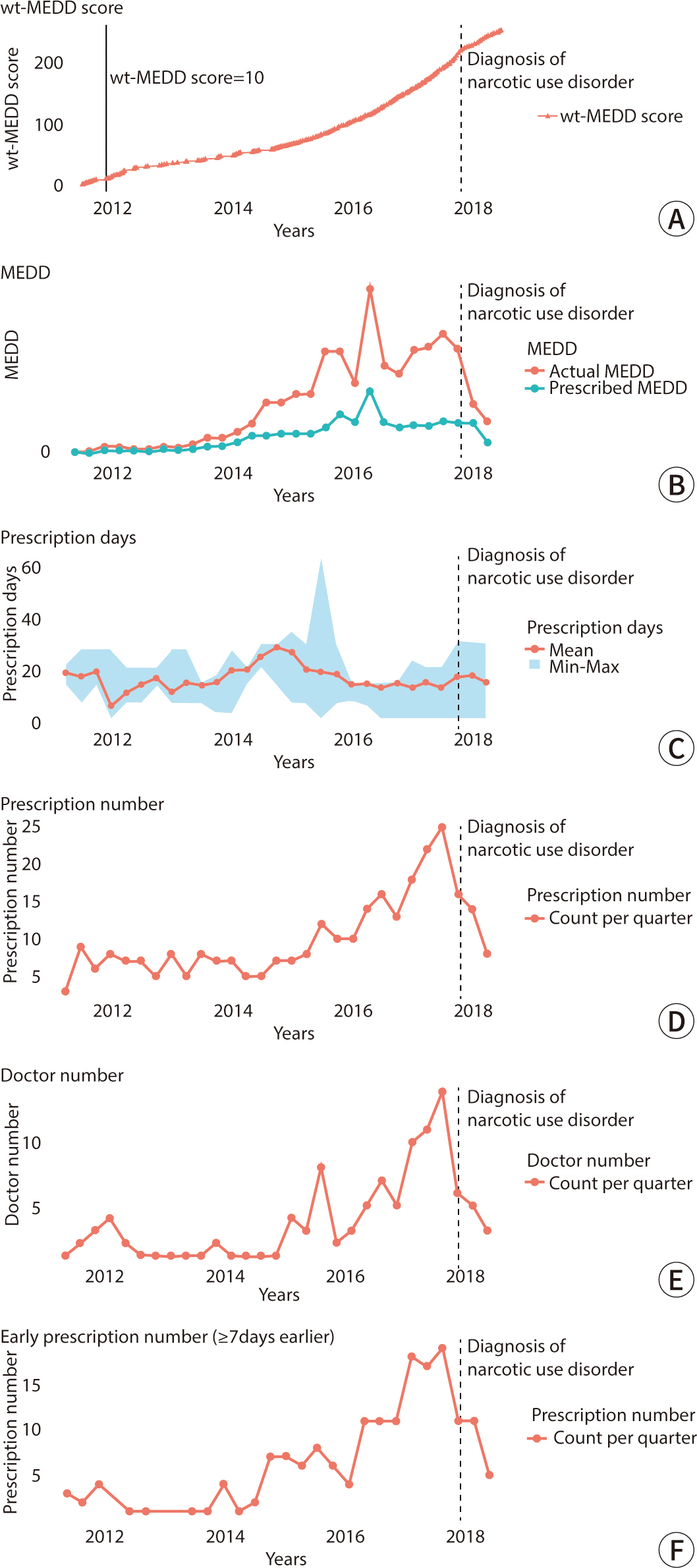

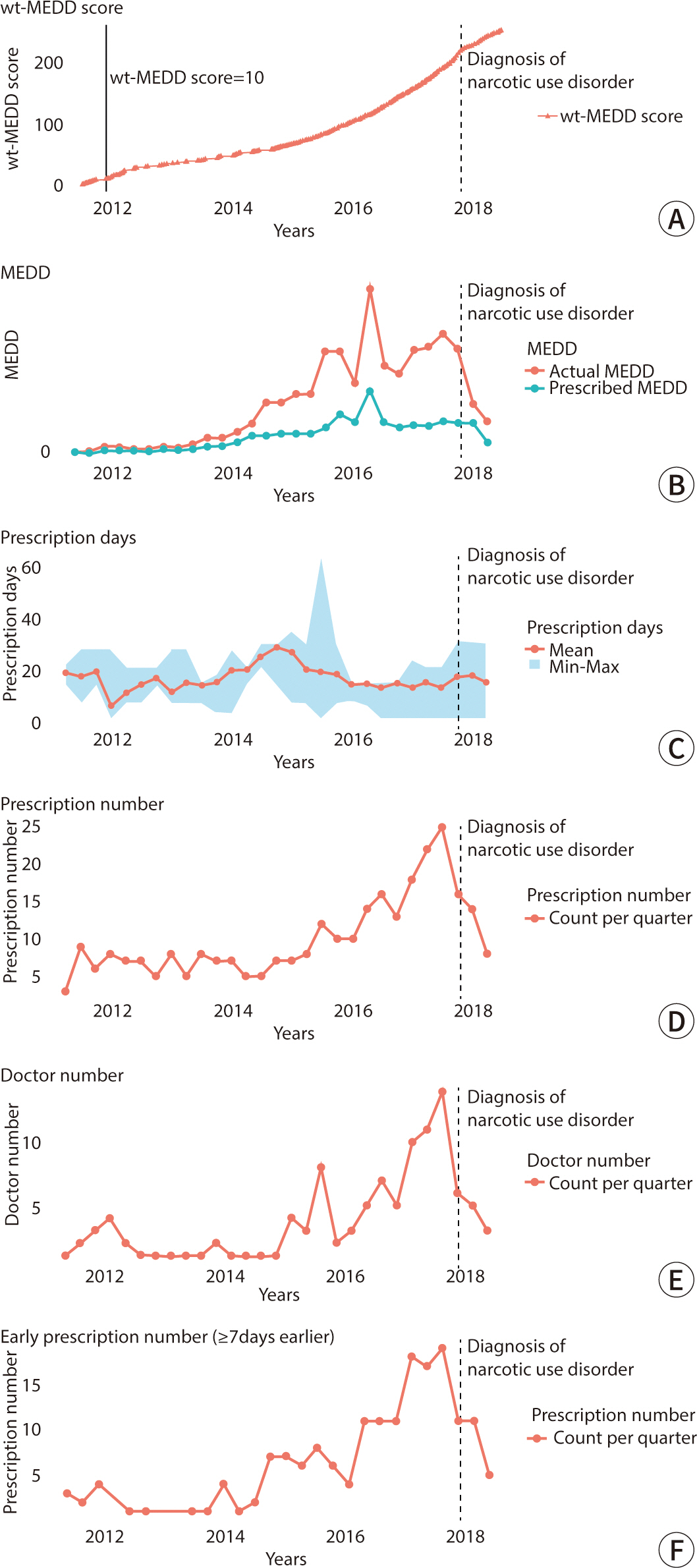

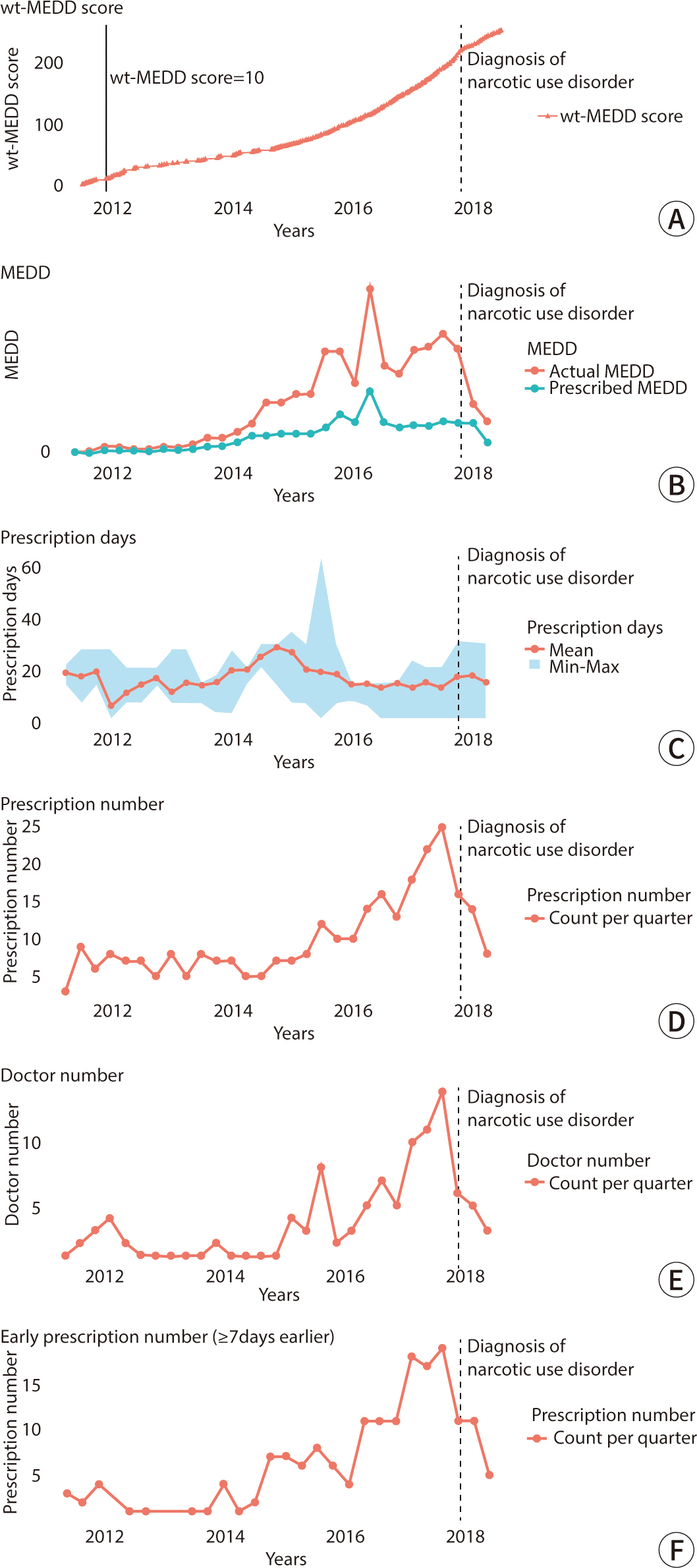

diagnosis was made (

Fig. 4).

Fig. 4A demonstrates a gradual increase in

the patient's wt-MEDD score over time. Initially, the score was 10 in

November 2011, and the patient received a diagnosis of NUD in October 2017. If

the wt-MEDD score had been utilized as a screening tool for this patient, it

could have potentially led to a diagnosis of NUD 6 years earlier.

Fig. 4.Temporal changes in various NUD high risk indices for patients

diagnosed with NUD. (A) wt-MEDD, (B) highest actual and intended MEDD

every 3 months, (C) highest prescription days every 3 months, (D) total

number of prescriptions every 3 months, (E) total number of prescribing

doctors every 3 months, (F) number of early receipt of narcotics before

≥7 days for every 3 months. MEDD, morphine equivalent; wt-MEDD,

weighted MEDD; NUD, narcotic use disorder.

The difference between the actual MEDD and the intended MEDD (MEDD ratio)

continued to increase until the diagnosis of NUD was made (

Fig. 4B). Concurrently, the number of prescription days

(mean, minimum, and maximum) showed an increase just prior to the rise in the

MEDD ratio (

Fig. 4C). Similarly, the

patterns of increase in the number of prescriptions (

Fig. 4D), the number of prescribing doctors per 3-month

period (

Fig. 4E), and the instances of

early receipt of narcotics for more than 7 days (

Fig. 4F) mirrored the trend observed in the MEDD ratio. These

findings suggest that employing multiple strategies can elevate the MEDD ratio,

potentially leading to a diagnosis of NUD. Despite the use of various strategies

to obtain more narcotics, it is possible to effectively screen for NUD at an

early prescription stage using only the wt-MEDD score, without the need for

multiple indicators.

Discussion

Key results

The wt-MEDD score demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in identifying early

patterns of narcotic prescriptions in patients who were later diagnosed with

NUD. This score reflects the number of prescription dates with a high MEDD

ratio. A wt-MEDD score greater than 10.5 marked patients as significant

outliers, aligning with the optimal cut-off value used by physicians to detect

NUD. With a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 99.6%, a wt-MEDD score of

10.5 proved highly effective in identifying patients diagnosed with NUD. These

results indicate that a wt-MEDD score of 10.5 could serve as a screening tool to

detect patients with NUD, particularly those engaging in behaviors like

"doctor shopping" to obtain excessive amounts of narcotics.

Interpretation

Our hospital undertook an analysis of abnormal patterns in narcotic prescriptions

to prevent NUD in patients by providing feedback to prescribing doctors.

Initially, we consulted the CDC guideline [

7], which proved both reasonable and useful, as evidenced by its

alignment with the optimal cut-off values identified in our study for detecting

patients with NUD. However, adherence to the CDC guideline alone was

insufficient for categorizing a patient with NUD. To provide prescribing doctors

with clearer information reflective of NUD, we took into account scenarios that

could be problematic without exception. For instance, a patient receiving high

doses of narcotics inconsistent with the prescribing doctor's intentions

was identified as a problematic situation and thus was considered appropriate

for defining NUD.

In the United States, the PDMP system automatically calculates the MEDD for

prescribed narcotics. It provides the total MEDD for multiple prescriptions on

the date they are issued; however, it does not calculate the overlapping MEDD

that results from multiple prescriptions on a specific intake date [

17]. Although the Ohio Automated Rx

Reporting System displays daily MME for prescribers, this information is not

stored, making it challenging to reconstruct later [

17]. Previous studies have examined overlapping

prescriptions, focusing either on concurrent benzodiazepine and narcotic

prescriptions [

18] or on overlapping

prescriptions without considering the overlapping MEDD [

19]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate

the wt-MEDD score, which is based on the number of days with a high MEDD ratio,

as a tool for identifying abnormal prescription patterns.

The wt-MEDD score is effective in identifying abnormal prescriptions,

irrespective of the methods patients employ to obtain more narcotics.

Additionally, a graph depicting the MEDD ratio over time can be made available

for each patient in the outpatient clinic. The capability to quickly observe

temporal changes through the graph can significantly reduce the time required to

detect unusual prescription patterns.

An opioid-risk tool, previously reported and based on fixed patient

characteristics such as a history of alcoholism, has been shown to have a

primary prevention effect on NUD [

20].

However, it does not contribute to secondary prevention. In contrast, monitoring

the wt-MEDD score facilitates screening prior to an increase in the number of

abnormal prescriptions.

Calculating the wt-MEDD score based on overlapping MEDD could lead to an increase

in data volume, as each intake date—rather than just the prescription

date—adds an additional row to the table. In our study, the data size for

tables based on each intake date was five times larger than those based on each

prescription date. However, limiting the analysis to patients who have been

prescribed narcotics, rather than including all hospital patients, could

alleviate the burden of data analysis. Additionally, our study only included a

small number of patients diagnosed with NUD, possibly due to physicians'

reluctance to diagnose NUD. This issue is particularly acute for patients who

have received narcotics prescriptions from more than one department, where

cross-departmental liability issues may complicate the diagnosis of NUD.

Consequently, there could be a larger number of undiagnosed NUD cases,

especially among those categorized as wt-MEDD outliers. Moreover, our analysis

did not include narcotic prescriptions for cancer patients, inpatients, or those

receiving relatively low doses of narcotics such as codeine and tramadol. These

groups are expected to be analyzed using different criteria. This study was

retrospective, suggesting that a prospective trial might be necessary to

determine if monitoring the wt-MEDD score can reduce the incidence of NUD.

Additionally, since our study population was limited to a single hospital, it

did not account for narcotics prescribed to patients at other facilities. Given

that patients with NUD are likely to receive narcotics prescriptions from

multiple hospitals, an integrated system to monitor narcotic prescriptions

nationwide becomes essential. In the United States, for example, the PDMP

manages all narcotic prescriptions at the state level [

21]. However, the variation in narcotic policies between

different hospitals and countries could complicate such analysis [

22]. Nonetheless, if the system can

effectively detect NUD through hospital prescriptions, a method for confirming

the wt-MEDD score might prove universally beneficial.

We defined the wt-MEDD score as the number of prescription days with a high MEDD

ratio, based on the definition of narcotic abuse. The wt-MEDD score identified

patients diagnosed with NUD with greater sensitivity and specificity than other

metrics. Therefore, monitoring the wt-MEDD score could enable early

interventions for irregular narcotics prescription patterns by doctors and help

prevent the development of NUD in patients.

Authors' contributions

-

Project administration: Kim YJ

Conceptualization: Kim YJ

Methodology & data curation: Kim YJ, Lee KH

Funding acquisition: Kim YJ

Writing – original draft: Kim YJ

Writing – review & editing: Kim YJ, Lee KH

Conflict of interest

-

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

-

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through a

National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of

Science and ICT (No. RS-2023-00213119, No. RS-2024-00440273), and the Korea

Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry

Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health &

Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. HR21C0198, No. HI21C1218).

Data availability

-

Research data and R code is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Please contact them for collaborative studies.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Supplementary materials

-

Supplementary materials are available from: https://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2024.e63.

Supplement 1. Structure of a part of the narcotic prescription table

Supplement 2. Structure of a part of the modified narcotics prescription table

according to each intake date to calculate overlapping MEDD

Supplement 3. Partial list of doctor outliers of the wt-MEDD score

References

- 1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]. Executive summary: conclusions and policy implications. New York: United Nations; 2018.

- 2. Sproule B, Brands B, Li S, Catz-Biro L. Changing patterns in opioid addiction: characterizing users of

oxycodone and other opioids. Can Fam Physician 2009;55(1):68-69.e5.

- 3. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a

systematic review and data synthesis. PAIN 2015;156(4):569-576.

- 4. Califf RM, Woodcock J, Ostroff S. A proactive response to prescription opioid abuse. N Engl J Med 2016;374(15):1480-1485.

- 5. Cochran G, Woo B, Lo-Ciganic WH, Gordon AJ, Donohue JM, Gellad WF. Defining nonmedical use of prescription opioids within health

care claims: a systematic review. Subst Abuse 2015;36(2):192-202.

- 6. Saunders JB. Substance use and addictive disorders in DSM-5 and ICD 10 and the

draft ICD 11. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017;30(4):227-237.

- 7. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: United

States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315(15):1624-1645.

- 8. Haffajee RL, Jena AB, Weiner SG. Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring

programs. JAMA 2015;313(9):891-892.

- 9. Delcher C, Wagenaar AC, Goldberger BA, Cook RL, Maldonado-Molina MM. Abrupt decline in oxycodone-caused mortality after implementation

of Florida's Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;150:63-68.

- 10. Pardo B. Do more robust prescription drug monitoring programs reduce

prescription opioid overdose? Addiction 2017;112(10):1773-1783.

- 11. Fink DS, Schleimer JP, Sarvet A, Grover KK, Delcher C, Castillo-Carniglia A, et al. Association between prescription drug monitoring programs and

nonfatal and fatal drug overdoses: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2018;168(11):783-790.

- 12. Häuser W, Schug S, Furlan AD. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy

for chronic noncancer pain: a perspective from different

continents. PAIN Rep 2017;2(3):599.

- 13. Kaye AD, Jones MR, Kaye AM, Ripoll JG, Galan V, Beakley BD, et al. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: an updated review of

opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse: part

1. Pain Physician 2017;20(2S):S93-S109.

- 14. White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Tang J, Katz NP. Analytic models to identify patients at risk for prescription

opioid abuse. Am J Manag Care 2009;15(12):897-906.

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data resources: data files of select controlled substances including

opioids with oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors,

2018 version [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; c2018 [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/document/opioid-oral-morphine-milligram-equivalent-mme-conversion-factors-0

- 16. Reddy A, Vidal M, Stephen S, Baumgartner K, Dost S, Nguyen A, et al. The conversion ratio from intravenous hydromorphone to oral

opioids in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 2017;54(3):280-288.

- 17. Winstanley EL, Zhang Y, Mashni R, Schnee S, Penm J, Boone J, et al. Mandatory review of a prescription drug monitoring program and

impact on opioid and benzodiazepine dispensing. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;188:169-174.

- 18. Hwang CS, Kang EM, Kornegay CJ, Staffa JA, Jones CM, McAninch JK. Trends in the concomitant prescribing of opioids and

benzodiazepines, 2002–2014. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(2):151-160.

- 19. Yang Z, Wilsey B, Bohm M, Weyrich M, Roy K, Ritley D, et al. Defining risk of prescription opioid overdose: pharmacy shopping

and overlapping prescriptions among long-term opioid users in

medicaid. J Pain 2015;16(5):445-453.

- 20. Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients:

preliminary validation of the opioid risk tool. Pain Med 2005;6(6):432-442.

- 21. Wen H, Schackman BR, Aden B, Bao Y. States with prescription drug monitoring mandates saw a reduction

in opioids prescribed to Medicaid enrollees. Health Aff 2017;36(4):733-741.

- 22. Helmerhorst GTT, Teunis T, Janssen SJ, Ring D. An epidemic of the use, misuse and overdose of opioids and deaths

due to overdose, in the United States and Canada: is Europe

next? Bone Joint J 2017;99(7):856-864.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by